See America’s National Parks—Before They Were National Parks

Landscape photography like this helped create the National Park system.

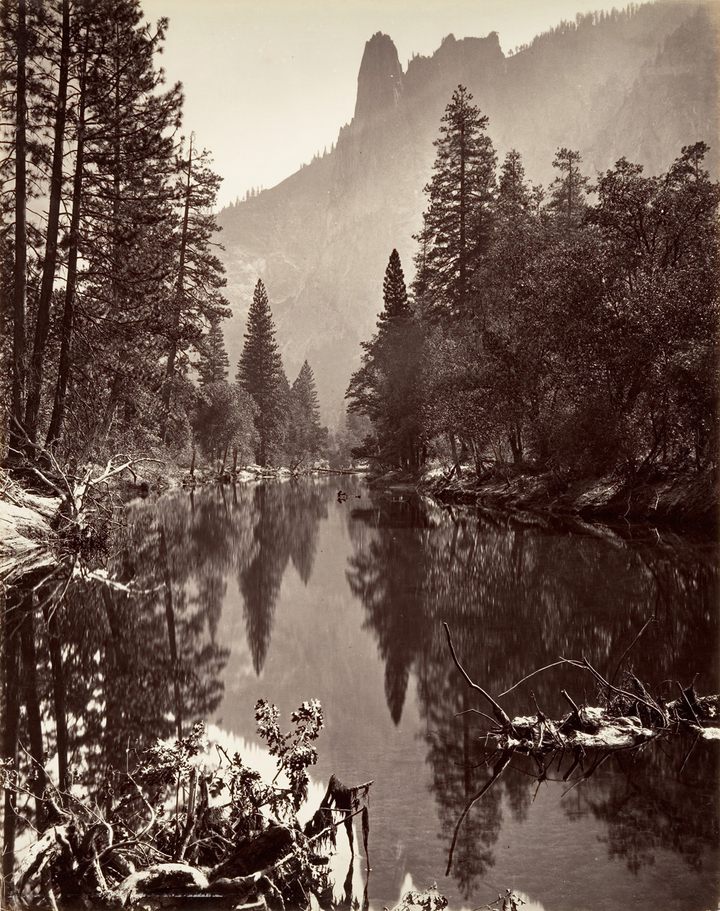

In 1861, photographer Carleton E. Watkins lugged his custom-made oversized camera, designed to shoot on unusually large glass plate negatives, measuring 18 by 22 inches, to Yosemite in California. It was roughly 2,000 pounds of photography equipment that went with him, on the backs of mules, through the challenging terrain. His “mammoth” photos, using a difficult wet-collodion process, of such wonders as El Capitan, Mariposa Grove, and Cathedral Rocks, revealed an exquisite bit of Eden to viewers, especially those on the East Coast. “These earliest photographs of Yosemite resulted in a body of work that was to shape one of the early acts of environmentalism in U.S. policy,” writes Bob Ahern, Getty Images’ Director of Archive Photography, in an email. It was believed that the images of Yosemite influenced President Lincoln to sign the Yosemite Valley Grant Act in 1864, which protected the land to “be held for public use, resort, and recreation,” and would lay the foundation of the country’s National Park System.

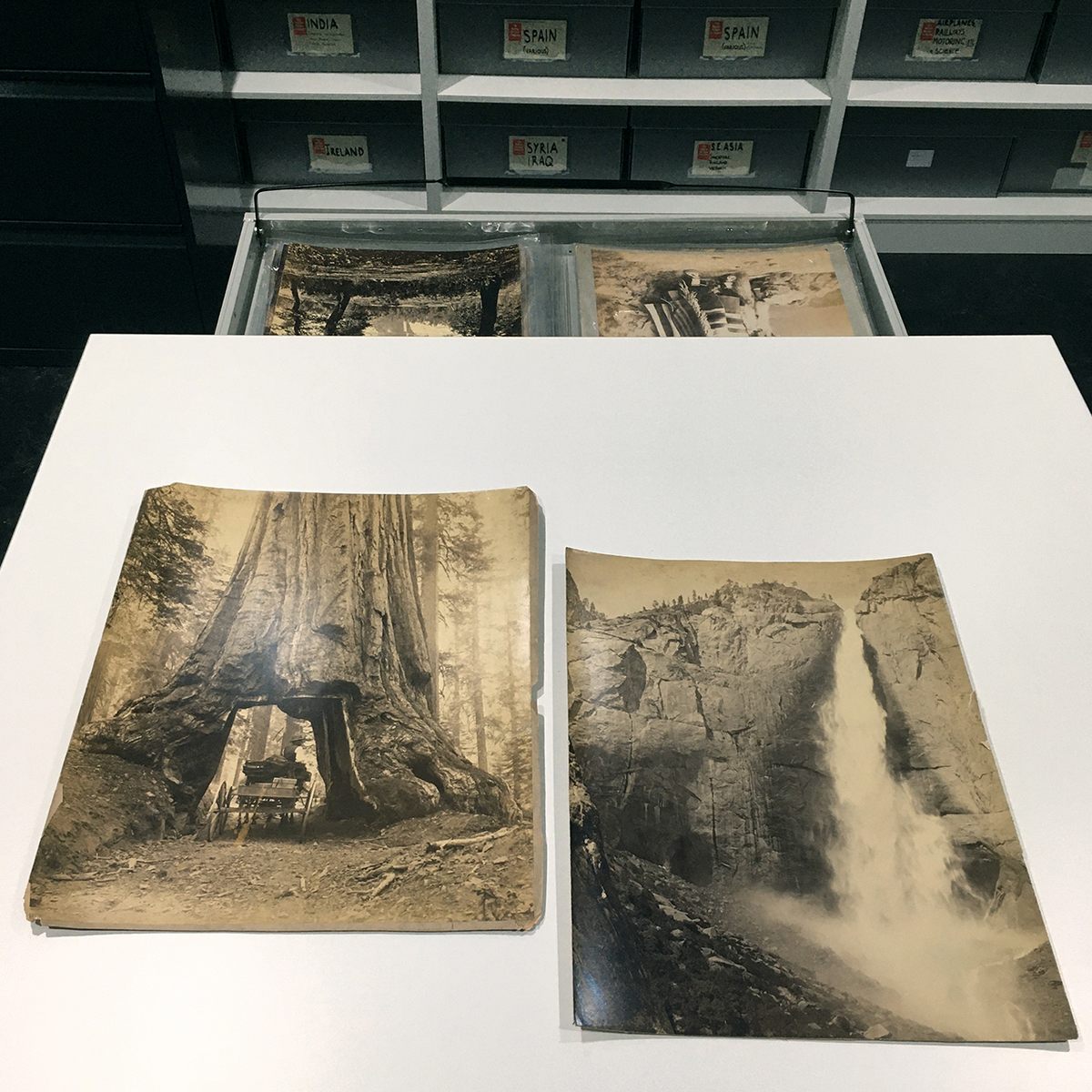

Over the years, Watkins returned to Yosemite seven times to photograph its grandeur, and his distinctive images won him international acclaim and awards. A fire at his studio during the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, however, destroyed most of his work. But a part of Watkins’s legacy lies in a drawer of the Getty Images Archive. “With enlargers not being developed until much later, the set of [Watkins’s] photographs now preserved at our Archive are original contact prints—prints produced in direct contact with the [glass] negative,” says Ahern. “And through this process Watkins has skillfully and artfully distilled the sublime beauty of Yosemite into just 18 by 22 inches of gold-toned albumen print.”

Yosemite National Park celebrates its 130th anniversary in 2020. As Watkins’s photos influenced the future of Yosemite, Ahern believes landscape photography can have a real world impact—one that is even more important today. “Photography has the power to inspire change in terms of how we treat our environment and for this reason, has never been more critical,” he says. “As the world faces unprecedented challenges around climate change, I cannot think of a more pressing time to photograph our impact on the natural environment.”

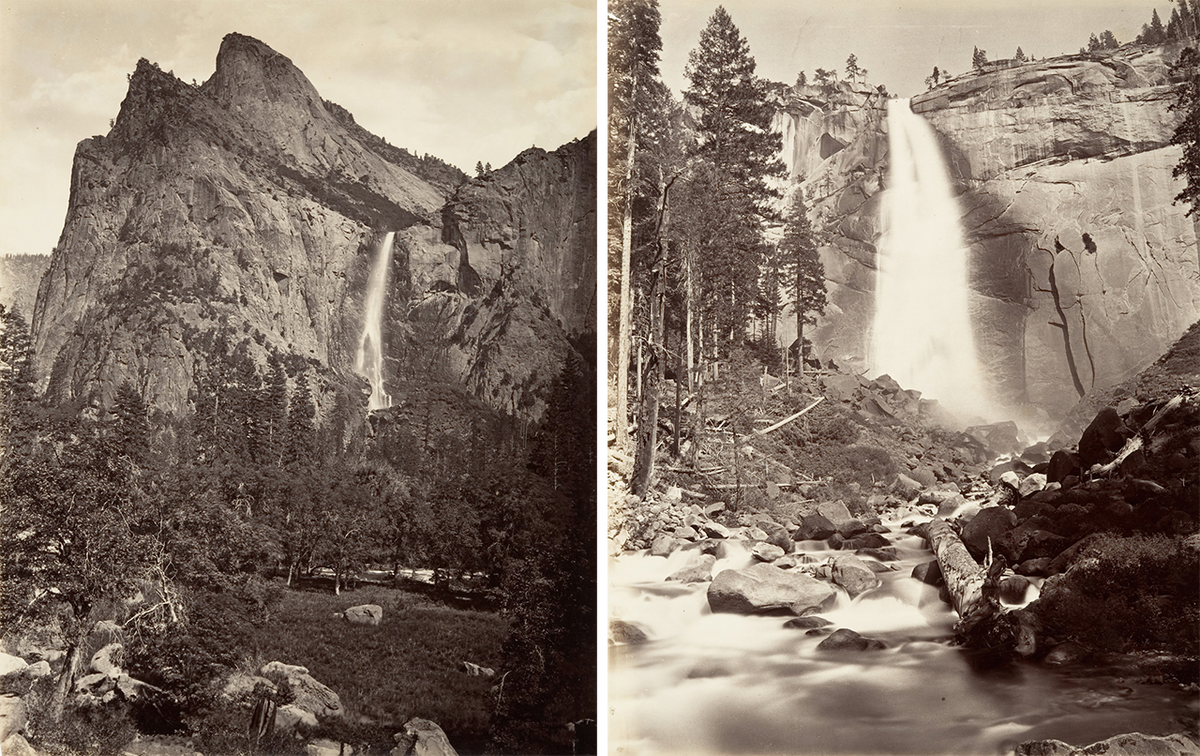

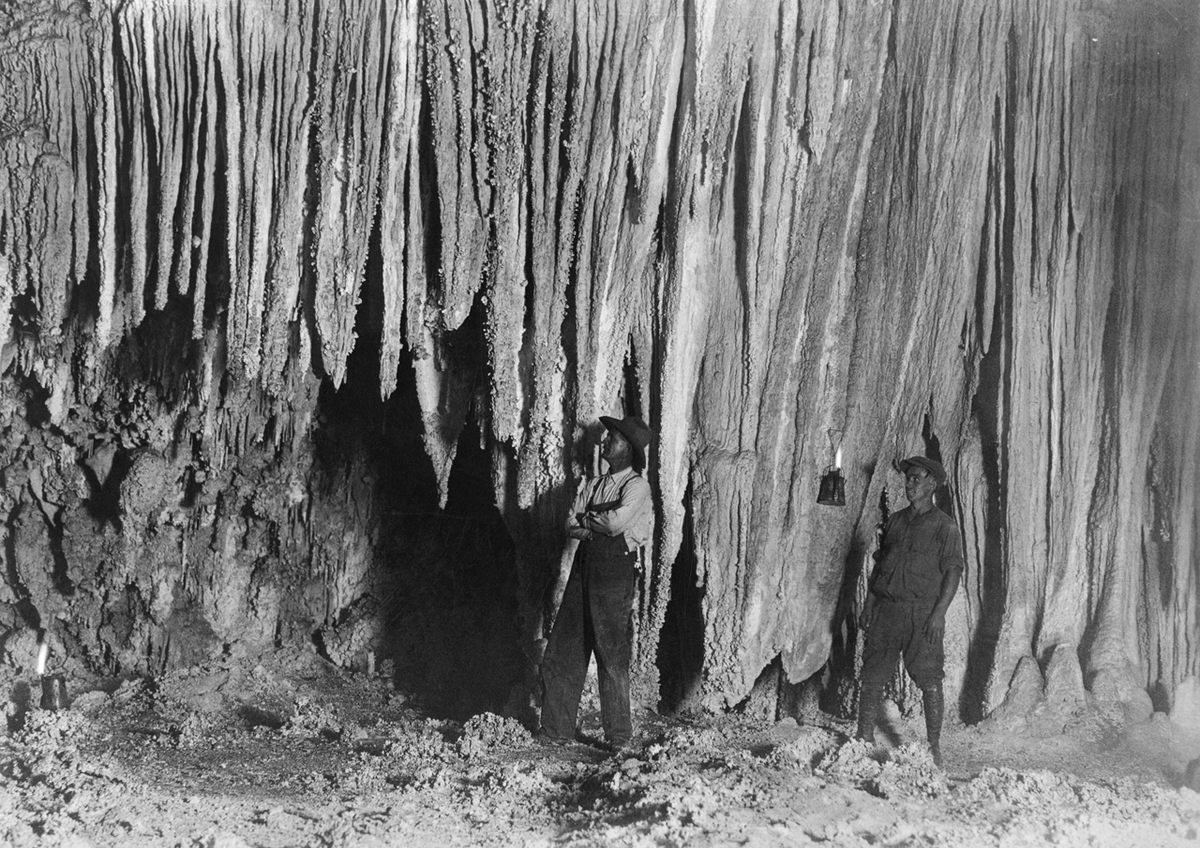

Here are other alluring views—by a number of other photographers—of natural wonders that would eventually become part of the U.S. National Park system.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook