Jest Books Were the 16th-Century Version of Insult Comedy

Think Don Rickles crossed with Shakespeare.

Don Rickles, the merciless “merchant of venom” who insulted anyone and everyone during a comedy career that began in the 1950s, passed away in early April. Throughout his years on the stage he was known for his offensive recipe kit of skits that targeted everyone from Mexicans to Jews.

Celebrated though controversial, Rickles was scarcely the first comedian to turn racially insensitive slander into slapstick comedy. In fact, it’s been a practice that dates as far back as 16th-century England, when the first jest book (or joke book) was printed in 1510.

Much of the humor that appears in English jest books is likely lost on a 21st-century audience. The books were written in times of England’s famine, war and starvation, and contained stories that lampooned the weak and needy.

“The terrible famine years of the 1520s and 1530s coincided with a literary craze for jest books,” wrote Linda Woodbridge in Vagrancy, Homelessness, and English Renaissance Literature. Pegged as humorous, jest books were influential for all the wrong reasons—the elaborate and lengthy stories compiled were often written at the expense of immigrants, the poor, or women.

Take, for example, a story published in one of the first English jest books from 1526 called A Hundred Mery Talys*:

“If thou be slow to speake, as one I knew,

Thou wouldst assure thy selfe my counsels true ;

Hee (too late) finding her upon her knees

In Church, where yet her husbands coorse she sees,

Hearing the Sermon at his funerall,

Longing to behold his buriall,

This sutor being toucht with inward love,

Approached neare his lovely sute to move,

Then stooping downe he whispered in her eare

Saying he bore her love, as might appeare,

In that so soone he shewed his love unto her,

Before any else did app[r]och to woo her,

Alass (said she) you labour is in vaine,

Last night a husband I did entertaine.”

Much like it is today, comedy was a white man’s game. In the early 1500s, educated white males realized they could turn a profit by printing popular songs and dances that had previously been shared verbally. The books sold for cheap, meaning the subjects of their mockery could easily afford them.

Intellectuals were rarely the subjects of these jests, but instead were the men behind them. Printing, manufacturing, and crafting a ballad took organizational skills, yes, but also an education — something second-class citizens lacked.

Many educated men would publish these jest books under pseudonyms or anonymously, taking names from actors or clowns, “so as to make the books popular and increase sales,” according to A Brief History of American Jest Books by Harry B. Weiss; over time, these men’s involvement became minor blips on their resume. Thomas More, the philosopher and famed author of Utopia, got his start with the jest book A Merry Jest how a Serjeant would Learn to Play the Friar, though it was dismissed as mere experimentation and inferior once some of his greater works appeared.

The slow decline of English jest books in their original, discriminatory glory was due in part to an English law passed in 1549 that stopped production of pamphlets that had an “evil zeal for lucre” and were “covetous of vile gain.” By that time, however, the concept of the jest book had made its way across the pond to colonists settling in America.

For many years, Americans imported English jest books. It wasn’t until 1787 that the first American-printed jest book appeared in the pamphlet titled A Collection of Funny, Moral, and Entertaining Stories and Bon Mots issued by New Haven-based printer and publisher Daniel Bowen. That started a wave of American jest books, with several appearing that first year—though much of the humor was still patterned with an English slant, translated poorly by publishers for an American audience.

“Substitution, in some cases, of the names of American personages and places failed entirely to make them American jests and the supposedly humorous accounts are not associated with the fashion, beliefs, and customers of America,” wrote Weiss in Brief History of American Jest Books. It wasn’t until the mid 1800s that American lingo was integrated into the printed comedy scene.

An example, from Bowen’s Collection of Funny, Moral, and Entertaining Stories and Bon Mots:

“A Bill was once brought in, in the assembly of a neighbouring State, for the purpose of organizing the Militia. A venerable old man arose and opposed the Bill, for, says he, our Militia have good Drum’s and Fifes, and therefore I think it needless these hard times to be at the expence of purchasing them Organs.”

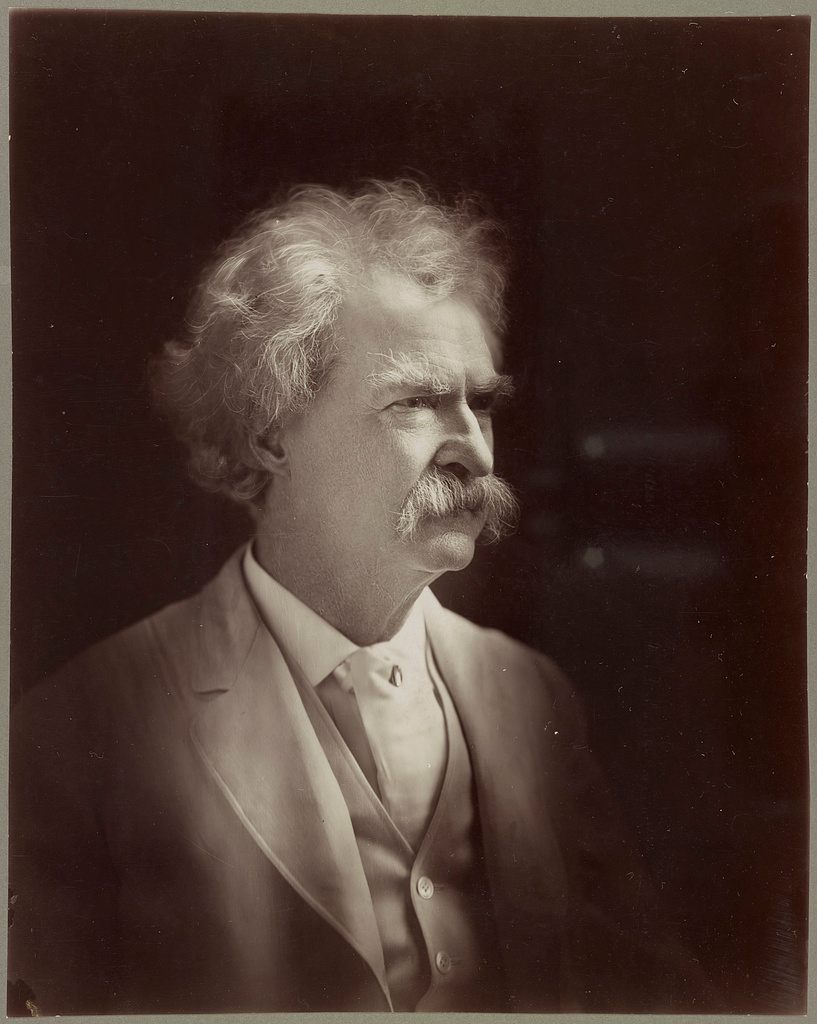

The most famous jest book author in America would come a few years later; Samuel Langhorne Clemens’ earliest work was in the form of short stories and jests, though he later became known for his novels that captured the Americana spirit—written under the pen name Mark Twain.

Like their predecessors, American jest books indicated the ethnic divide between two groups; in this case, the colonists, and everyone else. Not surprisingly, English colonists immediately crafted their impressions of Native Americans in disparaging language, a testament to the racial discrimination between the settlers and anyone who got in their way.

“Along with blacks and Native Americans, the Irish were the most frequent targets of ethnic humor,” writes Robert Secor in the section “Ethnic Humor in Early American Jest Books” from the 1993 collection of essays A Mixed Race: Ethnicity in Early America. “However, whereas the other two groups were objects of ethnic humor largely because the new Americans who told the jests were structuring their attitudes toward them in the New World, the Irish were butts of ethnic jests largely because the American settlers brought their stereotypes with them.”

More often, as the jest books became popular in America, women were the core targets. One tale described in The Universal Jest Book: Being a Collection of Anecdotes, printed in 1829 by Geo. G. Sickels, victimized two of the most commonly ridiculed: immigrants and women. In the story, a Frenchman is chastised for speaking poor English when he misunderstands a woman and begins kissing her without her consent for the satisfaction of his fellow lads. The jest:

“A French gentleman, totally unacquainted with the English language, being introduced to a circle of young ladies and gentlemen in Boston, after the usual compliments had passed, seated himself along side of a beautiful young lady ; and being deprived of the satisfaction of conversing with her, he seized her by the hand—she requested him to be easy—which he mistook for the word baissez (kiss me) and began kissing her, to the great mirth of the whole company.”

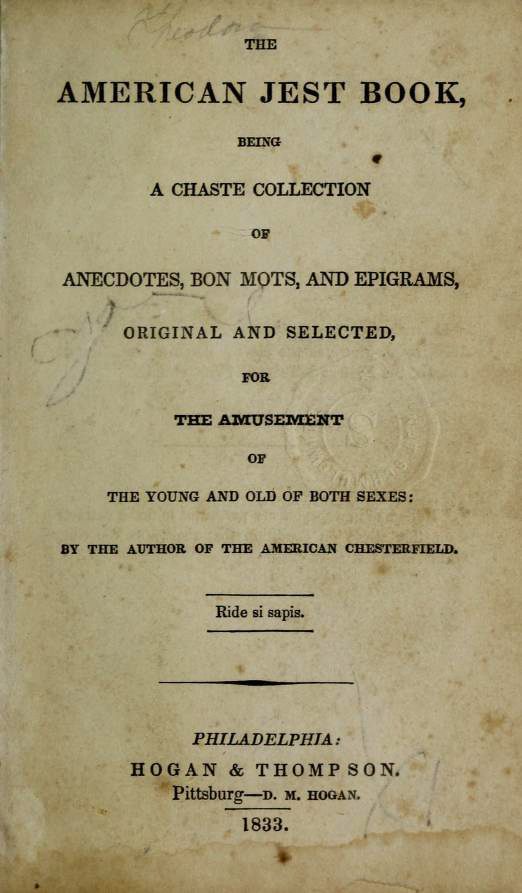

It took about a century, but eventually American jest books got tamer. In the introduction to The American Jest-Book, which was published in 1833, the authors felt it necessary to explain the type of writing included. “Indeed, not a single volume, in the form of a Jest Book, has ever yet been published, that was fit to be read by any female without a blush, nor by young persons, of either sex, without some injury to their morals … The present volume professes to be superior, in every respect, to any of the kind that has ever yet been published.”

Not long after The American Jest-Book was published, the jest book saw a steady decline and eventually became obsolete. Though their legacy, as seen in Rickles’ popular standup skits, lives on.

*Correction: The story originally stated that Shakespeare penned some jesting words that were published in A Hundred Mery Talys. As the book came out before he was born, this is impossible. Shakespeare did, however, appear to reference A Hundred Mery Talys in one of Beatrice’s lines from Much Ado About Nothing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook