Sold: Isaac Newton’s Notes About the Bubonic Plague

His scribbles—which mention the curative power of toad vomit—sold for $81,000.

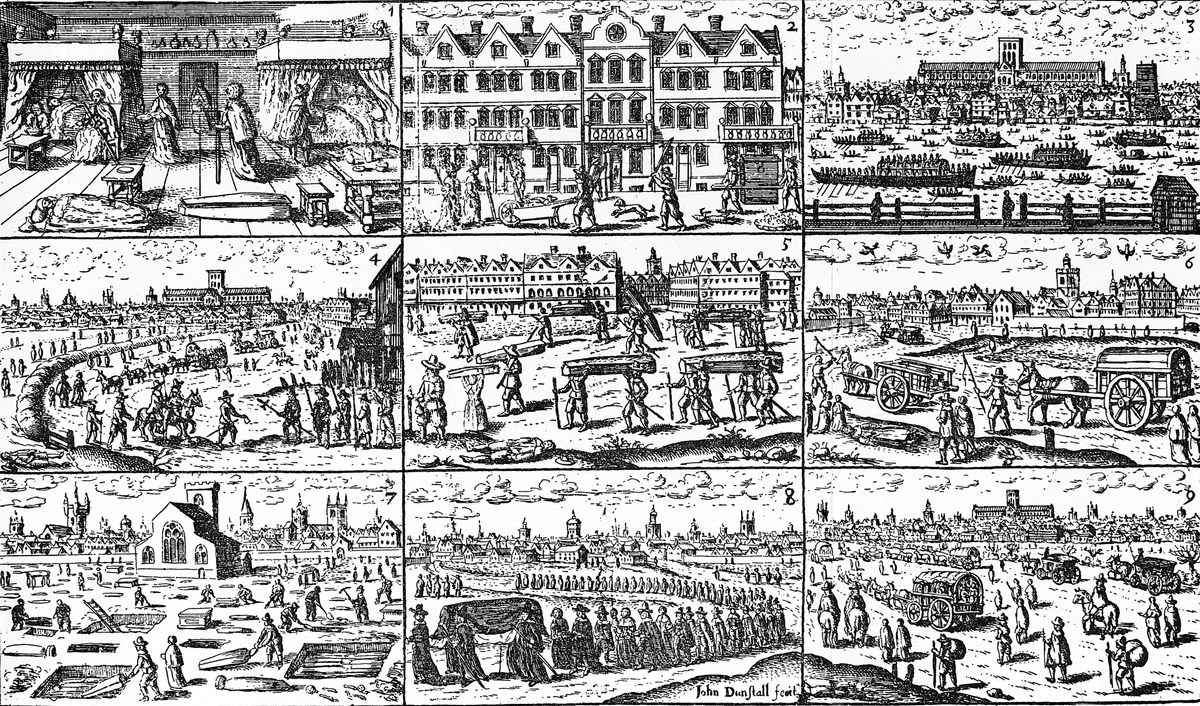

Starting in the spring of 1665, an outbreak of bubonic plague devastated England. The disease was swift and brutal, leaving sufferers woozy with headaches, damp with fevers, and dotted with buboes—firm, tender lymph nodes that could swell to the size of a chicken egg. More than 7,100 Londoners died in a single week in September 1665, according to the National Archives, and by the time the outbreak subsided, around 15 percent of the city’s residents had perished. Those who could escape cities for greener pastures did just that—including brainiacs like Isaac Newton, who was then in his early twenties.

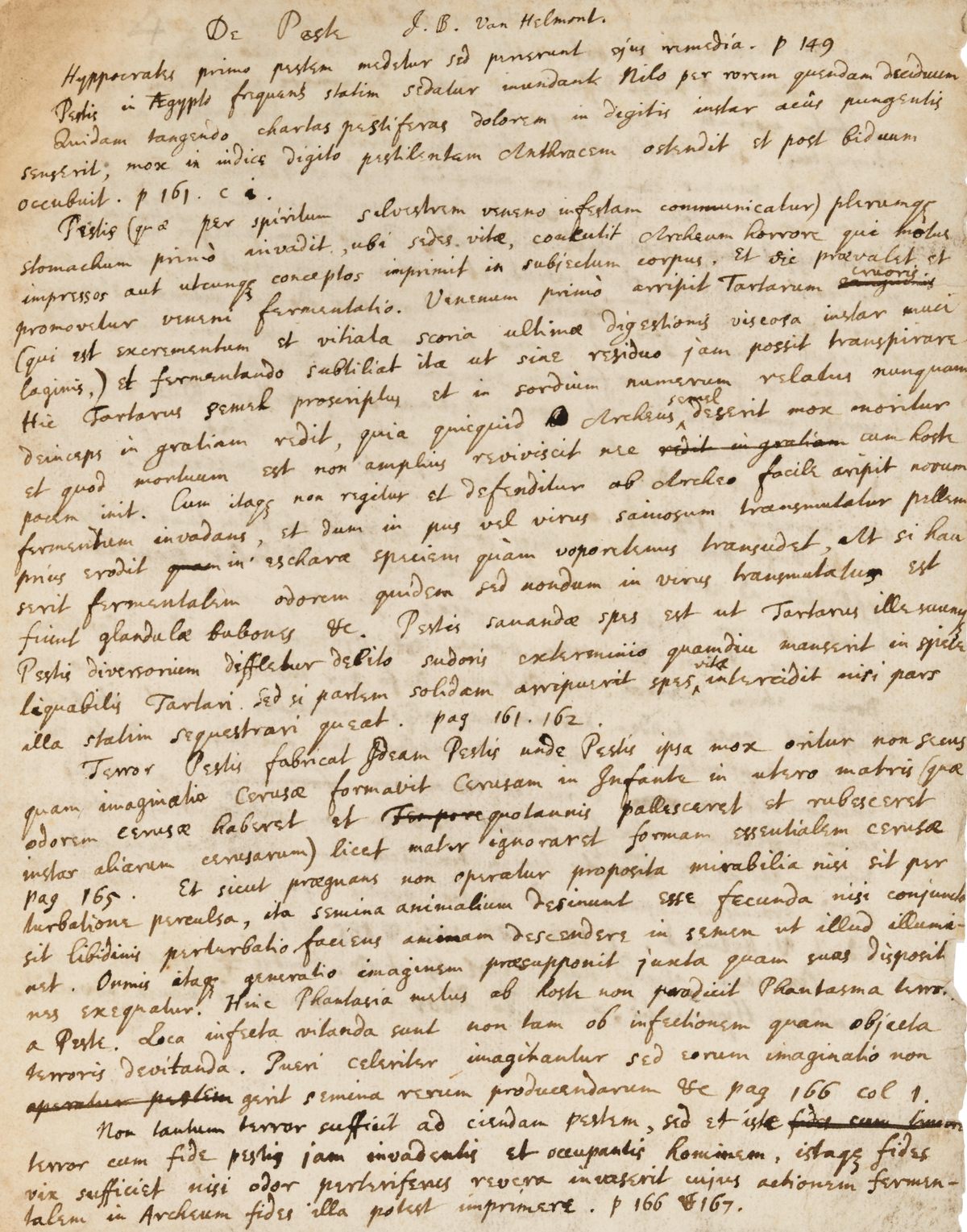

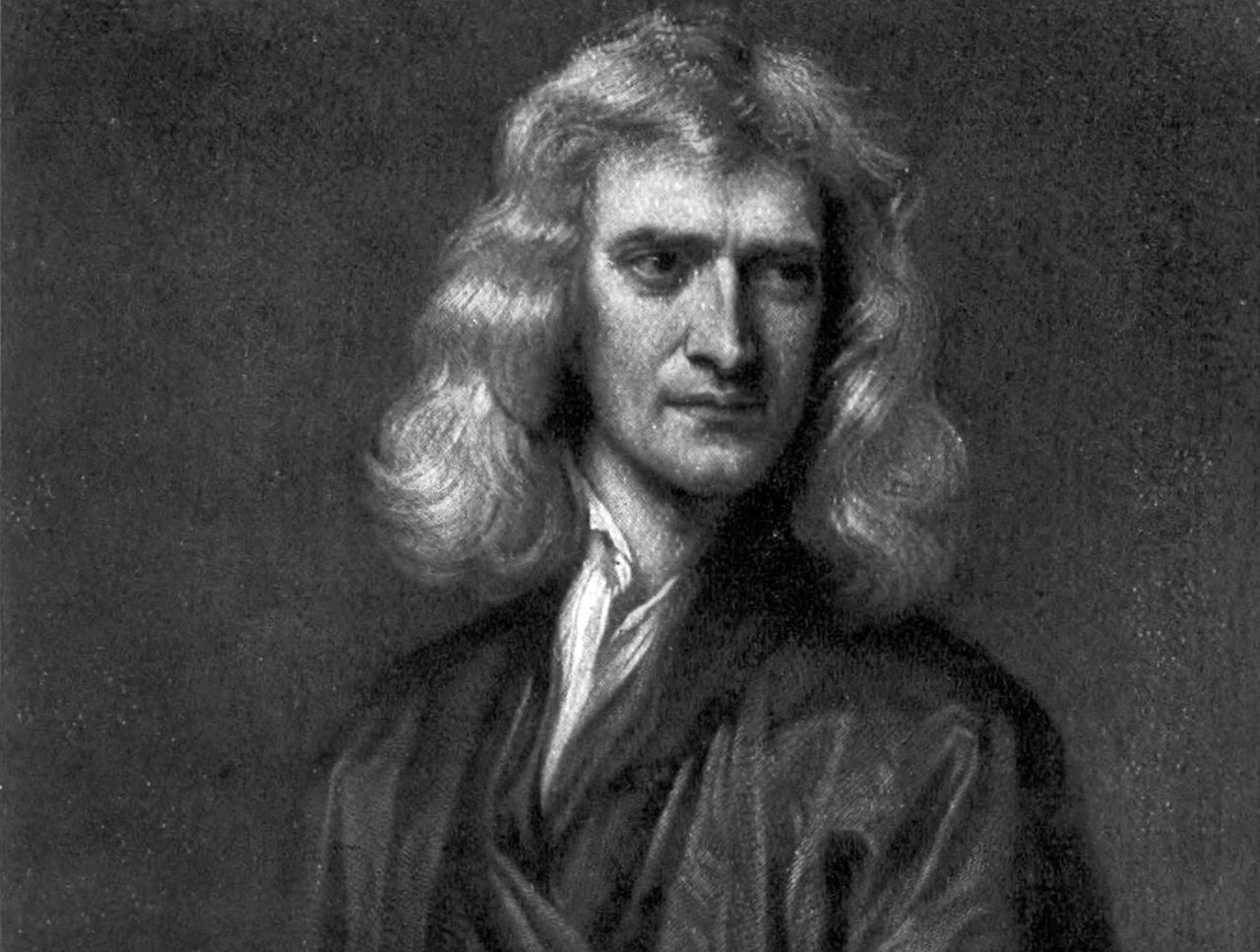

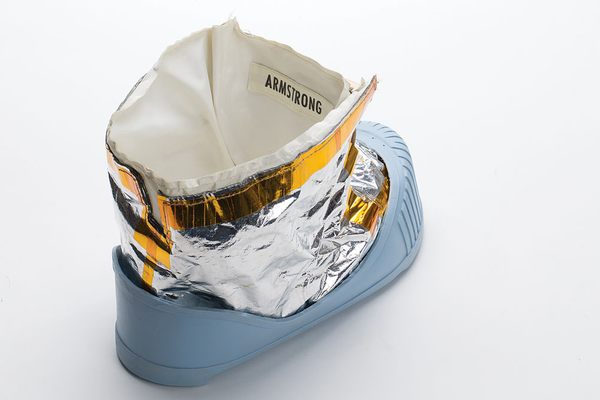

When the outbreak began, Newton fled Cambridge to hunker down at his birthplace, the bucolic Woolsthorpe Manor in Lincolnshire. The landscape was sprawling and verdant, and offered the polymath’s mind ample space for gymnastics. There, Newton spent a lot of time gazing out the window, thinking about apple trees and gravity, prisms and rainbows—but he didn’t totally dodge the plague. At some point, probably after returning to Cambridge in 1667, he picked up a copy of Tumulus pestis, a text on the plague by the 17th-century chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont. A dutiful student, Newton took notes as he read. A two-page manuscript of his notes on van Helmont’s ideas recently went under the hammer in an online auction at Bonhams, commanding more than $81,000.

When the 1660s outbreak emerged, the English government published materials outlining dos and don’ts. Some 17th-century plague-halting tactics will be familiar to people who have spent the last few months versing themselves in social distancing. Borders were closed. Officials tamped down on public gatherings, and some revelry was paused: Justices of the peace, mayors, bailiffs, and others were encouraged to restrict alehouses to the number “absolutely necessary in each City or place.” Ill people were quarantined and shared surfaces were to be thoroughly cleaned—not scrubbed with wet wipes, of course, but “Fumed, Washed and Whited all over within with Lime.”

Other interventions reveal the contemporary uncertainty about exactly how the plague was leaping from person to person. Scientists now know that the disease was caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, transmitted by bites from fleas that hitched rides on rats. But at the time, people cast a wide net of blame. Some residents lit fires to try and blow away bad air. (Children were encouraged to smoke for the same reason, the National Archives reports, though that just fouled the air even more, and gunked up their lungs, to boot.) Officials were instructed to keep an eye out for any shops peddling “unwholsom meats,” “stinking fish,” and “musty corn,” and to halt any pigeons, dogs, cats, or swine wandering the streets or slinking from one house to another.

Helmont’s treatise prescribed some very different tactics. He had first-hand experience with the plague, having been on the front lines in Antwerp when an outbreak erupted early in the 17th century, and some of his advice seems fairly intuitive. For instance, in his notes on van Helmont’s text, Newton observed that “places infected with the Plague are to be avoided.” Other advice is likely more surprising to modern readers. Solid antidotes included sapphire and amber, Newton scribbled—but nothing worked quite as well as toad vomit. Specifically, the vomit spewed forth from a toad that had been “suspended by the legs in a chimney for three days.” Once the toad died, Newton added, the poor creature should be combined “with the excretions and serum made into lozenges and worn about the affected area.” This “drove away the contagion and drew out the poison.”

It may sound puzzling, but “the idea of toad vomit and gemstones worn as amulets and being used as cures was not out-of-place in serious 17th-century medicine and science,” says Darren Sutherland, specialist in books and manuscripts at Bonhams. “These ideas which sound so strange to our modern ears, including toad vomit, were actually squarely situated in the medical traditions and science.” As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, keep practicing social distancing, wearing face masks, and scrubbing your hands. But please note that toad vomit is no match for the virus.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook