Found: A Medical Manual Linking Medieval Ireland to the Islamic World

Knowledge transcends borders.

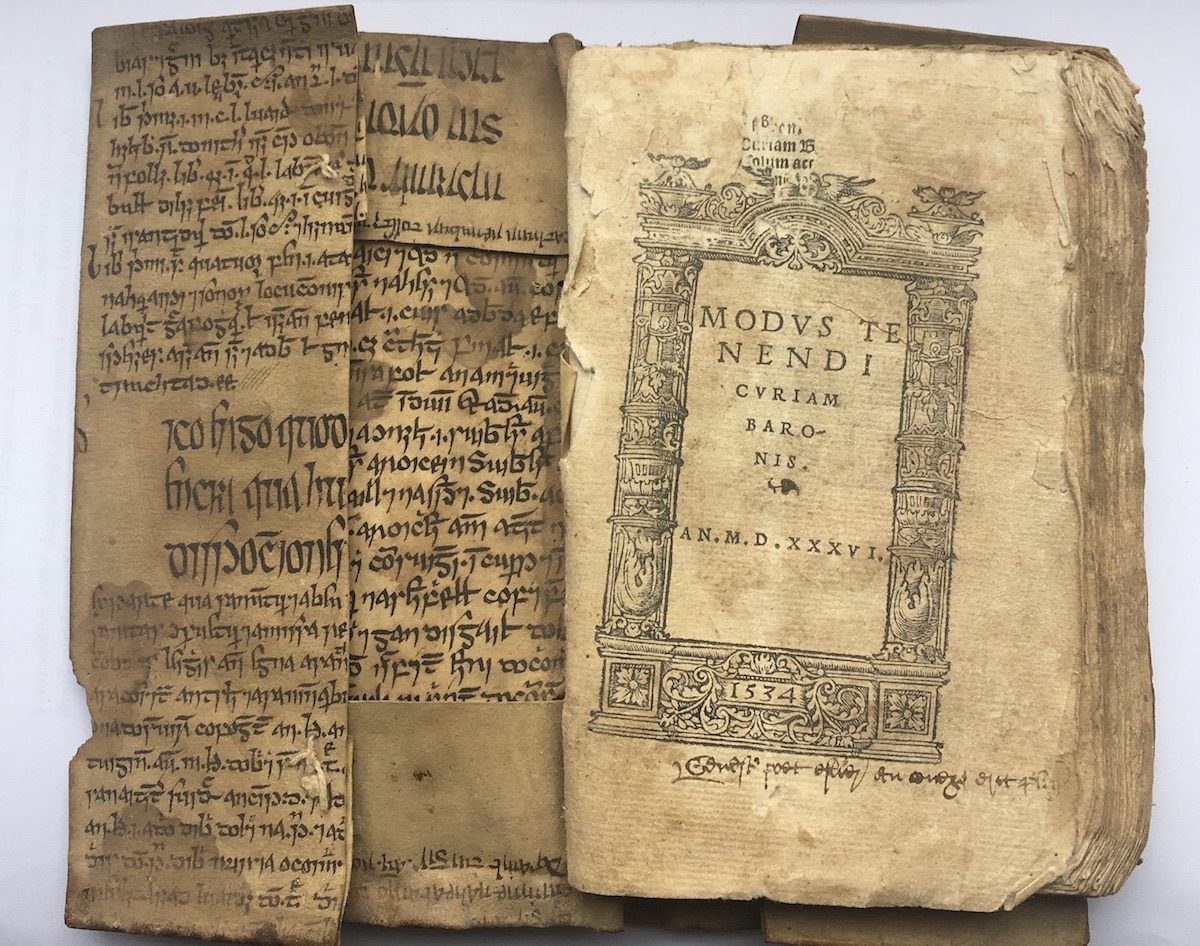

An exciting link between medieval Ireland and the Islamic world has been discovered on two sheets of calfskin vellum lodged into the binding of a book from the 1500s. The sheets hold a rare 15th-century Irish translation of an 11th-century Persian medical encyclopedia. For 500 years, they sat in a family home in Cornwall with no one the wiser to their origins.

“I suppose [the owners] just took a notion to photograph it with their phone and they sent the photograph to one of the universities in England, who sent it to another university, and eventually it got to me,” says Pádraig Ó Macháin, who has spent his life with medieval Gaelic manuscripts and leads the modern Irish department at University College Cork. For him, identifying it as a medieval Irish medical text was a cinch, but he needed a little help to determine its source.

Ó Macháin, founder of Irish Script on Screen, Ireland’s first deep digitization project, where the manuscript and many more old Irish texts can be seen, shared the fragment with Aoibheann Nic Dhonnchadha, a specialist in Irish medical texts at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. She identified it as a passage from the first book of the seminal five-volume The Canon of Medicine. Written by 11th-century Persian physician and polymath Ibn Sina, also known as Avicenna, the work is considered the foundational textbook of early modern medicine. While many references to Ibn Sina and his work pop up in old Irish medical texts, this is the only known evidence of a full translation of his encyclopedia. He originally wrote in Arabic, and the Irish rendition is likely translated from a 13th-century Latin version by the prolific Gerard of Cremona. “This is one of the most influential medical books ever written,” says Nic Dhonnchadha. “So the fact that it was being studied in Ireland in the 15th century was certainly a link to the Islamic world.”

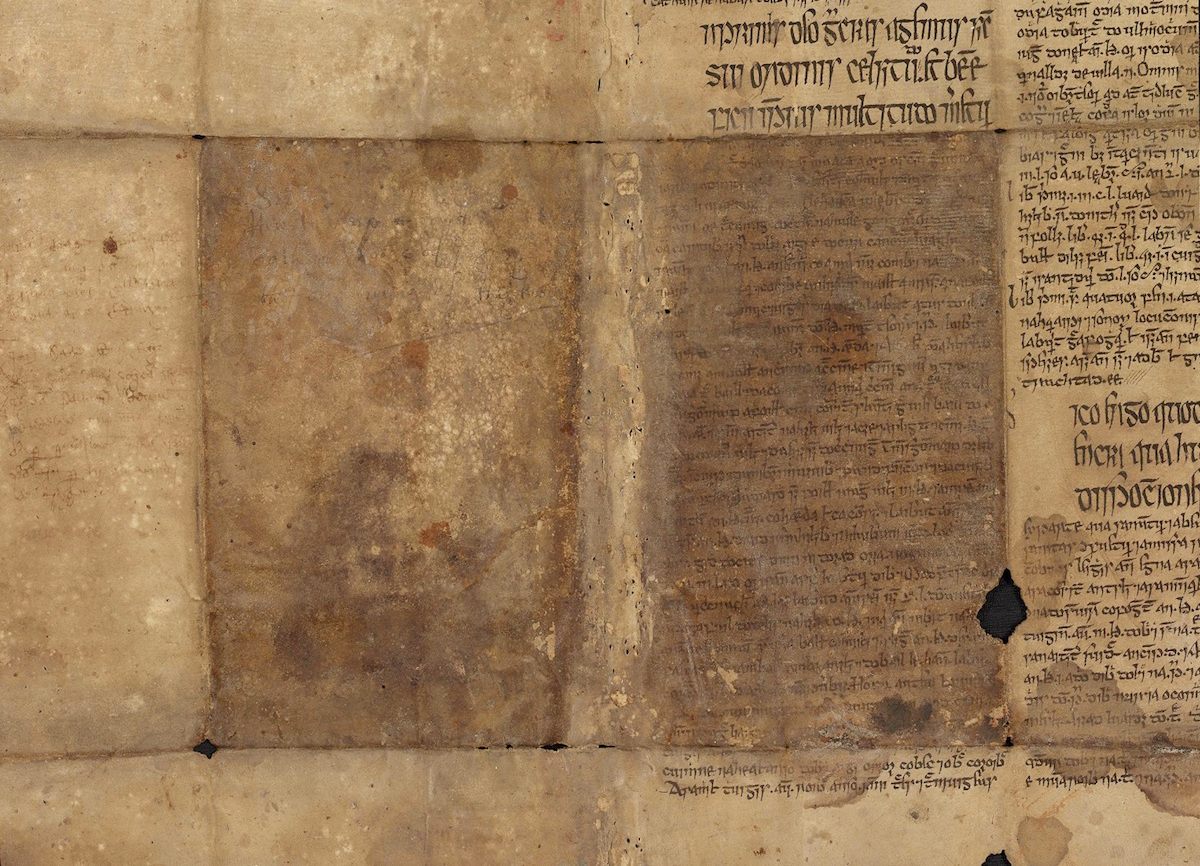

The heading at the top right of the page is Ibn Sina’s preface to his Canon, in Latin. It gives thanks to god and explains that one of his friends asked him to write a book about medicine (quite the favor!). The rest of the text is in Irish, peppered with transliterated Latin terminology. One sheet runs through the encyclopedia’s contents, while the other details the anatomy of the jaw, teeth, nose, and throat.

Using scraps of old manuscripts to bind newer books was a common practice as the world transitioned from handwritten to printed words, but it would have been unusual for such a precious text to have been taken apart on purpose. “These kinds of manuscripts would have been very valuable to the people who owned them,” says Nic Dhonnchadha. “Anyone who owned it would have been unlikely to part with it.” Many manuscripts were destroyed during England’s encroachment upon Ireland, and the scholars believe that the Canon manuscript suffered such a fate. It’s just a stroke of luck that this fragment was salvaged and used to bind a much-less-interesting administrative text.

Ó Macháin hopes the find can help overturn some misconceptions about Ireland at that time in history. “Ireland was very much pre-urban, and we remained pre-urban until the 17th century,” he says, “but what people don’t understand is that there were great schools of learning here, including medical schools.” In these Irish medical schools, unlike those in England or continental Europe, students studied in Irish rather than Latin, creating a unique repository of medical knowledge in a vernacular language. Nic Dhonnchadha’s upcoming full translation of the manuscript will reveal some key differences between the Latin version and its Irish counterpart.

“This is an example of learning in its purest form, it transcends all boundaries, it transcends cultures and religions, it unites us all in a way that other things divide us,” Ó Macháin says. “That’s very personally important to me because I think learning is without borders and that this is maybe an opportunity to express that and make people understand it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook