The Cowboy Cartographer Who Loved California

Jo Mora poured the state’s whole history—and his own life—into his incredibly detailed, whimsical maps.

Joseph Jacinto Mora knew all the dogs in Carmel-By-The-Sea, California. He knew Bess, a friendly brown mutt who hung out at the livery stables. He knew Bobby Durham, a pointy-eared rascal who, as Mora put it, “had a charge [account] and did his own shopping at the butcher’s.” He knew Captain Grizzly, an Irish terrier who went to town with his muzzle on and invariably came back carrying it, having charmed a kind stranger into taking it off.

If you spend time with Mora’s map of the town—which was first printed in 1942—you’ll know the town dogs of that era, too. They’re all stacked in a column on the right side, lovingly described and illustrated, and looking as natural as those items you’d be more inclined to expect on a map: streets, land masses, the compass rose. On this particular map, those elements aren’t so typical either: the streets are strewn with tiny houses, and both the land and sea are peppered with busy people. The compass rose is rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise, and—as befits an artist’s town—is helmed by a painter, a performer, a writer, and a musician.

Such is the way of a Jo Mora map. Over the course of his life, the “Renaissance Man of the West,” as some have called him, packed history, geography, and personal details into a series of maps of different parts of California. Although well-known in his time—“Mora has produced works of art which have told their story to more persons, probably, than have the works of any other Californian,” columnist Lee Shippey wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 1942—he has largely fallen out of the public consciousness. But a few minutes with one of his maps plunges you back into his era, and his own worldview.

Mora was born in Uruguay in 1876. When he was four years old, his father, the sculptor Domingo Mora, moved the whole family to Massachusetts. He went to art school in New York City—a place full of “precipitous sided canyons and underground burrows,” he later wrote—and worked as an illustrator for the Boston Herald, drawing scenes from the day’s news.

Throughout, “he was really curious about the American West,” says Peter Hiller, the Collection Curator of the Jo Mora Trust, and the author of an upcoming biography of Mora. Even as he was getting his degree and amassing an East Coast portfolio, he was spending long stints on the other side of the country. He worked as a cowboy in Texas, and rode on horseback from Baja, Mexico up to San Jose. He lived in a Hopi and Navajo community for two-and-a-half years, learning to speak both languages, taking photographs, and painting precise watercolors of Kachina dances. By 1907, he had officially moved to California, settling in Mountain View with his wife, Grace Alma Needham.

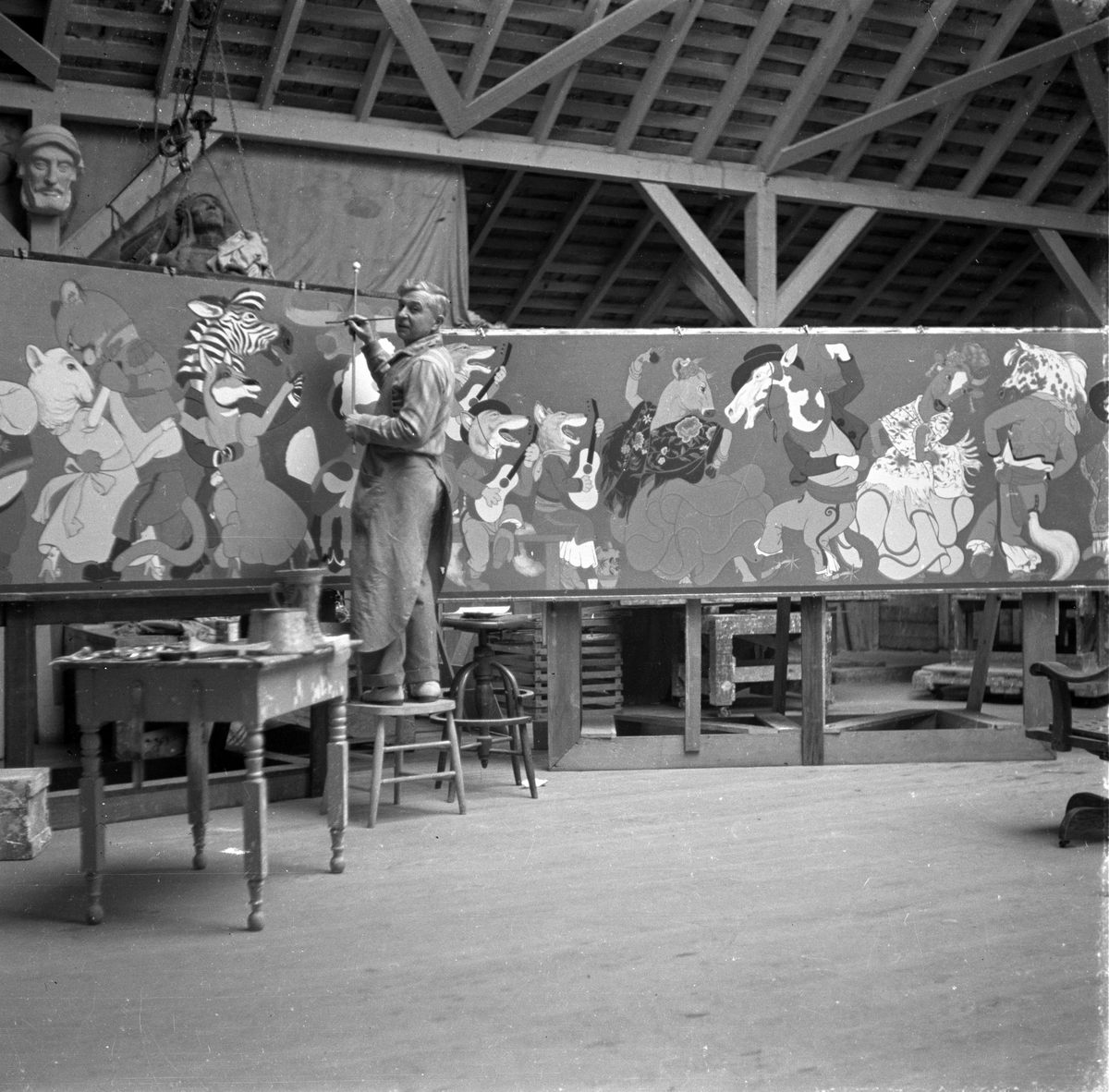

Over the course of his career, Mora explored a number of different mediums, including sculpture, painting, and coin design. “It’s almost easier to list what he didn’t do,” says Hiller. But beginning with his first published map—of the Monteray Peninsula, commissioned as part of a local history book—cartography came particularly easily to Mora. “I’ve had this feeling from talking to Jo’s son Joey that [the maps] were almost spontaneous,” says Hiller. He would sketch a draft out in pencil, and then redraw it in black ink, on a large, heavy board. It would then be shrunk down during the printing process.

In final form, the maps are flamboyant and dense, giving an impression of near-limitless detail. “They’re almost like books,” says Hiller. “You look at a part of them and set it aside, and then come back the next day and look at a different part.” When he’s done exhibitions of Mora’s work, he adds, the maps in particular are “like magnets … People just get totally absorbed in looking at them.”

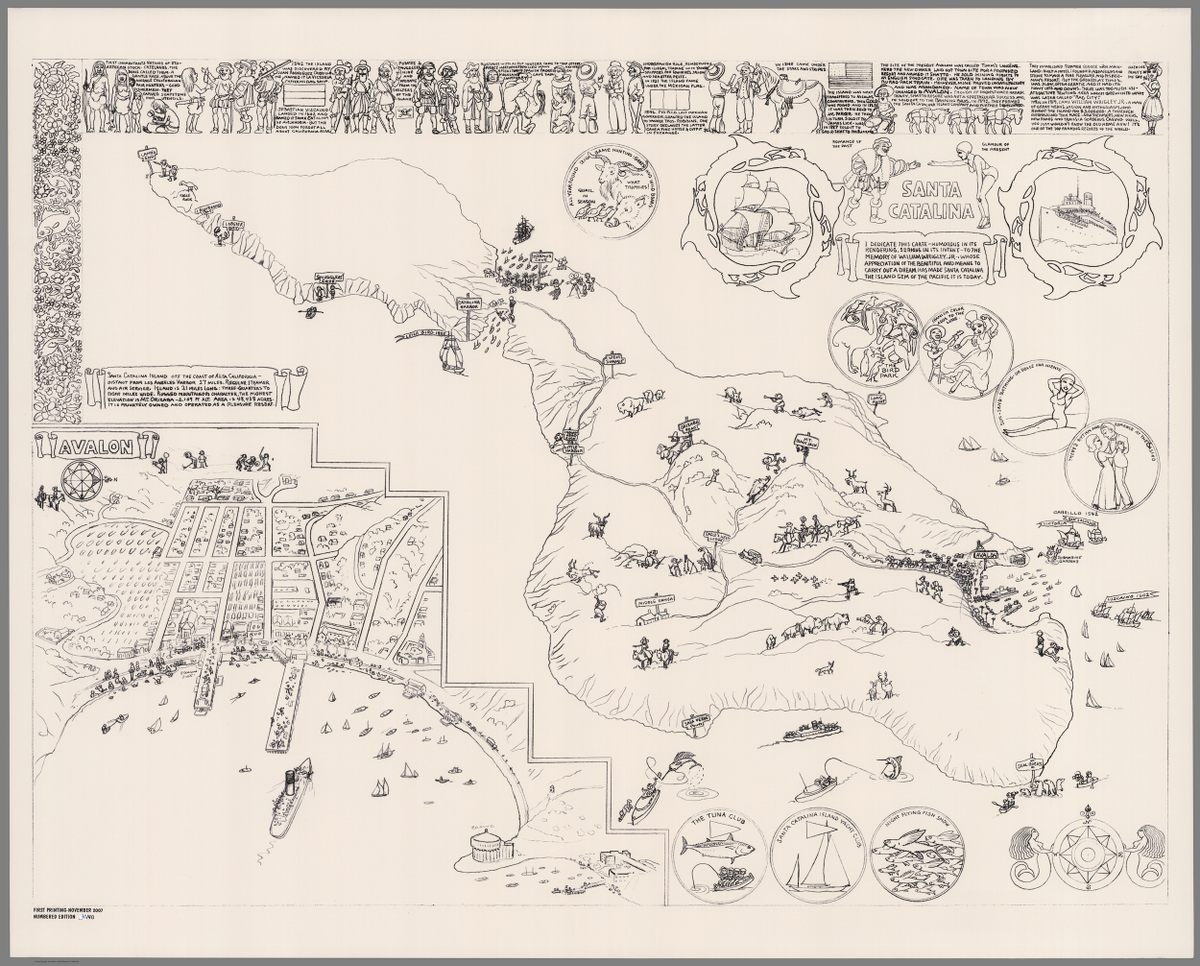

Mora referred to his maps as “cartes.” (“I think it’s based on the derivation from ‘cartography,’ and there may be a French component to it,” says Hiller.) But stylistically, they belong to a genre called “pictorial maps”—detailed geographical illustrations that privilege engrossing storytelling over strict accuracy. Historians trace this trend back to the Wonderground Map, a 1914 map of London created by a graphic designer named Leslie MacDonald Gill. By the time Mora was making his, they’d become quite popular, used to advertise travel destinations or depict recent events.

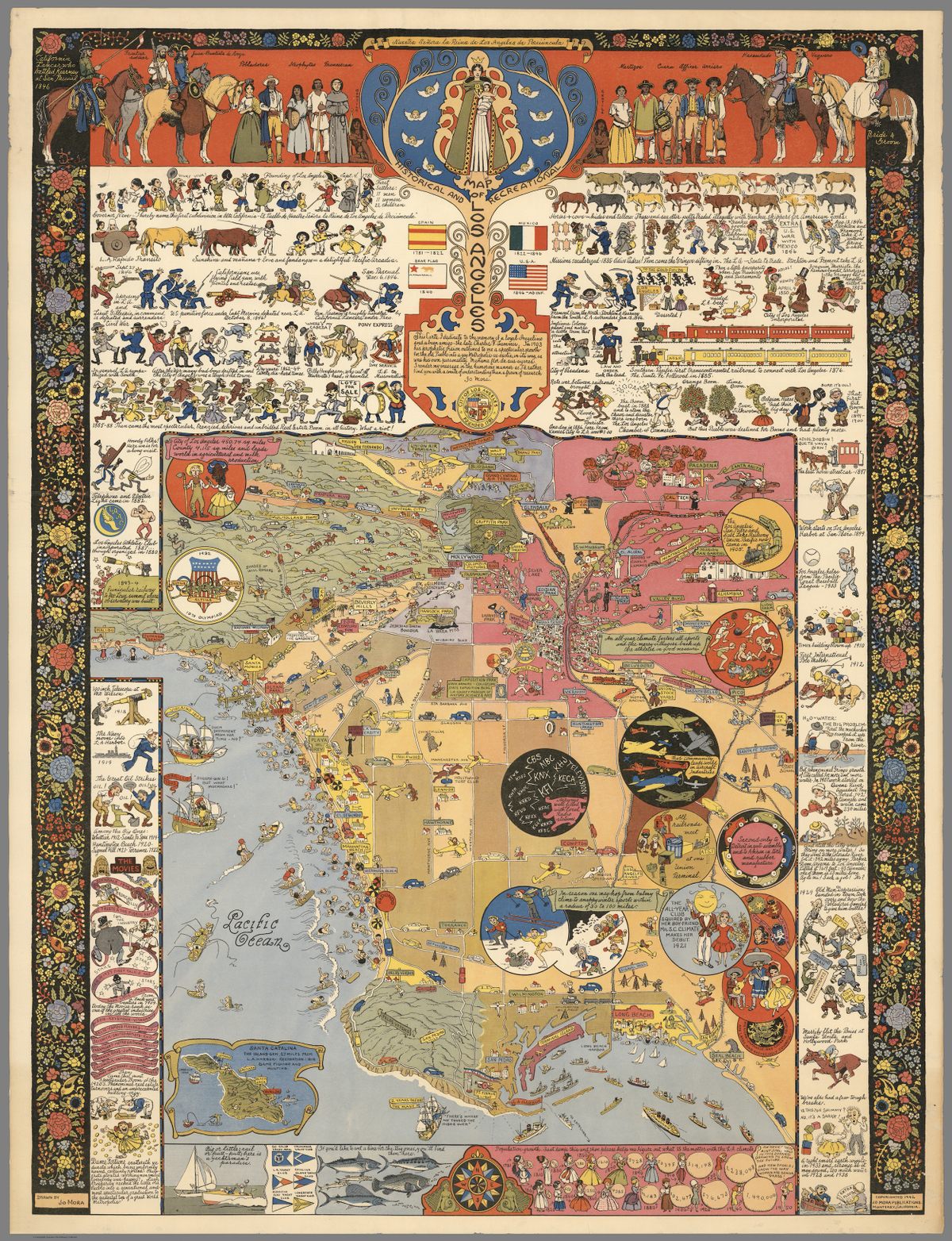

Mora’s experience and sensibility lent themselves well to the pictorial map. But even as he worked within the genre, his particular values and obsessions often stuck out. “[The maps] tell stories about the history of California,” says Hiller. “He acknowledges the different eras,” and the groups of people who shaped the state: Native Americans; Spanish missionaries; Anglo prospectors. At the same time, they’re often steeped in the particular moment, full of inside jokes and local color. As Mora himself once put it, “I render my message in the humorous manner as I’d rather find you with a smile of understanding than a frown of research.”

Take his 1942 map of Los Angeles, pictured above. The top strip is dedicated to detailed illustrations of Franciscan friars, and vaqueros on horses. They appear almost somber compared to the middle, which is a riot of visual puns and whimsical situations. A lion dances in the Griffith Park Zoo, and the Hollywood Bowl is a giant dining bowl, with two spoons. For the railroad rate wars of the 1880s, two bug-eyed train engines fight with boxing gloves.

To illustrate the city’s increasing popularity, he draws a series of women, each dressed in the style of their era, inflating massive balloons with population numbers on them. “Aw heck!” reads the balloon of the 1950s woman, who is in her underwear, or perhaps a bikini. “There ain’t space enuf in this derned drawing to show the future. And how should I know the way women are gonna dress!”

As such a joke indicates, if you engage in the kind of close reading that the maps demand, you’ll find that they are fully of their era in another way, too. On the Carmel-By-The-Sea map, a drawing of a Native American is accompanied by a racist caricature of Native language. Few black people appear on his maps, and when they do, they are generally in service positions. Hiller says “he meant no disrespect of course, but he did a couple of times dwell in what you would call cliches. Social cliches.”

Some maps were commissioned, usually by businessmen who had a stake in drawing people to a particular area. “[Mora] was sort of like Gumby,” says Hiller. “He was so flexible that if a project came his way, and he didn’t know how to do it, or to execute it for the client, he would figure it out.” In 1928, for example, Marston’s Department Store hired Mora to draw a map of San Diego, which ended up a seamless assemblage of facts about the store and the city as a whole.

Others were dreamed up by Jo’s son and business partner, Joey. “Joey suggested a lot of subjects over the years, and Jo would just sit down and do the maps,” says Hiller. Joey would then go sell them at trading posts and gift stores. One of these—a 1931 map of Yosemite National Park, full of mini-wildlife and tourists getting into mishaps—was particularly popular. “There is so much of grandeur and reverent solemnity to Yosemite that a bit of humor may help the better to happily reconcile ourselves to the triviality of man,” Mora wrote on the map’s legend.

Sometimes, that humor came from shrinking himself. By studying the journals Mora kept during his own trip to Yosemite, Hiller has pinpointed two tiny Jos on the map—one taking photos at Nevada Falls, and one drinking from a canteen beneath Sentinel Dome. “Selling those maps got the family through the Great Depression,” says Hiller. “People were willing to spend 50 cents on them at a time when money was hard for everybody.”

Mora died in 1947, having made about a dozen maps. One of his last was the one of Carmel-By-The-Sea, where his family ended up living. Perhaps more than any of the others, you can see his life in this one. Hiller is convinced that the two tiny figures riding horses on the top left side are his children, Patty and Joey. And then there’s that column of town dogs—one of which Jo must have known particularly well. “Mike Mora could climb a rung-ladder like a chimney sweep,” he wrote, over a drawing of a smiling, shoe-wearing canine. It’s his map—he’s allowed to immortalize his dog.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook