Tagging Along With Italy’s Unexploded Bomb–Hunters

There’s less and less for the country’s demining companies to find. Sometimes they pine for the good old days.

Paolo Mennini had gone several months without finding any unexploded ordnance. Not a single bullet. But he had a feeling about this place. We had driven down a one-mile dirt road, past derelict farmhouses and the flat fields south of Mantua, in northern Italy, and walked into a grove to reach a half-collapsed fort.

“Try down there,” he told Andrea Gabrielli, one of his employees. Gabrielli started scouring the ground with a metal detector—a beeping monitor with a long yellow handle, a shoulder strap, and a rod pointing down, roughly the shape of a leaf blower.

The ruins belonged to Forte di Pietole, built by Napoleon in 1808 to defend Mantua, later converted into an armory. On April 28, 1917, the site stored weapons bound for the front lines of World War I when a fire broke out. According to local media at the time, civilians heard explosions pierce the air for four days, crumbling some of the fort’s walls and scattering whatever ordnance hadn’t gone off all around the building. Over time, the site was abandoned and access restricted. Now local authorities were discussing reopening it and the surrounding land as a museum and park, and they were worried it wouldn’t be safe for civilians. Enter Mennini.

Mennini, a slender 52-year-old from Mantua, is the head and technical director of Co.Ve.Smi., one of Italy’s 30-odd private companies specializing in the detection of unexploded bombs.

Some 77 years after the end of World War II, old bombs, ammunition, and weapons continue to disrupt civilian life in Italy (and across Europe). The country recovers some 60,000 pieces of unexploded ordnance a year—shrapnel bombs, grenades, bullets, airplane bombs, made and/or dropped by Italians, Americans, Brits, Austrians, and Germans—according to Roberto Serio, the general secretary of the Italian Association of Civilian War Victims (ANVCG). These finds result in the temporary evacuations of some 150,000 people, while the army attempts to detonate or defuse the old war material.

At the end of 2019, for example, Italian authorities evacuated some 54,000 from the southern city of Brindisi after a construction crew renovating a movie theater uncovered a yard-long British bomb containing some 88 pounds of dynamite. Italian media called it “the biggest peacetime evacuation in the country.” It was one of the about one million pieces of ordnance—some 378,900 tons in total—dropped by the Allies alone in their fight against the Nazi and Fascist regimes, some 10 percent of which failed to go off at the time, according to the U.S. Department of Defense.

There is no clear estimate of how much remains buried, and only the roughest idea where some of it might be. Most lies in the parts of Italy that saw the fiercest combat—the northeast in World War I and central Italy in World War II—but “there aren’t parts of Italy that aren’t affected,” Serio says. “Italy is a wartime dump.”

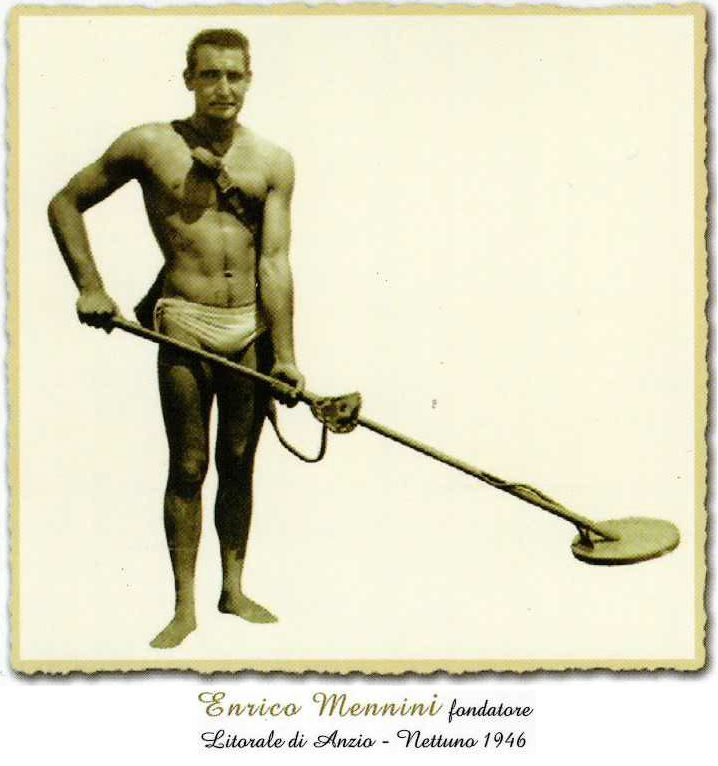

Efforts to demine—a blanket term for the removal of unexploded ordnance—Italy began immediately after World War II. Mennini says that his father, Enrico, who was among the first to volunteer for the cause, was trained by U.S. forces as early as 1945. The company website still displays a 1946 photo of the elder Mennini at age 21, barefoot and in swimming trunks, with a metal detector on Anzio Beach, where the Allies landed to liberate central Italy. At the time, volunteer deminers carried out the whole process: They found, excavated, removed, and sometimes even defused or detonated bombs.

Today, operations continue, but in a more professional manner and under the army’s supervision. But the actual detection of ordnance still falls mostly to private companies. Italian law requires construction firms and local authorities to complete war-remnant risk assessments before excavation for a new building. Unless they can prove there’s only a small risk of finding unexploded bombs, they contract Mennini or one of his colleagues or competitors.

The work is predominantly male, methodical, and surprisingly manual. “We divide the sites in 50-meter-long fields, and the fields in 1.5-meter-wide strips,” said Claudio Orabona, the technical director of CEA Demining, while his team worked a wedge of land near Bologna, between new residential developments, an elementary school, and a rail line—a sensitive target when the Nazis withdrew. As we spoke, a chunky gray plane roared overhead. Orabona said it looked like a military cargo plane—it was late February, the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We speculated it could be part of NATO’s efforts to bolster the eastern front, a reminder that Europe had once again returned to war, even as clean-up of its previous conflicts lingers.

Wailing metal detectors in hand, workers walked up and down each strip in high-visibility clothing, hunting down ferromagnetic interference. “They have to check every signal,” he said, digging first by pickaxe—indeed, the first thing they do when they find metal in the ground is whack away with a metal tool—then by hand, to check and remove even the tiniest trace of iron. Once the ground level is cleared, they use excavators to dig up the soil at regular intervals and a probe again for deeper interference.

The workers wore no special protective equipment. Often, says Andrea Jacopetti Toffano of another demining company, BORD, their only protection is “experience.”

“They are cautious when they dig with their hands,” he says.

Unexploded ordnance can remain dangerous for decades. The mechanical parts of bombs deteriorate over time, but the explosives they contain may not, which can make them more touchy and result in terrible accidents and even deaths—the last one recorded by ANVCG occurred in December 2021.

In 2013, Nicolas Marzolino, then 15, found a red, pear-shaped object in the ground as he prepared to sow potatoes with a couple of friends near Novalesa, a small town at the foot of the Alps, on the Italian-French border. The object was red and silver, wavy and shiny, attractive. Marzolino picked it up and played with it. He shook it close to his ear and joked about it with one of his friends: “It looks like one of your grandma’s cemetery candles.” It turned out to be a Breda Mod. 35 , a grenade issued to Italian soldiers in World War II.

When it went off, it was heard across the valley. “It took away my right hand and my eyesight,” Marzolino says. One of his friends also lost his eyesight. The other, farther away, reported only minor injuries but was so traumatized that he doesn’t remember anything from the incident, Marzolino says. The boys were rescued by gamekeepers stationed half a mile away who heard the explosion and thought it might be poachers. Marzolino has since become a physiotherapist and osteopath, briefly joined the Paralympic skiing team, and visits schools with ANVCG to talk about the risks of mysterious, shiny objects. “If I think about it now, I can almost see the incident as a sort of blessing,” he says. “Yes, I lost a hand, I lost my eyes, and maybe they could come in handy for a few things. But I found much else.”

ANVCG represents some 120,000 war-wounded civilians in Italy, some of whom were hurt long after 1945. But many injuries have been prevented, as millions of pieces of ordnance have been unearthed and detonated under controlled conditions in the decades since, and the law requiring companies to scour construction sites has improved safety. Today, it is relatively rare to find pieces of ordnance, Mennini says, a hint of disappointment in his voice. “More than nine times out of 10 we don’t find anything other than old soda cans,” he says. “Maybe 95 to 98 percent of the time.”

This helps to explain his enthusiasm going into a place likely to hold unexploded ordnance, and why finding one is a cause for celebration among mine-detection crews. Orabona’s team has an unspoken agreement that whoever finds ordnance buys lunch for everyone. “We take pictures of them, like fishermen with their catch,” says Orabona. “You feel that your work is doing good, it’s boring to only pick up waste.”

As soon as they find any ordnance, demining teams are required to freeze on-site activity, call law enforcement, and wait for the army’s bomb disposal service. They are supposed to put up signs warning civilians about the danger, but in practice often skip this stage in the interest of safety—signs tend to attract the curious, as well as thieves.

Civilian companies such as Orabona’s and Mennini’s dabble in trying to identify what they find—make, model, the force that might have fired them. But where deminers like Mennini’s father would handle the ordnance, today the policy is strictly hands-off.

Not everyone is happy with that change. For Mennini, it transformed the job his father used to do, and the business he has come to love. It took away the most “romantic” part, he says. “When I was 25 I would take the van and go in the search—I’d find up to 200 bombs a day and would call a police colonel to blow them up together somewhere,” he says. “Now, what you have sown, they come and reap.”

Toward the end of the morning, as Mennini paced the embankment around the fort’s perimeter, Gabrielli’s metal detector began to beep excitedly. He halted, whipped the pickaxe into the ground, squatted down, and picked something with his hands. “It’s scrap,” he said, tossing it aside with a clang.

Soon after, his team broke for lunch. Over risotto and Lambrusco, they remembered the times when Gabrielli and his dad worked in another section of the fort. It was different then, the atmosphere was different. “It was work, but I had a lot of fun,” Mennini said. “It was a party.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook