The Hanging Cage That Held an Infamous Québec Murderess

It had been all but forgotten for most of the 20th century.

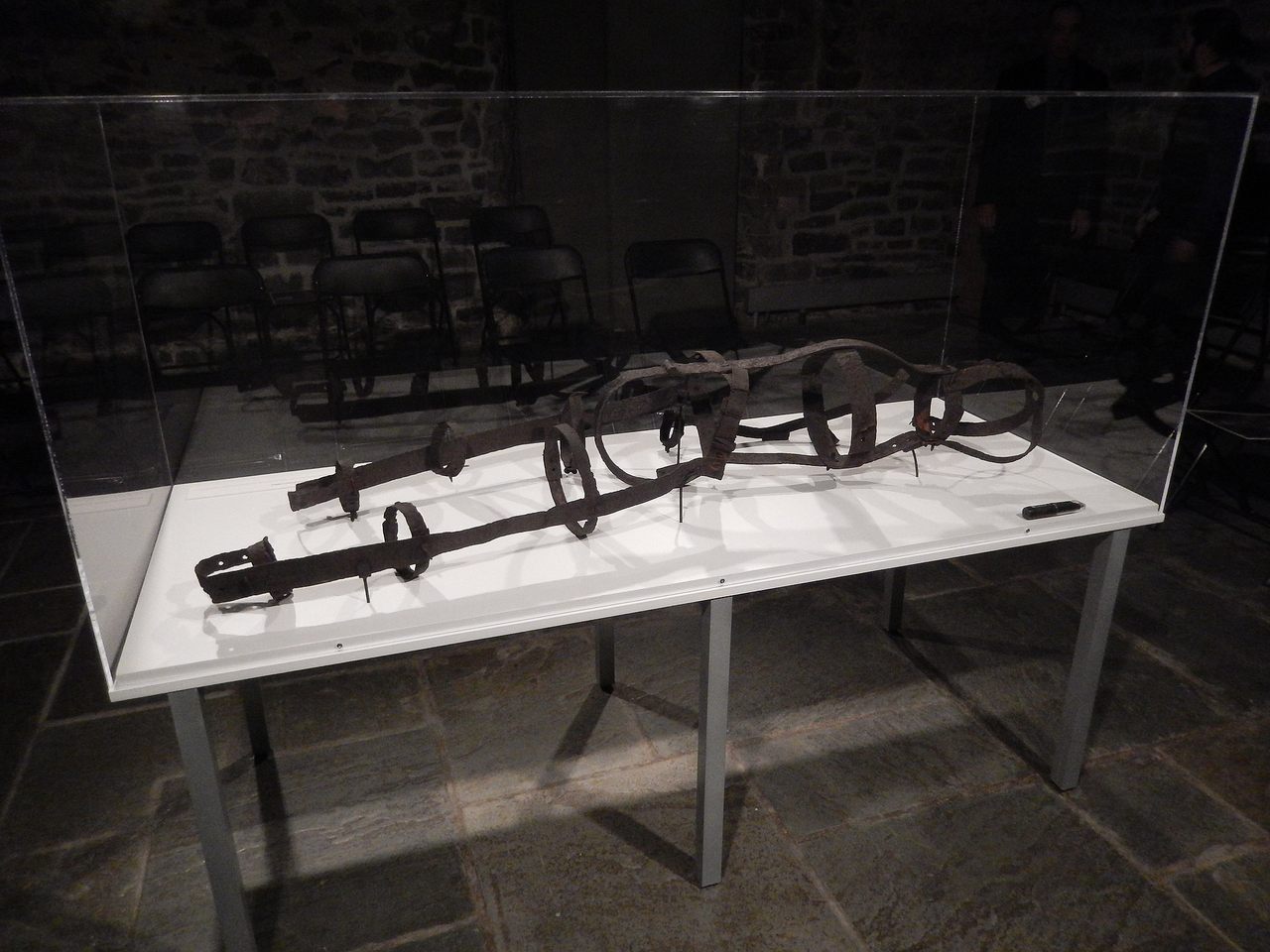

For centuries, the ghost of Marie-Josephte Corriveau has been haunting the cultural consciousness of Québec, Canada. To many, the legend of “La Corriveau” is a ghost story, of a woman hanged for murder, her corpse put on display as a gruesome warning. But the story of La Corriveau and the gibbet in which she was hanged are based on real historical events, and after over a century away, the actual cage has made its way back home. As a result, Corriveau’s legacy has lately been shifting from folk tale to historical tragedy.

Marie-Josephte Corriveau was born in 1733, in what was at the time, a country called New France, which, by the time of her death, was controlled by the British. “The British forces were completely unorganized,” says Sylvie Toupin, a curator at Québec’s Musée de la Civilisation, which currently holds Corriveau’s infamous gibbet. “There were many tensions because it was a new government, and the people weren’t happy with what was happening.” Ultimately, Corriveau would become a dire symbol of this frustration and disorganization.

At the age of 16, she was married to a local farmer. He died in 1760, leaving her alone with three children to care for. However Corriveau quickly found another husband, marrying Louis Étienne Dodier, another farmer from her parish, less than two years after the death of her first husband. But he wasn’t long for the world either.

Dodier turned up dead in January of 1763. Corriveau and Dodier’s marriage was the talk of the town, and not in a good way. Her father, Joseph Corriveau, had a number of very public fights with Dodier over property and business dealings, and Marie had petitioned, unsuccessfully, to leave her husband, on the grounds that he was physically abusive.

So when Dodier was found dead in their barn, initially thought to have been the result of being kicked in the head by a horse, the rumors about town soon turned the focus of the investigation to murder. Dodier’s wounds were reexamined and determined to have been caused by something closer to a pitchfork than horse hooves, and both Joseph and Marie were accused of murdering the man.

After an initial trial before the military, Joseph was found guilty of Dodier’s murder and Marie was found guilty of being an accomplice. But when Joseph was sentenced to hang for his crimes, he cracked, telling the court that in fact his daughter had committed the murder, and that he hadn’t turned her in only because trying to keep her from the gallows. When questioned about this shocking turn of events, Marie finally admitted to killing Dodier with a hatchet.

Likely embarrassed by the initial wrongful conviction, and possibly influenced by fresh questions about her first husband’s death that were now being whispered about by locals, the British authorities in charge of the province at the time held a speedy, cursory second trial. “It was a military trial, because they were not equipped to hold a civil trial,” says Toupin. “They surpassed their given powers because the king in England did not give the final approval.” They sentenced Marie not only to hang, but for her body to be gruesomely displayed in a metal gibbet as a warning. She was hanged in April of 1763, and her body was placed on public display for about five weeks in nearby Pointe Lévis.

“They wanted to give an advertisement to the population with this hanging in the cage,” says Toupin. “It was unusual because this tradition didn’t exist anymore in France, but the British still used it, so it was a new thing for us, and for us an important political symbol. It’s still in our memory, because what they did was unfair.” Corriveau’s extreme sentence, both shocking and cruel, cemented her story in the local history and culture.

Eventually Corriveau’s body, metal gibbet and all, were taken down and buried in an unmarked grave in a Pointe-Lévis churchyard. And for almost 100 years, that’s where she stayed, her story slowly taking on mythic dimensions.

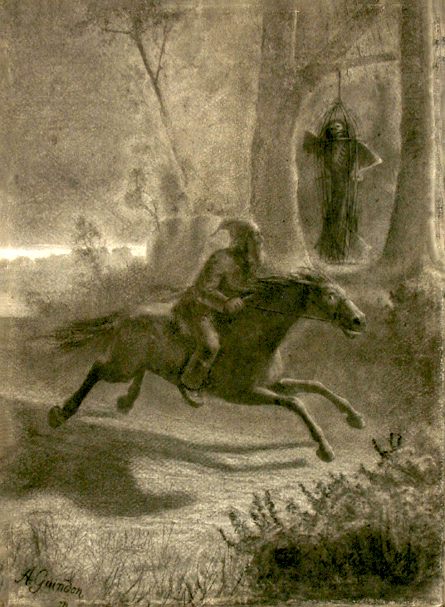

Fueled by her sensational, shocking trials and not a small amount of reactionary demonizing of women, the story of La Corriveau evolved, sometimes gaining supernatural flourishes. As the legend grew over the next several decades, her number of dead husbands rose to seven and there were whispers of witchery, or that she was descended from a famous poisoner. Her popular image became a macabre reflection of her final fate, a skeleton in a hanging cage that would appear to terrorize residents. “People tried to understand that [event], so they made stories,” says Toupin. “La Corriveau is still living among us because many people know the story.”

Then in 1851, the gibbet in which she was buried, her “cage,” was unearthed from the churchyard where it was interred. “She was not in the cemetery. They decided to enlarge [the cemetery] and they found the cage just by luck,” says Toupin. This discovery no doubt injected the folktales with even more life. Versions of La Corriveau began to appear in Canadian literature, and soon she had become something of a cultural institution. But her cage wouldn’t remain in Canada for long.

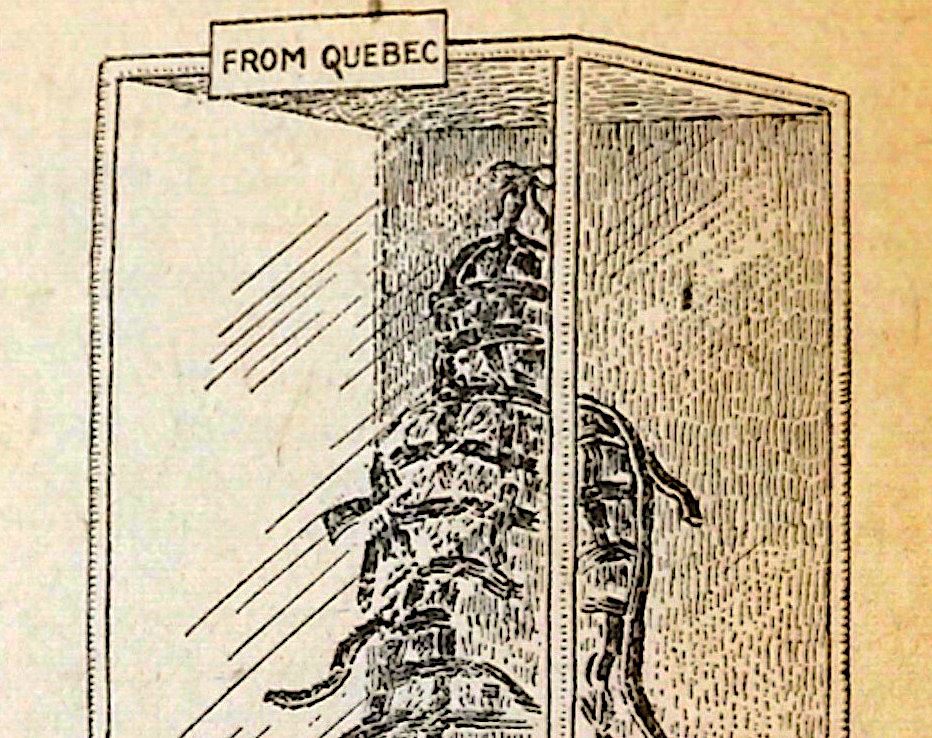

Within months of being dug out of the ground, the gibbet was exhibited in Montréal, Lévis, and Québec City, before ending up in the hands of P.T. Barnum, who put it on display as a curiosity in his New York museum, in August of 1851. It had a simple plaque that read, “From Quebec.”

From there the cage passed to the Boston Museum in Massachusetts, around 1869. According to dates provided by Toupin, which have only recently been unearthed, the cage then passed to the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts, around 1899, and was put on display at least once around 1931.

According to Dean Lahikainen, the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Art at the Peabody Essex Museum, the modern incarnation of the Essex Institute, it’s unclear precisely how long the Institute had the cage on display, but it stayed in their collection for over a century.

In the early 2010s, members of the Lévis historical society rediscovered it at the Peabody Essex Museum, after it had been all but forgotten for most of the 20th century. Working with the museum, Corriveau’s cage was repatriated to Lévis for a special exhibition in 2013. According to Lahikainen, the directors and trustees at the Peabody Essex Museum then donated it to Musée de la Civilisation in Québec, where it remains to this day.

The legend of La Corriveau is still a well known folk tale in Québec, and versions of her story have been turned into a number of books, operas, and more. But thanks to the return of the gibbet in which she met her final fate, the legends and stories are hardening into cold history. In fact Corriveau’s gibbet is still being tested and studied to see if they might even be able to pull DNA from it. As Toupin says, “Now it’s real, it’s there, it’s scientific.”

This article was updated, with minor edits, on October 15, 2020.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook