For Centuries, People Thought Lambs Grew on Trees

The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary puzzled scientists and philosophers.

Imagine you’re strolling through the woods in Central Asia, in a region formerly called Tartary, sometime during the Middle Ages. As you adjust your woollen cloak, you spot an eye-catching plant. A long, swaying stalk juts out from the ground, bearing a bleating, life-sized lamb hovering a few feet off the ground.

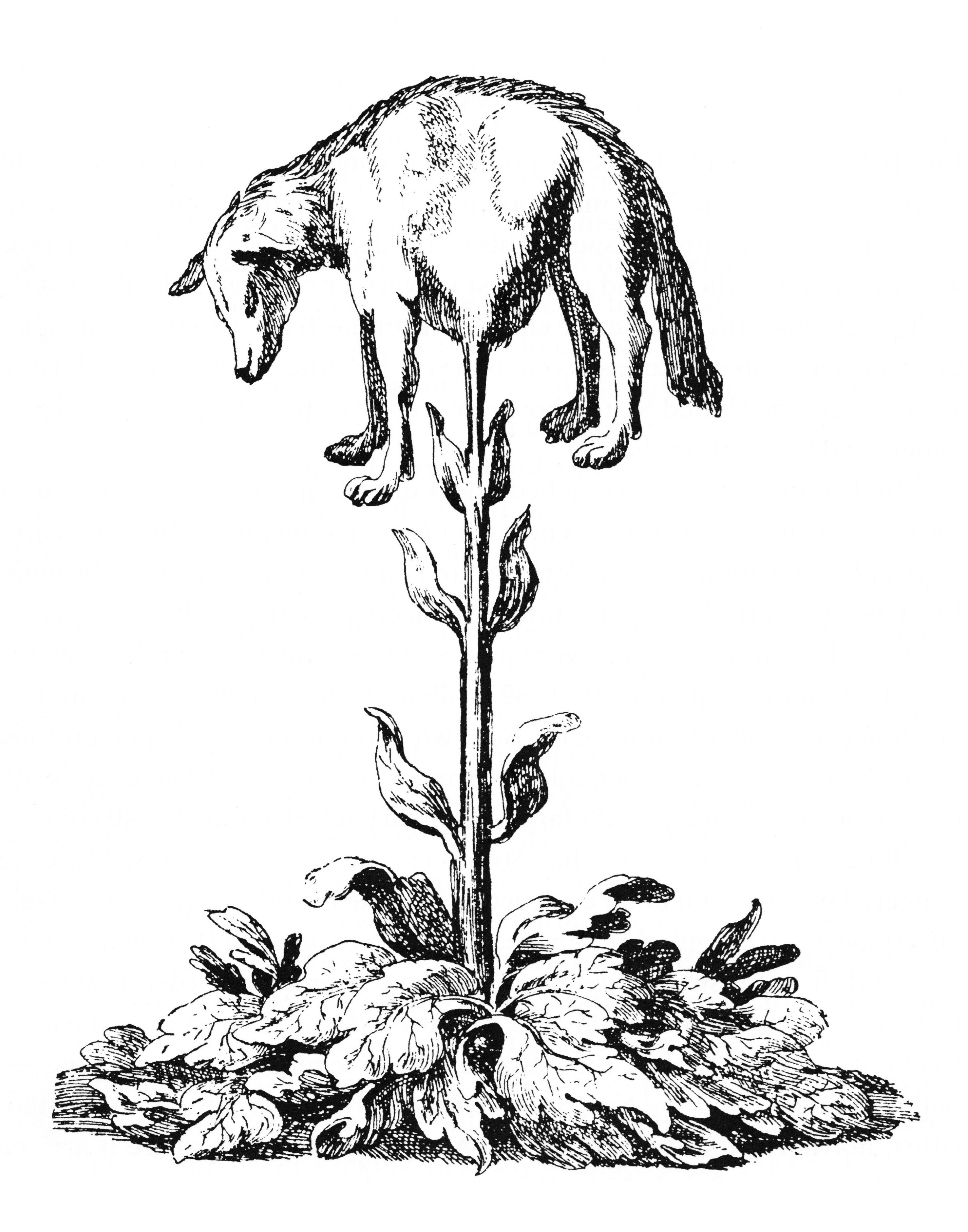

According to ancient lore, you’ve encountered the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary. Luckily there’s no need to run, as it’s solidly tethered to the ground. But though this animal-plant hybrid couldn’t go very far, the legend of it did—although completely imaginary, the vegetable lamb of Tartary crops up in ancient Hebrew texts, medieval literature, and even poetry, philosophy, and scientific musings of the Renaissance. Also called the borametz, the Scythian lamb, the lamb-tree, and the Tartarian lamb, this mythical zoophyte intrigued, inspired, and perplexed writers, philosophers, and scientists for centuries.

According to Henry Lee, a 19th-century naturalist who wrote rather extensively on the vegetable lamb, the woolly plant first appeared in literature around 436 A.D., in the Jewish text, Talmud Hierosolimitanum. According to Lee, Rabbi Jochanan included a passage detailing the plant-animal that is “in form like a lamb, and from its navel grew a stem or root by which this zoophyte … was fixed … like a gourd, to the soil below the surface of the ground.”

Later, Sir John Mandeville would refer to these creatures in his travel writings on Tartary. He refers, rather sweetly, to the lambs borne from gourd-like fruits as “little beasts,” and rather quickly follows that with, “of that fruit I have eaten.” Though we now know Mandeville wasn’t the most reliable narrator, his thoughts on the lamb-tree were taken seriously in medieval England.

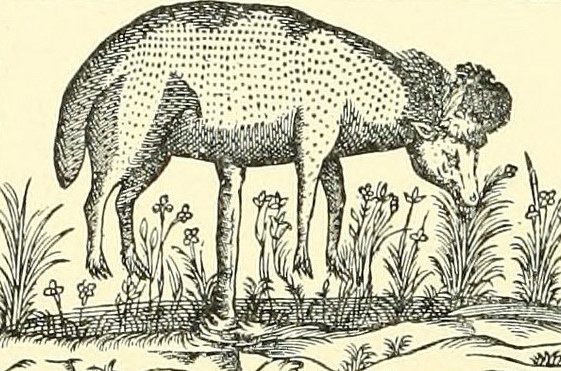

In Mandeville’s imagined anatomy of the zoophyte, the plant branched out into several seed pods from which newborn lambs would spring forth. But Mandeville’s configuration wasn’t the only one in existence. In another version, each plant bore a single fully grown lamb, with a thick coat of wool “as white as snow.” The fabled creature hovered off the ground on a highly flexible stalk, which allowed it to bend deeply enough to chomp on the grass below. There was a catch to this seemingly laid-back life: Eventually, the grass would run out. Once it had devoured all the vegetation within reach, the lamb-plant would die.

Though it may have seemed helpless, swinging around aimlessly on its stem until it starved to death, procuring a vegetable lamb for one’s own was apparently a difficult task. Most iterations claim that, because the lamb could not be extracted from the plant without severing the stem, the borametz could not be hunted, except by wolves, who somehow always get the best of the poor lamb in folklore. A human looking for a leafy lamb could track one down, too, but would have to shoot arrows or darts at the stem until fully severing it to get the woolly prize. (Writers of the time did not specify why knives could not be used.)

If one could track down a live vegetable lamb, however, it was a delicacy. Both humans and wolves alike loved the taste of lamb-plant meat, which, according to ancient writer Maase Tobia, tasted “like the flesh of fish.” And as if a lamb-vegetable that tasted like fish flesh weren’t peculiar enough, it allegedly also contained “blood as sweet as honey.”

But there was a more sinister version of the narrative. Lee includes a passage from Rabbi Simeon, who hints that the zoophyte was not a lamb-plant hybrid, but rather a human-plant hybrid. He claims that, according to the Jerusalem Talmud, the ‘Jadua,’ was a plant found in the mountains that grows “just as gourds and melons,” but in the form of a human—with a face, body, hands, and feet. Similar to the vegetable lamb, it was connected at the navel to the stem, which, if cut, would cause the Jadua’s demise. “No creature can approach within the tether of the stem, for it seizes and kills them,” he wrote. It seems that iteration was too dark for philosophers of the Dark Ages to stomach, as most devout believers of the borametz seemed to stick to the version featuring the fluffy, tasty, non-human plant.

Whether one believed the zoophyte to be lamb-like or man-like, it took until the 16th century for scientists and philosophers to begin publicly questioning the Scythian lamb. The renowned Italian polymath, Girolamo Cardano, tried to disprove it by pointing out that soil alone couldn’t provide sufficient heat for a lamb to survive embryonic development. But his argument was highly controversial. Claude Duret, an Italian linguist, botanist, and, above all, firm believer in the existence of the lamb-plant, passionately denounced Cardono. Echoing a common claim at the time, he affirmed that “in a place filled with heavy and dense air (such as is Tartary), the Borametz—true plant-animals—might exist.”

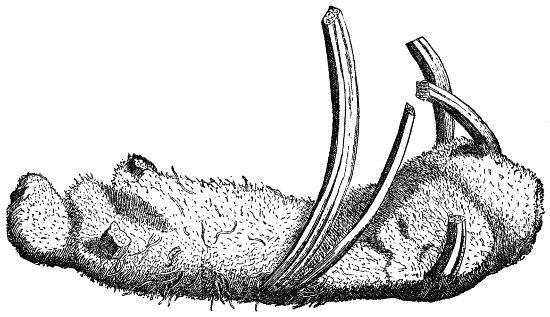

Soon enough, however, naturalists began to make the point that, maybe, there were plants that simply looked like lambs. In 1698, Sir Hans Sloane brought forth a lamb-like specimen from China, the rootstock of a fern, which was “covered with a down of dark yellowish snuff colour.” It seemed, he argued, that it had been manipulated by a clever artist to look strikingly similar to a lamb. However, there was an issue with this argument: The species that birthed these lamb-like sculptures wasn’t native to Tartary. Besides, Lee argues, the coat of the lamb-plant was depicted as “snowy-white,” while the woolly substance produced by the rootstocks was decidedly orange. There’s a better theory, Lee offers, and it looks a lot like a poorly played game of ancient Greek telephone.

Cotton was likely brought to Western Asia and Eastern Europe from India—and while the ancient Greeks didn’t really know much about the cotton plant, they felt very comfortable waxing poetic about it. Greek historian Herodotus’s writings refer to the cotton padding of a corselet sent from Egypt as “fleeces from the trees.” Alexander the Great’s admiral would later write that “there were in India trees bearing … flocks or bunches of wool.” A bit further down the line, Pliny the Elder (whom Lee calls “admirable as a writer,” but “incompetent and worthless as a naturalist”) went further off-script, erroneously claiming that “these trees bear gourds … which burst when ripe.”

And then, there’s the fact that the Greek word for “melon” can be translated into “fruit,” “apple,” or “sheep.” It’s possible that, throughout various translations of early texts describing the cotton plant among other trees, the “fruits” resembling “spring-apples” could have been misinterpreted as “spring-lambs.”

Though the vegetable lamb isn’t real, its story paints a very real picture of how science and mythology, fact and fiction, are closely connected—and often resemble one another. And while the vegetable lamb has disappeared from the minds of scientists and philosophers today, it will likely persist as a strange scientific history, an overblown origin story, and perhaps, a far-away fantasy for vegetarians with a craving for lamb.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook