An Elegy for India’s Single-Screen Cinema Palaces

Meet the photographer who has scoured the country to document these vanishing communal sites.

It was an unplanned detour that started the whole thing. On a lazy winter afternoon in January 2019, photographer Hemant Chaturvedi walked over to Allahabad University, an architectural landmark from the 1800s in the northern Indian city, to take a few images. En route, he remembered that there was an old, single-screen movie theater in the area. That’s how he ended up at Lakshmi Talkies, an Art Deco–styled cinema from the 1930s. Dilapidated after closing in 1999, the forlorn building was strewn with garbage and set to be demolished to make way for a new mall. “I have watched the thoughtless destruction of Allahabad’s, and the country’s, physical visual history, and I had the sudden urge to photo-document this space, before another niras [soulless] building replaced it,” Chaturvedi says. He found several surprises within. There was a dusty statue of the goddess Lakshmi in the foyer, her quartet of hands reduced to a trio. The auditorium walls had hand-painted murals of scenes from the Hindu epic, The Ramayana. A pile of old lobby cards, valuable collector’s items, spilled out of a cupboard. He went on to photograph a few more old theaters in Allahabad, and had conversations with their owners. It became clear that these single-screen cinemas—once social hubs nationwide—were fast disappearing because of financial constraints, apathy, and the arrival of modern multiplexes. This sparked Chaturvedi’s journey to conserve, visually, this cinematic heritage. Since then, the accomplished photographer and cinematographer has driven almost 20,000 miles, visited more than 500 towns in 11 states, documenting a total of 645 cinemas.

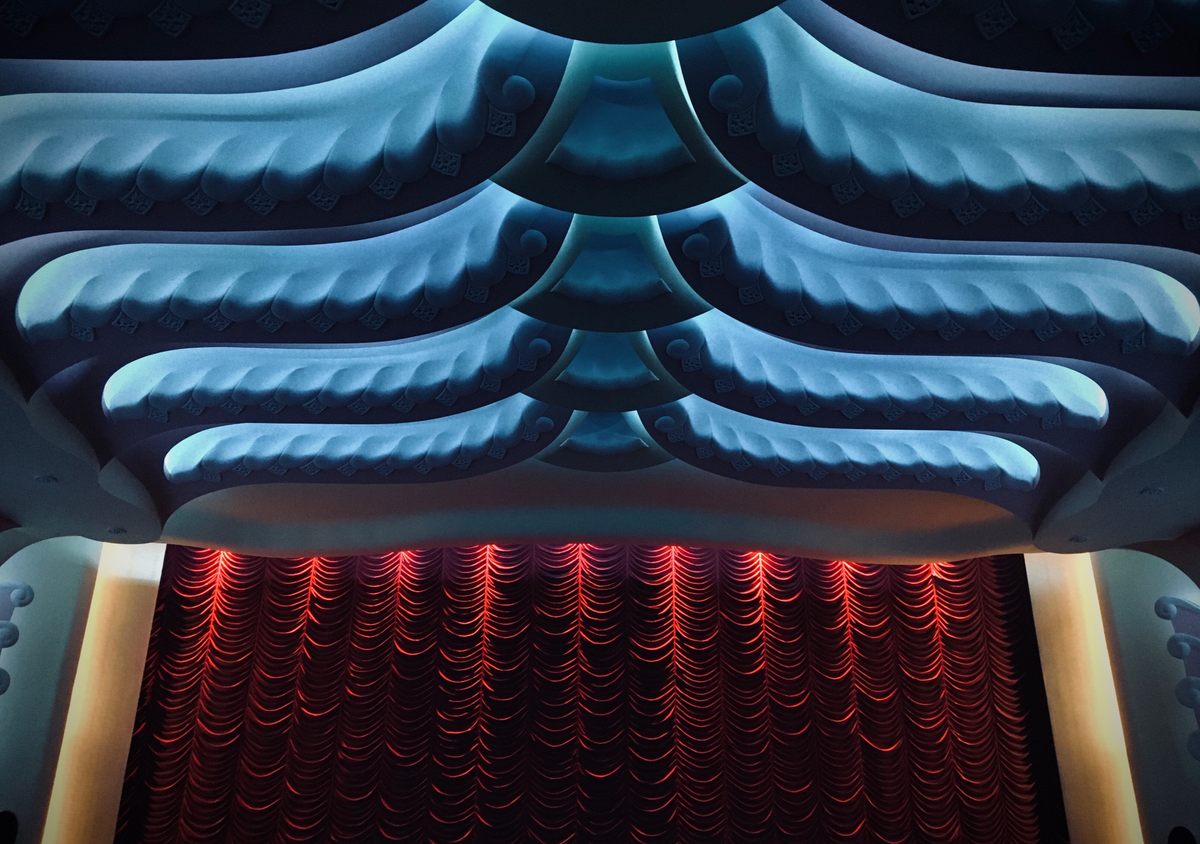

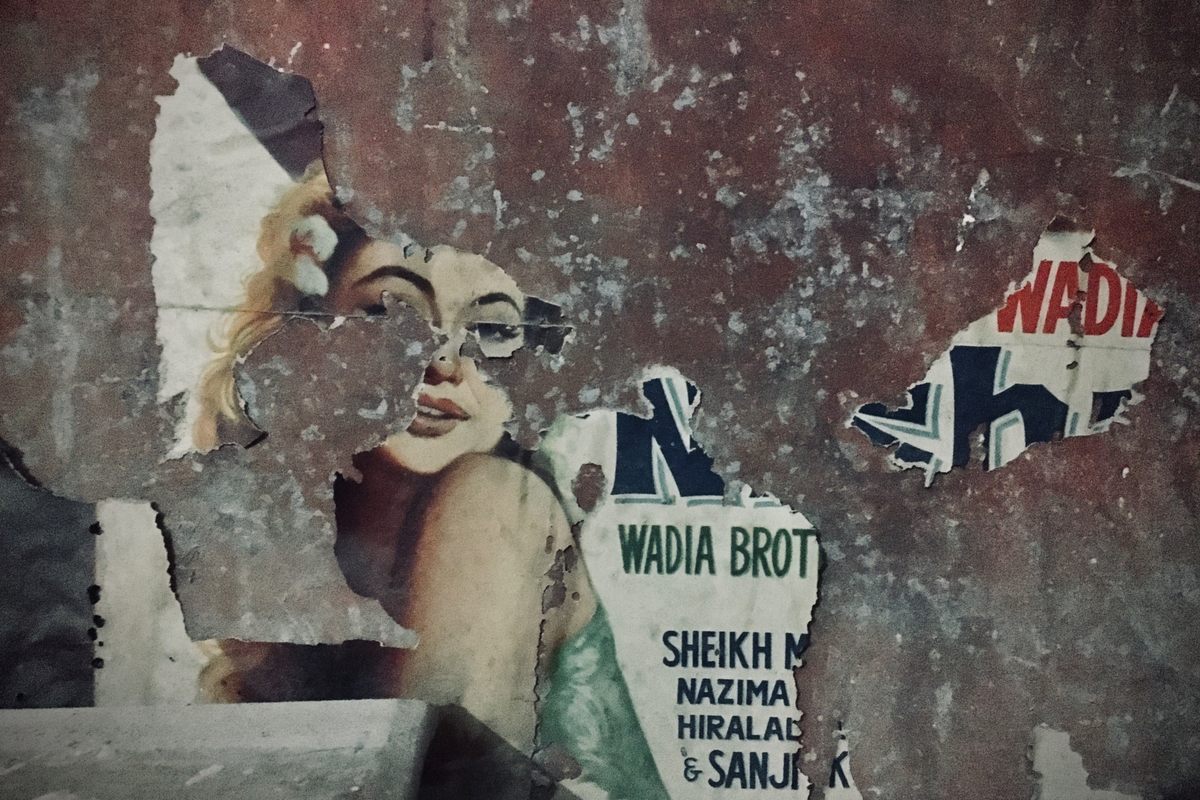

Chaturvedi’s photographs capture an astonishing amount of detail. There are wooden benches in the lower seating areas, dusty coils of film on the floor, magnificent Art Deco ceilings, stained spittoons, fragmented posters, and hand-stitched screens. The photographs showcase the distinctiveness of each cinema, and recall the frenzy and collective experience that has long marked filmgoing in the land of Bollywood: anticipation and excitement, snaking ticket lines, the thrill of black-market tickets for the “first-day-first-show,” coins flung at the screen by emotional viewers, the dark hall spilling over capacity, the hum of the projector.

India today is the largest producer of films globally, with around 2,000 a year, selling (under normal circumstances) two billion tickets annually. In 1896, the French Lumière brothers, pioneers of early motion pictures, came to India to show their films at Watson’s Hotel in Bombay, selling tickets for Rs. 1 (about a penny). The first purpose-built cinema hall was Kolkata’s Elphinstone Picture Palace, built in 1907 to show films from overseas studios. But film exhibition existed even earlier, in spaces such as ”bungalow cinemas,” where the wealthy converted space in their sprawling homes for screenings, and “tent cinemas” that traveled from town to town. In 1913, Dadasaheb Phalke, considered the pioneer of Indian filmmaking, produced the first full-length Indian motion picture, Raja Harishchandra, a silent Marathi film.

“Theater already existed, catering more to the wealthy. Cinema was created for the masses,” says Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, Indian filmmaker, archivist, and founder of the Film Heritage Foundation. “The significance of single-screen cinemas was the shared experience. Filmmakers and viewers wanted to create and watch movies on the big screen. That immersive experience of watching a film together with 500 to 1,000 people cannot be replicated.” Smaller towns usually screened films months or even years after a movie’s release, once the print became affordable. Chaturvedi was told the story of a town in Gujarat in the 1950s, where a designated person was sponsored by the townspeople to visit the large city of Ahmedabad to watch a newly released movie. On his return, he would narrate the story to a gathered crowd, often embellishing details (as they would all discover when they finally watched the film).

Autorickshaw drivers help Chaturvedi scout an area’s old cinemas, while caretakers, canteen owners, projectionists, and neighboring juice or tea stall operators—their livelihoods also affected by the decline of these spaces—provide more information and stories. At Malwa Talkies in Patiala, he met Gurbaksh Singh, the resident projectionist since 1974. “His driving license from 1976 had a photo of him in a Sikh turban with a beard,” says Chaturvedi, who asked Singh why he was clean-shaven and turban-less. “The long working hours and heat generated in the projection room made him choose between his visible faith and the faith of his convictions. He chose to discard the turban since he had less time to wash his hair and maintain his visible Sikh identity.”

The decline of single-screen cinemas began in the 1980s and 1990s, with the widespread availability of television and the arrival of multiplexes. In 2009, there were 9,710 single-screen cinemas, down to 6,300 by 2019. High taxes and distributor rates, the shift from celluloid to digital, weaker content, competition from multiplexes, and the decline of black marketeering of tickets all contributed to their disappearance. They appear to be taking Indian cinema’s inclusive spirit with them. “Regardless of religion, community, or social strata you were entertained in the same space, the only difference was the seats you could afford,” says Chaturvedi. “I found lower-stall wooden benches with no partitions, where a family of four could buy two tickets and squeeze themselves in to watch a movie.” Several standalone theaters now show B- and C-grade movies—usually action, erotica, or horror—as a cheaper option for those who cannot afford the international multiplex experience.

With the pandemic hastening the decline of the surviving single-screen cinemas, Chaturvedi feels an urgency to capture this vanishing culture, as few are invested in its preservation. “The industry is not interested in preserving their own films, the battle for declining cinema halls is even less of a priority,” says Dungarpur, who nevertheless remains optimistic. “Cinema will recover even if the pandemic slows it down. Many single-screen cinemas will close, but several will survive to cater to the masses.” Chaturvedi intends to draw his documentation to a close this year. Plans for a series of books and exhibitions are underway to celebrate these unique spaces in cinematic history, where at one time anyone could immerse themselves in a larger-than-life experience.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook