How a 14th-Century Nun Faked Her Own Death

Her escape was documented in the margins of a medieval manuscript.

In the 14th century, York was the most important city in England, next to London. This northern hotspot was a center for international trade, particularly in the wool industry. Around the city, it wasn’t hard to find clothing merchants, butchers, artisans, and tanners selling their goods. This period in the city’s history is often described as the “Golden Age of York.” Yes, York was indeed a bustling hub of medieval city life—a life perhaps too tempting for a young nun.

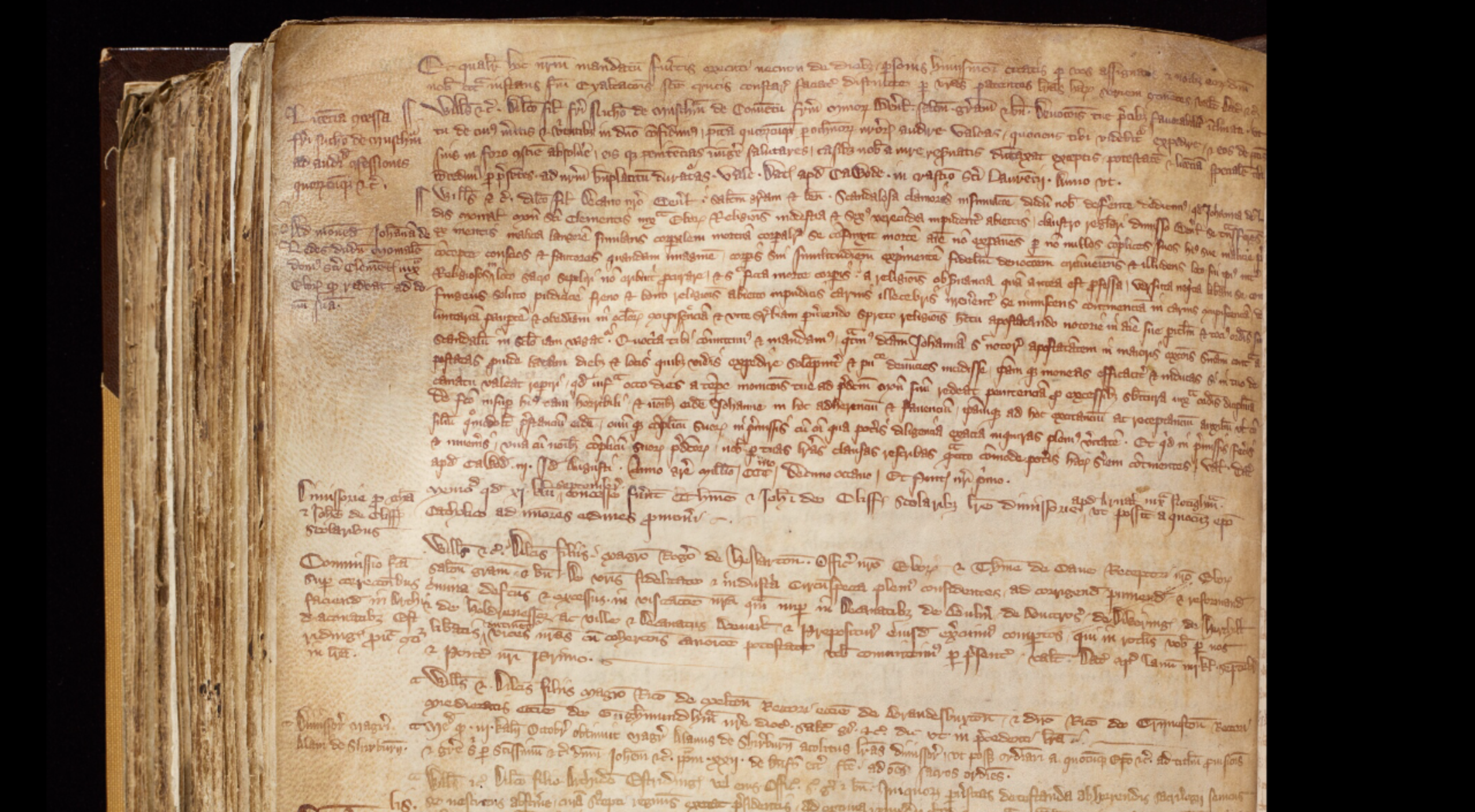

While scouring through a selection of registers from 1304 to 1405, a team of researchers at the University of York found a small note written in the margins of one of the manuscripts. The Latin letters were penned by Archbishop William Melton, alerting the Dean of Beverly that a nun by the name of Joan of Leeds had faked her own death and escaped the house of St. Clement.

“Melton described it as a ‘scandalous rumor’—and I cannot do better than that. In a semi-literate society, rumor and reputation were very important,” says Sarah Rees Jones, a professor and principal investigator on the project, via email. Rees Jones and her team are analyzing this particular set of documents, in which local archbishops detailed their affairs, to better understand Melton’s life and 14th-century England at the onset of the plague.

In his note, Melton’s fury about the ruse cascades off the parchment. He writes, “Out of a malicious mind simulating a bodily illness, she pretended to be dead, not dreading for the health of her soul…” He then goes on to explain exactly how the members of the convent were duped: “and with the help of numerous of her accomplices, evildoers, with malice aforethought crafted a dummy in the likeness of her body in order to mislead the devoted faithful and she had no shame in procuring its burial in a sacred space amongst the religious of that place.”

During the medieval era, many women entered convents while still teenagers. As HISTORY reports, families both rich and poor would often choose a daughter to become a nun, at least in part as an alternative to finding her a husband. Finding work as a woman during this period was also extremely difficult. Life in a convent provided comparatively better living conditions in many situations.

But a life of celibacy and restraint wasn’t for everyone. As Rees Jones notes in her email, “a dislike of the monotony of the religious life,” could’ve caused Joan to skedaddle, or perhaps money was involved. Rees Jones explains that leaving the religious life would have allowed Joan to inherit any money left behind by relatives, which was not allowed under the vow of poverty.

But for now, this is all simply speculation. “In this case, we simply do not know,” says Rees Jones. We also don’t know whether Joan was ever found or if she returned to the convent. That answer may reside scribbled between the fading margins of another register.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook