India and Nepal’s Mithila Art Is Having a Feminist Renaissance

As the region changes apace, so does an ancient style of painting.

The Mithila region of southern Nepal and northern India lies in the flatlands that join the two countries, blanketed by sugarcane fields and golden meadows. Politically divided by a border, it is united by culture, history, and the Maithili language.

On Nepal’s side lies Janakpur, an ancient city considered the birthplace of the Hindu goddess Sita. Today, locals in this once sprawling kingdom browse for iPhones in shops that line narrow roads, or nap on the concrete banks of the city’s sacred ponds. Hindus travel to Janakpur to pray at the Janaki Mandir, a white marble temple that illuminates the city center.

Unknown to most visitors, the temple also houses a women’s art studio that’s covered in vivid Mithila paintings—an ancient art form defined by colorful geometric shapes and lines. On a recent afternoon, Sunaina Thakur, a local artist who runs the studio, sat inside under the whir of a clicking fan, watching a painter she’s been training steady her hand over a silk cloth and dab it with black paint. The image the painter was creating showed a bride being carried to the home of her groom.

A group of other female artists sat nearby, leaning on one another. Malti Paswan, dressed in a red and yellow sari, fixed her eyes on the painter’s strokes. The scene being rendered was a familiar one in Mithila art, romantic and classic—one that sells easily to Hindu pilgrims who amble into the shop.

Paswan and the other artists here grew up observing their mothers paint Mithila at home. Their mothers had learned it from their mothers, and so on. For centuries—some say thousands of years—women in the Mithila region have practiced this art form, painting expressions of their faith and desires.

In recent years, however, they’ve started addressing contemporary feminist issues and their visions of equality in this rapidly changing region.

Paswan says she’s been brainstorming ideas for a new series of her own—something more personal. One painting will show a woman standing before a male relative, peering at him through her scarf. Called purdah, it is an abiding practice in parts of South Asia and elsewhere in which women are expected to conceal their faces in front of male relatives or strangers, or to stay secluded in their homes. It is considered respectful by many. But it’s a practice that some local women have been quietly defying for years.

“I want to show people my sorrow—the sorrow I felt doing these things,” Paswan says. “I want people to know what it felt like.”

Many believe that Mithila art traces back to the time of the Sanskrit epic Ramayana, when King Janaka, the ruler of the region, is said to have recruited local artists to paint his daughter Sita’s marriage to Rama. For generations, women painted the mud walls of their houses with images of Hindu deities, animals, and nature—a tradition that lasted for centuries and has only recently faded as families have begun building their houses with concrete. Originally painted using red and black natural dyes, these colorful pieces are now completed on canvas, usually with synthetic paint, and practiced by artists across caste and class backgrounds

Little else is known about its history, but local texts began referencing Mithila as early as the 14th century. Hundreds of years later, when a drought devastated the region, in the late 1960s, India’s government encouraged locals to paint their work on canvas and sell it as a means of income generation.

Once practiced only in the private sphere, Mithila painting suddenly became a profession, ushering in new opportunities for local women. By the 1970s, artists were selling their paintings to dealers who would resell them in craft markets in big cities. But they often asked artists to produce dozens of the same painting, for meager pay—a practice that continues today.

Concerned by what he saw, Raymond Owens, an American anthropologist in Bihar at the time, bought Mithila paintings at a high price, sold and exhibited them in the United States, then gave the profits back to the artists.

Owens later established the Ethnic Arts Foundation, an organization that exhibits and supports research on Mithila art and has helped train over 400 artists in Bihar through the Mithila Art Institute. In Nepal, one of the first places to train women to sell Mithila art professionally was the Janakpur Women’s Development Center, founded in the late 1980s. Today a number of other training centers dot the Mithila region.

Most contemporary Mithila artists sell their paintings to tourists in craft and fair-trade shops, usually for a few hundred or thousand rupees. Some of these artists have gained national and international attention, exhibiting their paintings in galleries and museums across South Asia, Europe, the United States, and Japan. Prices vary, but these pieces typically sell for several hundred U.S. dollars (though a few have fetched as much as several thousand).

Inside the studio in Janakpur, where temple chants and Hindi music vibrate through the room, the artists talk about gender issues in the region. Maithili society is considered severely patriarchal. Across Nepal, more girls have enrolled in primary school since 1990. But many eventually drop out due to housework responsibilities, early marriage, and other factors. Nationally, 80 percent of girls drop out by 11th grade.

“The next generation has it better [than] ours [did],” Thakur says. She pauses, then explains that many rural women still face social strictures and may be gossiped about if they talk to strangers or people who aren’t their relatives or neighbors.

Paswan looks up and smiles. “We’ve come here today, but people are going to talk about where we went,” she says. She starts whimpering. “Oh, they went with Sunaina! What are they up to?’” The women burst out laughing.

Married at 16, Thakur left school prematurely and moved into her husband’s home, in order to raise their son and take care of her in-laws. Like other women here, she grew up painting Mithila art. So years later, she asked some local artists to teach her techniques. In 2008, she started training other women herself.

The pushback Thakur faced was intense, but short-lived. At the time, few women in her area were selling Mithila pieces professionally or working outside their homes. Husbands barred their wives from meeting with Thakur. One of them called the group “men” for going out to work, then added that they “still have to go home and go to the kitchen.”

The criticism vanished once the women began earning real income from their paintings, by selling them in craft stores in Janakpur and Kathmandu. Painters at the Janakpur Women’s Development Center had faced similar resistance in the 1990s. But as more social and economic development came to the region, selling Mithila became normalized, according to the center’s founder, Claire Burkert.

Thakur is known for painting feminist themes, depicting local women holding traditionally male jobs—police officer, pilot, and so on. But she also paints women in household roles, doing unpaid care work that sustains families and economies. She points at one painting, a collage that shows women preparing for Hindu festivals—Chhath Puja, Tihar, and Holi—in the Mithila region. “[These women’s work] should be valued,” she says. “But it’s not.”

Distinctly feminist themes are a relatively new phenomenon in Mithila art. Lina Vincent Sunish, an art historian and curator based in India, says that Mithila artists started explicitly addressing gender issues in the early 2000s, many of them inspired by their discussions with teachers at the Mithila Art Institute.

But Sunish believes that long before that, some Mithila artists were using mythological scenes to hint at something more personal. She cites an old painting that depicted Sita—her eyes open wide with fury.

“The stance. The gaze. The gestures,” she says. “It’s there. It’s there in the narrative that other experiences are coming through.”

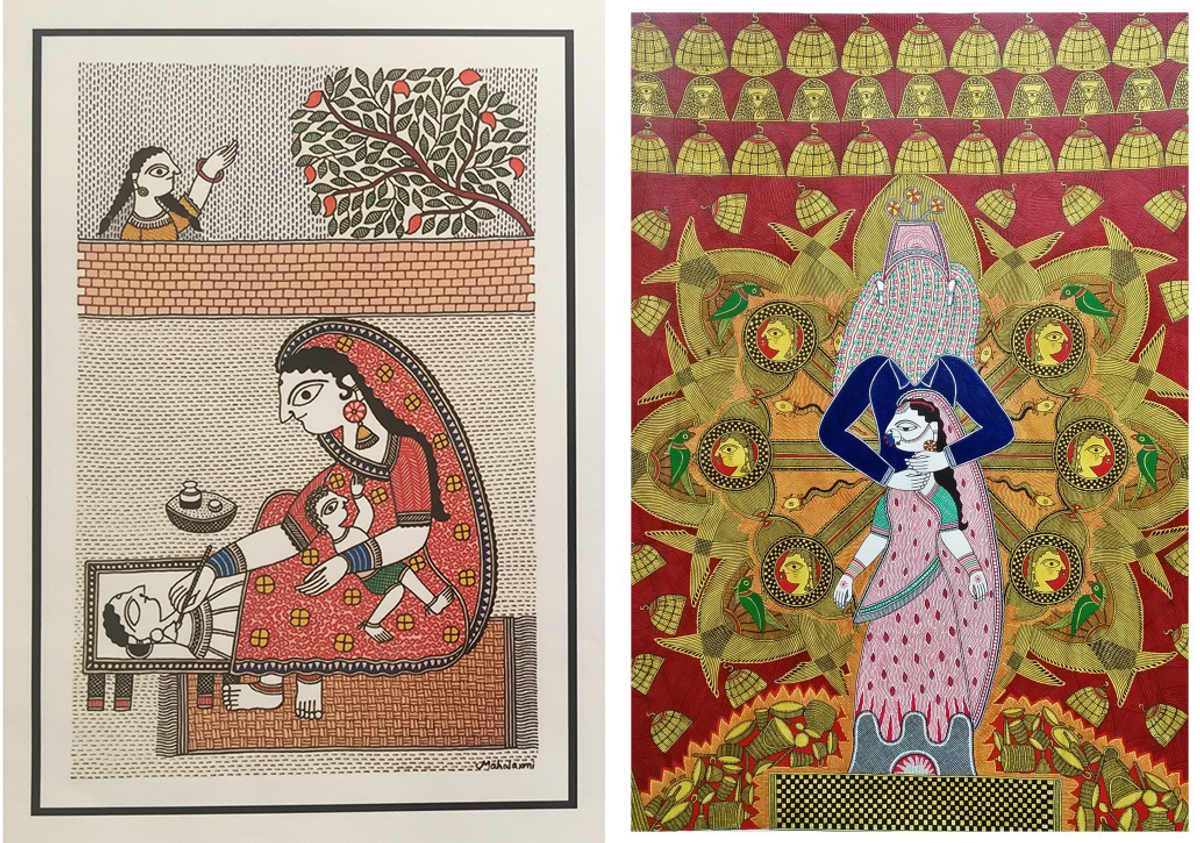

About 30 miles across the border, in Bihar, India, the mononymous artist Mahalaxmi unfurls a canvas on the floor of her home, flattening it to fill the space between a bed and a table cluttered with scrolls. The painting shows her recurring dreams, many of them images she associates with being a woman who deviates from gender norms here. A departing train symbolizes her need to travel, for instance; a bride riding a motorbike represents freedom.

Mahalaxmi lives with her husband and collaborator, Shantanu Das, part time in Ranti, a village in Bihar—the same place where they grew up, learned art, and encountered ridicule when they started dating before they were married. The village is located outside Madhubani, a small town on the edge of Nepal, known as the heart of Mithila art in India.

Standing over the canvas, Das says there are too many dreams to include them all. “She was always telling me, ‘In my dreams there’s a temple I’m not allowed to enter. I’m impure because I love someone.’”

“Now some of these dreams have stopped coming,” Mahalaxmi says. “Because we’re married.”

Each day in Madhubani, trains screech into a station where every inch of wall is painted in Mithila images: a smiling sun with a handlebar mustache, women collecting mangoes in a grove, buffalo plodding through a forest.

It’s part of recent efforts in India to preserve and promote Mithila art. As in Nepal, it’s been an important source of income for women in northern Bihar. The area—pockets of which are deeply impoverished—endures frequent and severe monsoon flooding each year. To support their families, many men and some women have left, migrating abroad or to other areas of India for work.

The collage that Mahalaxmi and Das unfurled was unfinished, one of several feminist pieces they’ve collaborated on—an arrangement considered unusual among Mithila painters. The pair have been working together since 2012.

The first step in their artistic process is to envision a concept and color palette together. Once they’ve done that, Das renders a loose composition of what images will be included in the painting, which Mahalaxmi—who is trained in line art—polishes and completes by drawing and painting.

Mahalaxmi and Das’s work spans a breadth of themes, from ritual depictions to a playful series on mermaids. Their feminist pieces have drawn acclaim in India and abroad; some have been exhibited in the United States. Their ongoing series, “Household Diaries,” depicts local women in what Mahalaxmi calls their “various incarnations”— wives, mothers, workers, painters. In one painting, a child hovers above his working mother like an apparition.

Other Mithila artists who have painted contemporary feminist themes include Amrita Jha, Shalinee Kumari, and Sangita Kumari. Each of these artists has touched on subjects such as women’s independence, dowries, domestic violence, son preference, inter-caste marriages, and other fraught societal issues.

One of the most celebrated Mithila artists who’s focused on gender issues is Rani Jha, a former social worker based in Madhubani whose work has dealt with purdah, female feticide, and male migration. Her favorite painting is called “Changing Women.” It shows four images of a woman evolving over generations. In the final frame, she wears a sleeveless blouse while her daughter lingers nearby.

“You can see her thinking, ‘Am I right or am I wrong?’” says Jha. “After some time, it becomes more clear. But even in the last scene, she’s still in confusion.”

Back at the studio in Nepal, Thakur mentions something that upset her that morning. On her way to retrieve Paswan and the other women, she passed a group of teenage girls hanging out in their village. Feeling discouraged after failing their exams, several said they had recently dropped out of school.

As Thakur explains that these girls belong to a so-called lower caste, her expression darkens, her tone sharpens. She says that Mithila trainings are expensive—people from “lower” castes can’t always afford them—and that she wishes the government would get involved and help make them more affordable.

She decides that she’ll return to their village to persuade the girls to finish school. If that seems unlikely, she’ll ask them if they’re interested in art.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook