How an Italian Writer’s Imaginary Garden Became a Place of Literary Pilgrimage

Soon, the Garden of the Finzi-Continis may no longer be a fiction.

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis is not a real place. We should say that first. You’d be forgiven for thinking that it is, and you wouldn’t be alone. It was invented in Giorgio Bassani’s 1962 historical novel of the same name, and in the 1970 Oscar-winning movie adaptation. It is a place of young love, refuge, and tennis, a place so carefully and lovingly described in the book that many devoted readers are certain it must be there, somewhere in the city of Ferrara, in Italy’s northeastern province of Emilia Romagna. And so thanks to literary imagination, countless travelers and tourists have made a secular pilgrimage to Ferrara’s wide avenues.

“There are hundreds of people every week. Some people came from the Mississippi Valley three days ago, from St. Louis, Missouri. ‘But where’s the garden? We want to see the garden,’” says Portia Prebys, Bassani’s longtime companion, from the city’s Center for Bassani Studies. “People come all the time and they’ll ask in the hotels, ‘But where is the garden?’ They think it really exists, you see.”

In the story the garden is the patrician home of the Finzi-Continis, an aloof Jewish family whose estate is off-limits to outsiders—until the shadow of anti-Semitism looms over the city. It’s 1938 when the heart of the story begins, and a group of Ferrara’s bright Jewish youths go to the garden as a haven from the new fascist Racial Laws. Its allure, as a place of both mystery and safety, has weathered decades, even though no guidebook or mapping service can offer its location. Bassani’s novel does actually offer directions, with real landmarks along the way, which has convinced studious tourists that it will be there. But, to a person, they are disappointed. However, in a strange twist, the constant search for the garden may lead to its creation.

“Ferrara is perfectly described [by Bassani], so many tourists come after reading the book and are surprised when I explain the garden isn’t really there,” says Emanuela Mari, a city guide who has been leading people to the sites of Bassani’s fictions since 1995. “Generally I make clear before their arrival that the garden doesn’t really exist.”

This absence, Mari contends, does not preclude the search, or its possible rewards. “When you walk through the main street, Corso Ercole I d’Este, you go to ‘the infinite,’ Bassani tell us that,” she says. “The garden is at the end of it.” Wandering the Renaissance infinite does sound like a rewarding, if fruitless, way to spend a morning.

The Corso traverses Ferrara northward from its center, like a timeline that traces the peak and decline of the dynasty that oversaw the city’s golden age. Its mossy cobblestones date back to the 15th century, when Ercole I, of the Dukes of Este, commissioned architect Biaggio Rosseti to create a feat of urban planning. Known as the Herculean Addition, the project doubled Ferrara’s size and molded it into an “ideal city” of the Renaissance. The medieval constriction of the town’s oldest districts gave way to the harmony and decorum of straight, wide streets, rational lines, and “infinite” perspectives lined by palaces and brick walls. The Corso runs from the Estes’ castle to the Gate of Angels, through the city walls. It is said that heirless Cesare d’Este, the last duke, departed the city for the final time through this gate in 1598, when his lands were taken by rival Papal states.

There is, just down the Corso from the Diamanti Palace—sheathed in diamond-shaped marble and now home to city’s the National Painting Gallery—a fence in front of an trimmed, empty green space. On the fence, at 25 Corso Ercole I d’Este, hangs a weatherbeaten sign that reads (in Italian): “The garden that isn’t there.” The site was long abandoned and overgrown. The sign and others like it around the city are the work of a local cultural organization and are related to a proposed art installation with the same name—an indication of just how important the garden has become to the city’s identity and Europe’s 20th-century history.

“The Garden of the Finzi-Continis is a story that marked my city, it is a story in which the city is the protagonist,” mayor Tiziano Tagliani stated this June, when the novel was included in the city’s graduation exam that all students take to complete their secondary education. The choice was inspired partly by last year’s 80th anniversary of the adoption of the Italian Racial Laws—Mussolini’s 1938 answer to Hitler’s earlier anti-Semitic legislation—the shadow that looms over both Bassani’s life and his masterpiece.

The word “ghetto” is thought to have originated in Italy, in reference to the site where Venice forced its Jewish residents to live in 1516. Under the rule of the Estes, there had been no such place in Ferrara. They had maintained their city as a haven, which contributed to the city’s cultural bloom. But when their rule ended at the end of the 16th century, a triangle of blocks off the city’s main square became the Jewish ghetto, and its gates were locked at night. They seemed to swing open permanently in 1860, during Italian Unification, and Jews appeared to become full members of the nascent country.

By the 1920s, many Jewish residents of Ferrara had become members of the Partito Nazionale Fascista, the country’s fascist party. From 1926 to 1938, the city’s podestà, the local representative of the fascist regime, was Jewish politician Renzo Ravenna. Bassani’s father was a member as well. But the ideology soon curdled with anti-Semitism.

Bassani, then a bright student in his early 20s, was expelled from the local tennis club, and later he was only allowed to teach at the Jewish school in the former ghetto. There were no locked gates anymore, but the barriers set by law established a ghetto without boundaries. Bassani had rejected fascism even before this and in 1943 he spent three months in jail for his views. By the fall, Italian Jews were being transported to death camps. He had to leave the city he loved.

“He was forced to leave to save his neck, and he never returned to live in Ferrara,” Prebys explains. “He couldn’t go back, it could never be the same.” Bassani went into hiding in Florence then established himself in Rome until his death in 2000. Only then did he return—to the Jewish cemetery.

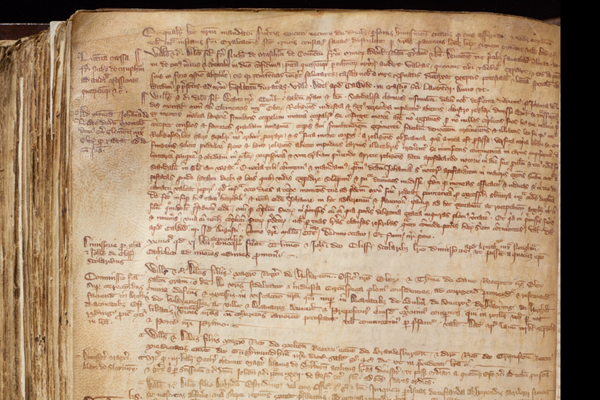

In 1956, Bassani had published Within the Walls, the first of six books collectively known as The Novel of Ferrara. The works, including the third volume, The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, established and then cemented Bassani as one of the greatest Italian writers of the century. In the books, he recreates the city and community he’d left behind, an act that some people did not appreciate. “It was the time of silence, of shame, of opportunism,” Silvana Onofri, director of Giorgio Bassani Foundation, explains. “The bourgeoisie, be it Jewish or Catholic, had not stirred the Shoah, it had only removed the fascist past.” In the process of defying the city’s collective amnesia, Bassani created a memorable garden.

Today, along the pathway on the old city walls, visitors can be seen peering down, in the hopes of seeing where the story begins. At the outset of the novel, somewhere below the ramparts, a girl named Micòl Finzi-Contini stands on a ladder propped against her garden wall, and invites a boy to climb in. Years pass before they finally meet inside, as young adults singled out by the Racial Laws. The garden is a great park around the aristocratic family’s home, and provides—temporarily, at least—a refuge from the darkness beginning to envelope the city. There, the main characters have a final season of love and dreams and tennis. It’s an idyll that begins and ends by climbing a ladder over the wall, like an inverted escape or illegal migration, not out of a ghetto but into a safe place. Cast away from Ferrara, Bassani invented his own Eden, there, in its heart.

“The garden is an ideal, it’s like getting back to paradise. What Giorgio is denied by the Racial Laws, he can have it back in this ideal place,” the guide Mari says.

“A place where he could withdraw to,” Prebys calls it. “It looks as if you could go there today, because he was so precise in his description.”

The safety was, of course, an illusion. Afterwards, Bassani writes, the Finzi-Continis were “deported in Germany in 1943, and no one knows if they have any grave at all.” The only memorial to this fictitious family is the fictitious garden he made for them—a memorial without a place. But that could soon change.

“In a few months, an Israeli sculptor named Karavan is going to do an installation,” Prebys says. “As soon as it goes up, people will believe that this is where the garden was. The search for the garden will stop.”

From his studio in Paris, Dani Karavan remembers the moment the idea came to him, in the 1970s. It was in the course of his studies in Italy, during a visit to Ferrara. “When the film came out I saw a Pullman bus with American tourists coming to Ferrara to see the Garden of Finzi-Continis. ‘But it doesn’t exist,’ I thought. ‘Only in the book.’ So I had the idea to do a project, The Garden That Doesn’t Exist.”

Nearly half a century later, now aged 88, Karavan has brought his idea back to the place that inspired it. His work was recently shown in Ferrara’s National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah—at the site of the prison where Bassani was once held. Among the pieces was Karavan’s model for the garden, planned over the last 15 years and closer than ever being built—if he can get the funding.

Of course, this memorial will not be the garden of so many people’s imaginations. Karavan describes a structure at the crossroads of sculpture and architecture: large walls of glass covered in passages from the book in multiple languages, with an opening in it like a garden gate. Railway tracks interrupt it, evoking the deportations to death camps. Around the wall will be green grass, and inside only sand. And against the wall will rest a ladder, like the one used by the novel’s characters.

It’s perhaps different enough that it will welcome both those who value the garden as a symbol of hope, and those who simply want a place to go to pay their respects to Bassani.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook