The Israeli Hotel Where COVID-19 Recovery Meets Standup Comedy

When every guest is a coronavirus patient, you’re allowed to hug, hang out in the lobby, and gather for meals.

Noam Shuster-Eliassi was supposed to debut her one-woman standup comedy show, “Coexistence My Ass,” in the U.S. this year. Instead, in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak, she tried out the routine in Israel, performing in front of strangers who crowded into a noisy lobby. Later, she joined them for Passover at tables laden with watermelon and wine. The atrium echoed with the sound of laughter, singing, coughing, and conversations in Hebrew and Arabic. Almost no one wore a mask.

This was the scene inside the Dan Jerusalem Hotel, where people of all political and religious stripes stay as they recuperate from COVID-19. They have already been sick and are thought to have gained immunity to the coronavirus—making this one of the few places where the rules of social distancing don’t apply.

Before her sojourn at the hotel, Shuster-Eliassi had been at Harvard Divinity School on a fellowship to develop her standup act, which she performs in Hebrew, Arabic, and English, and was performing with the Iranian-American comedian Maz Jobrani. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Harvard shut down, so Noam decided to take a chance and fly home to Israel. She had a layover in New York City.

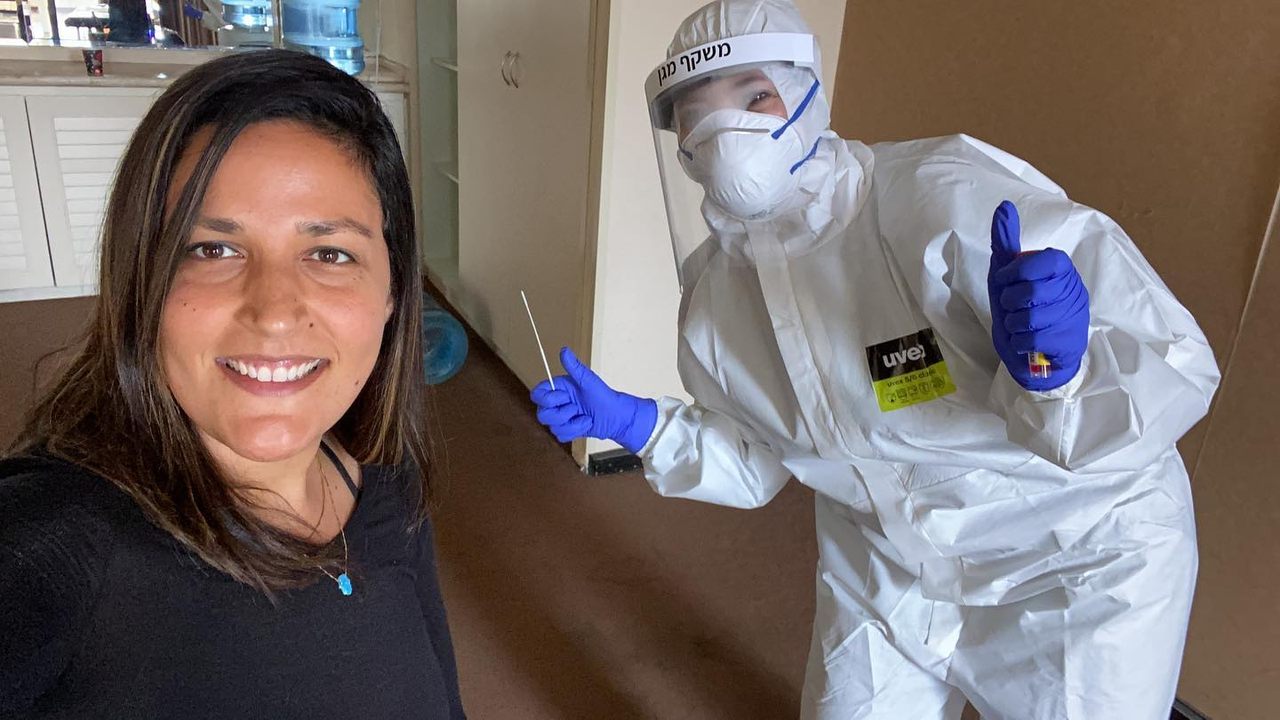

Within days of her flight, Shuster-Eliassi had developed COVID-19 symptoms and had to go to the hospital for supplemental oxygen. And there, her unfortunate situation led to a unique opportunity. “I did stand-up shows here in the lobby,” says Noam. “The fact that I got sick let me do what no other comedian is doing today: a show with a real audience, not on Zoom.”

The quarantine efforts at the Dan Jerusalem Hotel are coordinated by the Israeli military, part of a country-wide effort to control the spread of COVID-19. As of May 12, there have been more than 16,000 confirmed coronavirus cases in Israel and 258 deaths; all residents returning from another country are required to undergo a 14-day quarantine. Palestinian hospitals in the West Bank have faced shortages of medical equipment, and the Gaza Strip had only 90 ventilators for a dense population of two million; the threat of land annexation by Israel lingers, with reports of increased violence from Israeli settlers against Palestinians.

Hotels throughout Israel have been appropriated so that COVID-19 patients can quarantine and convalesce. “We have a special case here in the Jerusalem hotel, because the young people are taking care of the old people, there are Mizrahi, Ashkenazi, secular, religious, Palestinian, Jewish,” says Shuster-Eliassi, laughing. “I don’t know what this is, but we’re all getting along and I’m having the biggest identity crisis of my life.”

That sense of intense community at the hotel has been a balm for people who were very sick and isolated before they arrived. “One of the women that I really connected with is a Palestinian from Jerusalem, her name is Rafa,” says Shuster-Eliassi. “She’s a midwife who works in a hospital, and she lost her husband a month ago to cancer … She caught the virus and she left five kids at home.”

Shuster-Eliassi was moved by their friendship. “We made each other happy,” she says. Because they were around others who had tested positive for COVID-19, they were able to give and receive hugs. “Imagine, she has to get sick and come to this hotel to get hugs,” Shuster-Eliassi says.

Sima Segal, another hotel resident, had health problems for a decade before the pandemic. She had a constant cough and frequent fevers starting in 2010, and a parade of doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong. This February, she went to see a specialized doctor who ordered a CT scan; as a high-risk individual, she also got tested for the coronavirus. When the tests showed she had both a lung infection and COVID-19, she almost fainted from fear and anxiety.

When Segal moved into the Dan Hotel, she spent a few days crying in her room. Then she ventured out into the riotous lobby, where she found her spirits buoyed. “At the age of 70, it’s an amazing experience to meet young people,” Segal says. “To be welcomed and hugged by young people who are having so much fun with me.”

Though the hotel provides food for the recovering patients, the residents are mostly left their own devices. One resident offered sunset yoga classes on the roof, while others played music on the hotel piano. Eden Dori, an asymptomatic 21-year-old, started a nightly Zumba class in the lobby. Every night at 6 p.m., she bounced and wiggled in front of participants in leggings, who filled the floor and shook their hips to the music. “Sometimes people don’t do Zumba with me, but they just watch us,” said Dori.

Shuster-Eliassi grew up in Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam, a village jointly founded by Israeli Jews and Arabs to promote peaceful coexistence, and she is fluent in Hebrew and Arabic. In the hotel, she says, prejudices and societal divisions seemed to fall away. “I met an ultra-Orthodox man that was just constantly interested in why I’m speaking Arabic, and why I’m hanging out with the Palestinians, but from a very very good place,” she says. He was genuinely curious about her upbringing in the village, and the interaction was one of many reactions that surprised her. Remembering all this, she laughs. “We’re all getting along—like, what the hell is going on?”

Shuster-Eliassi left the hotel on April 19, after finally receiving the required two negative tests for the coronavirus. Leaving was an emotional experience. “There was a sense of leaving a family,” she says.

Now separated from the community at the Dan Hotel, she is trying to process what she experienced there. She is careful to point out that the hotel felt like a home because it was so separate from the asymmetrical power dynamic of the real world. “In the hotel, Israelis and Palestinians got the same. We got the same meals, the same treatment, because it’s a national effort that we all don’t get each other sick,” she says.

In her comedy routines, Shuster-Eliassi is often cynical about the possibility of coexistence in such a fraught political environment. But this experience has restored a little bit of her hope. “Israelis will never be okay if Palestinians are not okay,” she says. “We live in the same land. And we didn’t need this virus to teach us that. But this is what I saw in the hotel.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook