In the Late 1960s, Singapore Was Gripped by a Genital Panic

Of all the national panics, this might be the most bizarre.

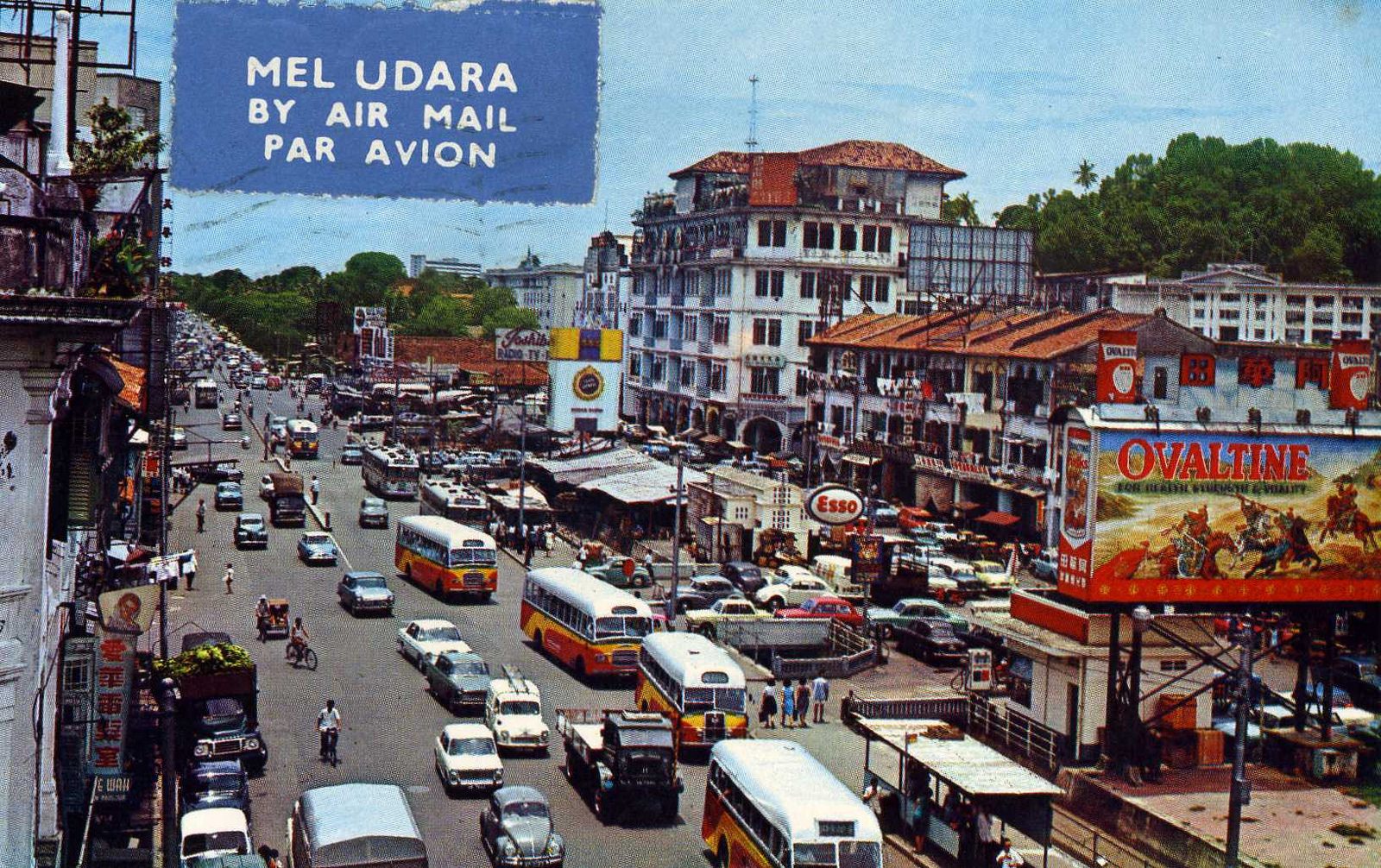

At the very end of the Malay peninsula sits the city state of Singapore, which was once plagued with retracting penises. In 1967, in one of the best-documented epidemics of koro, (or genital retraction syndrome) ever, hundreds of people rushed to hospitals, deathly afraid that if they loosened their grip they would die.

Today Singapore is one of the wealthiest and most successful countries on earth, and much of its old character seems to have been washed away by a tide of modernization. An international crossroads for hundreds of years, the city is now clean and safe and has everything most countries aspire to. You can walk along the street and be sure none of your body parts will disappear. But this wasn’t always the case.

The mass genital shrinking epidemic began in October of 1967. In one case, a 16-year-old male rushed into the General Hospital’s outdoor clinic with his parents close behind. “The boy looked frightened and pale,” as one report described it, “and he was pulling hard on his penis to prevent the organ from disappearing into his abdomen.”

The boy’s parents shouted for the doctors to help because the boy had suo yang (the Chinese word for koro, which we consider a culturally-related “genital retraction syndrome”) and if the retraction didn’t stop, he would die. The doctors reassured the family and gave the boy ten milligrams of chlordiazepoxide, after which he improved.

The boy’s problem had started at school, where he’d heard rumors that tainted pork—inoculated against swine fever—could cause koro. Earlier that morning, he’d eaten a steamed bun with pork in it. When he went to urinate, he looked down and felt his penis start to shrink. “Frightened, he quickly grasped the organ and rushed to his parents shouting for help.”

More people followed. Before long the hospitals were flooded with patients. Pork sales plummeted. The Ministry of Primary Production announced that both swine fever and the vaccine were harmless to humans, but the epidemic seemed to accelerate. For seven days it continued, until finally the Singapore Medical Association and the Ministry of Health started appearing on television and radio to announce that suo yang was a purely psychological condition, and that no one had died from it. There was an immediate drop in the number of cases. By November, there were no reports at all.

In the end, a total of 469 cases were recorded, though the real number was certainly higher, since the survey only included Western hospitals and did not account for traditional Chinese doctors. All patients who were interviewed by doctors had heard stories about koro before they experienced it. After the epidemic, the Chinese Physician Association concluded that “the epidemic of Shook Yang was due to fear, rumor mongering, climatic conditions, and imbalance between heart and kidneys….” Meanwhile, a Western-oriented “Koro Study Team,” concluded that koro was “a panic syndrome linked with cultural indoctrination.”

How much had changed since 1967? Had the remains of the city’s old culture been washed away in the tide of modernization? Were the old ways of thinking—of believing—gone? Or was it more complicated?

Singapore’s Chinatown is peppered with stores that sell traditional Chinese medicine. Not long after I arrived in the city, I went there to ask around about suo yang and strolled among the open bins of flattened squid, dried sea cucumbers, mushrooms, oysters, and tree bark. People streamed in constantly, bringing their health complaints, for which the shopkeepers could prescribe a mix of herbs and other ingredients—either fresh or prepackaged. The stores did a brisk business.

In one shop in a dingy open-air mall packed with travel agencies, photocopy shops, noodle stands, and tea stores, I approached the counter. A portly man behind it ambled over. For some reason, I had my hand on stomach. He pointed to it.

“You have problem with bathroom?”

His English was choppy, but he made a downward sweep with his hand that indicated the flushing of the bowels.

“Yes,” I said. This was sort of true.

“You go every day?”

“Yes.”

“Too many per day?”

I just kept saying yes. It seemed easier than launching into my genital inquiry. He brought over a small box.

“You take this every day.”

“Is this for yin or yang?”

“Oh you know yin and yang!”

“A little.”

“This for too much yin.”

“Do you have anyone with suo yang?”

He stared blankly.

“Suo yang?” I said again. “When the man’s penis is being sucked into his body?”

“No, never.”

“Were you here in 1967?”

“In 1967, I study.”

I bought the stomach medicine, then walked around till I came to another shop. I asked the man working if he knew suo yang. “You know, when your penis is disappearing into your body.” I tried to make the motions, but it was a strange public game of charades. He pointed to his crotch. “You mean for this problem?”

“Yes.”

“For men?”

“Yes.”

He handed me a box of small pills. “This very good,” he said. He turned away from the female clerks, lowered his elbow to his crotch and raised his forearm like a giant erection. “Makes you very strong.”

“Thank you,” I said, and I took the box from him an examined the label. This was not working. Language was a problem.

I put the medicine back, then went and called a friend who lived in the city, and who spoke and wrote Mandarin. He e-mailed me the Chinese characters for suo yang along with an explanation. I printed these out, then went back to Chinatown and stopped into the first shop I came to. I showed the woman at the country the paper.

“Do you know this?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “One of the ingredients is suo yang. It’s especially for men.

“No,” I said, “it’s not an ingredient. It’s a condition. There was an epidemic and people thought they were going to die.”

She looked at the paper. “To die? For this problem, maybe you should see the doctor.”

“The traditional doctor?”

“Yes, he will be back in half an hour.”

“But I don’t need the medicine for myself.”

“Here’s some medicine. This will help you.” She handed me a small box.

“How much is this?”

“Twenty dollars.”

Back on the streets, I walked past the Chinatown museum, past the crowd of tourists looking at drink menus. Despite appearances, and despite my communication troubles, it was clear that people had not stopped believing in the world as it was stitched together in old Chinese medical texts. Perhaps the difference was simply that now there was another world, the Western one, layered on top in a kind of palimpsest. How did they fit together? Was the older one weaker than before?

Before I left, I stopped in one last shop. The man working there wasn’t particularly old but he spoke good English, so I asked him directly: “Do you ever have people ask about suo yang? When the penis is disappearing into the body?”

He knew exactly what I meant.

“For that,” he said, “you need tiger penis. But it’s very hard to get in Singapore. Maybe you go to Thailand.”

“But do you get many people asking about it?”

“Not now. In the olden days, yes. But now, no.”

“What would you do for them?”

“For that,” he said, “you need to see your physician.”

A version of this story appeared in the author’s book, The Geography of Madness: Penis Thieves, Voodoo Death, and the Search for the Meaning of the World’s Strangest Syndromes.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook