How Former Samurai and Farmers Cultivated the First Japanese Apples

Famous fruits, including the Fuji apple, were the result of decades of effort.

In the 1860s, under the threat of colonization by Western powers, the Japanese government undertook an urgent modernization project. Their efforts affected countless facets of Japanese daily life, from the development of a European-style military to smaller changes such as the installation of street lamps.

With a large readership curious about foreign cultures and the new technologies that their nation was rapidly adopting, Japanese publishers rose to the occasion, churning out a vibrant array of books and woodblock prints for the public.

In one such work, the 1873 A Guide to World Customs, author Nakagane Masahira and his Tokyo publisher included an illustration of Newton’s discovery of gravity after he saw an apple fall from a tree. But, what was an apple, anyway? No such fruit was for sale in Tokyo. The publisher obviously thought it would be easier to replace the unknown foreign fruit with something more familiar, such as a Japanese plum.

As illustrators were carving the woodblocks for this image of Newton, the Japanese were just beginning to cultivate the island’s first apple trees. Their efforts would result in a booming domestic apple market, and eventually, the creation of one of the most popular apple varieties in the world: the Fuji.

Nakagane and his Tokyo illustrator should be forgiven for not knowing, but a domestic apple, a distant relative of the apple that so inspired Newton, did actually exist in Japan. Similar to a crabapple, it was smaller than a golf ball, sour, and seen as fit for offering at a Buddhist altar—that is, fit for the dead—but not so much for the table of the living.

But that was soon to change. Apples could last for months in transit, which allowed them to travel from Europe and the United States to Japan. A batch of Western apples arrived via China in the early 1860s, but tasters were unimpressed, deeming the fruit unripe and cottony. Still, it found early adopters. Lord Matsudaira Shungaku of Fukui Domain had them planted at his Edo residence. In 1865, a large shipment of apples arrived in Japan from the United States. “The fruit is nice to look at, and the flavor is so good,” wrote Tanaka Toshio, a naturalist. “People are surprised. They say, ‘Something like this even exists in the world?’ It’s extraordinary.”

This fruit was delicious, but could it be cultivated widely in Japan? Within a few years of Tanaka Toshio taking a bite of his first apple, the young Emperor Meiji and his factions had deposed the last Tokugawa shogun from rule, renamed Tokyo from Edo, and begun their massive Western-style modernization project. To develop domestic agriculture, the Meiji government set aside land, hired foreign specialists, and ordered tons of foreign seeds, plants, and animals.

Prior to a trip to the United States in 1871, Hosokawa Junjirō—who is best known as a legislator, not a farmer—heard from an American agriculturist employed by the Meiji government that apples would be worth growing in Japan. While traveling in the United States on a mission to study the country, Hosokawa acquired a large number of Ralls Janet apples, a variety famously cultivated by Thomas Jefferson. The trees arrived in Japan in 1874, and within the next year, they were distributed to research sites in Hokkaido, northern Honshū, and Nagano. Apples also found their way into farming communities through other pathways. John Ing, a Methodist missionary in Aomori, introduced a different sort of apple to Hirosaki City, and from it, former samurai Kikuchi Kurō cultivated Japan’s first apple, calling it “Indo,” after Ing’s home state of Indiana. This would become the parent breed of a number of popular Japanese varieties, such as the Crispin.

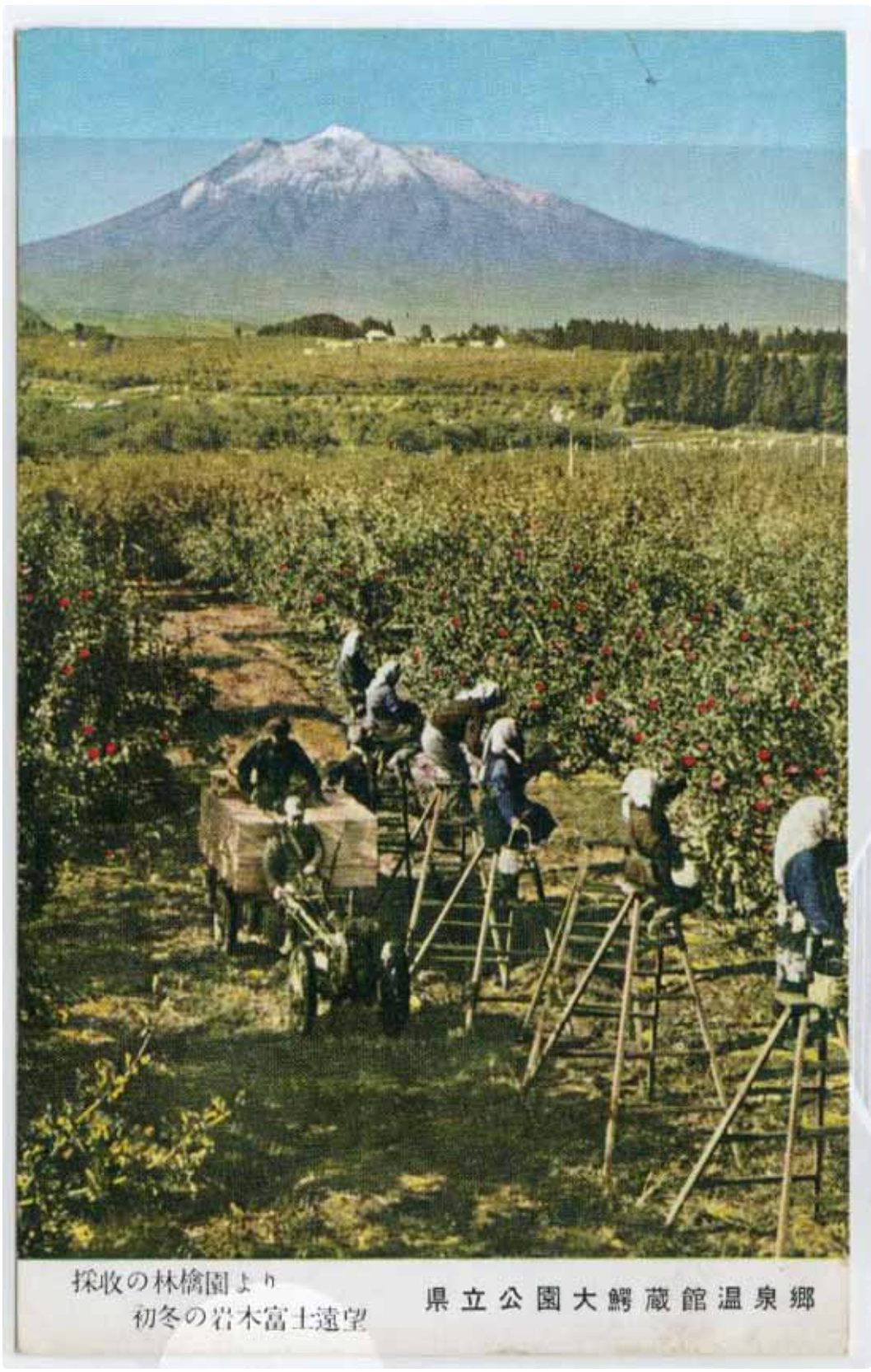

With frigid winters and mild, humid summers, the Aomori and Nagano prefectures turned out to be ideal for growing apples. But, numerous challenges forced farmers to innovate, or risk losing the new crop. In 1877, Kikuchi Tatee, a member of Hirosaki’s prominent local samurai family, was so determined to grow the trees effectively that he set out for the Nanae agriculture test station in Hokkaido to learn about apple cultivation from foreign experts.

In turn, Kikuchi passed on his expertise to horticulturist Tonosaki Kashichi, who would become known as the “God of Apples.” Tonosaki worked tirelessly to support the crop in Aomori, disseminating his research on pest control, pesticides, and pruning. When Aomori farmers became worried about apple branches snapping off in the heavy snow, they created wooden braces for the trees, similar to a kind used in traditional gardens to protect pine trees. When insects and disease threatened their crop, they carefully wrapped each fruit in newspaper and traditional Japanese paper. Before long, farmers were using specially manufactured “apple bags” that can still be seen in Japanese orchards today.

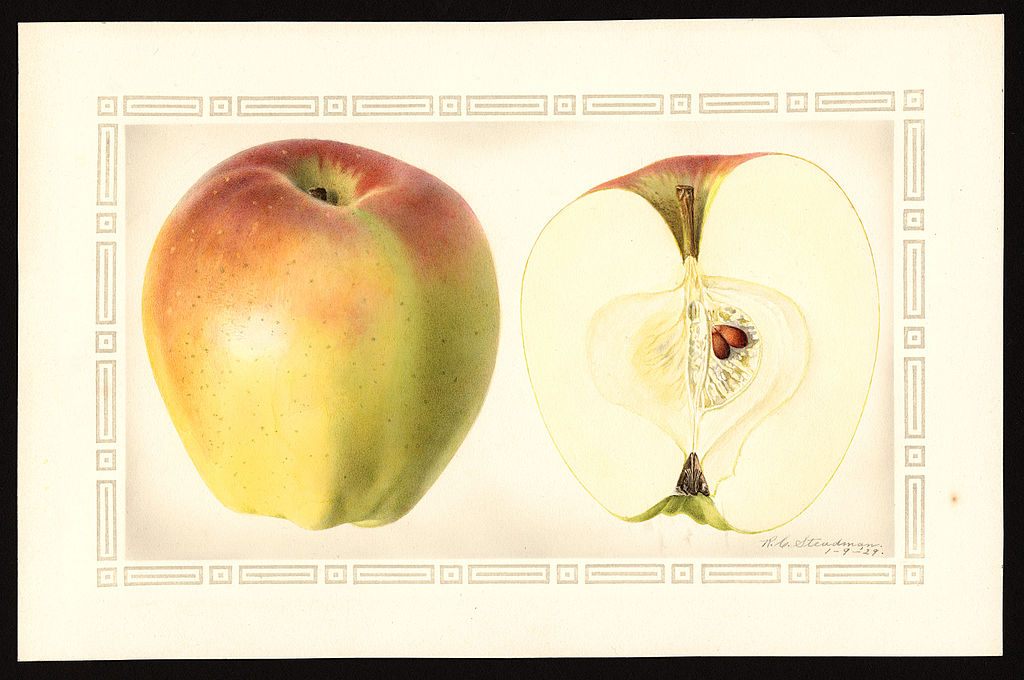

The Fuji came out of a continuous effort in Aomori to breed a better apple. In 1939, researchers in the town of Fujisaki applied Red Delicious pollen to a local Ralls Janet flower pistil. The resulting fruit was sweet and crunchy, with a speckled red skin. They called it “Agriculture-Forestry No.7.”

But the Fuji nearly faded from history. As World War II raged, the apple-growing communities of Japan struggled. In 1941, an early frost wrecked the crop. In 1944, it was a typhoon; the next year it was an ill-timed snowfall that completely wiped out the harvest. Just after the war ended, a man-made disaster ensued in the form of new taxes that knocked the wind out of the apple industry, followed by a price collapse in 1948.

The Fuji apple might have remained “No.7,” lost in local research obscurity, if Japan’s apple region had not come roaring back during the 1950s. Savvy marketers made the apple a symbol of Aomori in advertising campaigns as harvests climbed to historic highs. In 1956, Aomori produced almost 30 million bushels of apples. In recognition of the fruit’s economic and cultural importance, Aomori officials tracked down the oldest apple tree in Japan, located in Tsugaru, and designated it a natural monument in 1960.

Finally, in 1962, the Fujisaki researchers presented “No.7” to the National Apple Name Selection Council. Those present decided to call the apple “Fuji,” not after the famous mountain, but after the town of Fujisaki. The Fuji apple, popular for its crispiness and sweetness, would go on to become the most popular apple in Japan.

Aomori, home to so many of Japan’s apple innovations, currently produces over 400,000 tons of apples annually: the most in Japan, with Nagano in second place. Today, apples remain an important part of their branding and tourism. In Nagano, the local wagyū, or high grade Japanese beef, is famous for coming from “Cows Raised on Apples.” In Aomori, visitors will find a vibrant apple-based tourism industry. Along with apple tours, museums, and famous orchards where guests can pick their own fruit, the region is dotted with memorials to the innovators that made the Japanese apple such a sweet success.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook