The Ups and Downs of Being a Canal Lockmaster

Keeping a 170-year-old tradition alive on the mighty Muskingum.

The mighty Muskingum River winds 112 miles through southeastern Ohio, from Coshocton to Marietta, where it flows into the Ohio and, in turn, the even-mightier Mississippi. The Muskingum was, for decades, a critical route for the movement of people and goods in the region, though today it’s almost exclusively used by pleasure boaters. As the river bends around downtown Zanesville, a small city with an emerging art scene in the gentlest foothills of the Appalachians, there’s a dam, one of 10 on the river. Boaters who want to pass it need to steer toward an old but well-maintained canal on the eastern side of the river, and grab the attention of a man sitting in a small wooden shack. That’s Tim Curtis, and he’s one of the few full-time lockmasters still manning America’s waterways.

A boat that wants to get past the dam has to rise or drop 15 feet, so the canal is equipped with locks. The Muskingum’s locks are some of the last period-correct examples in the country, Curtis says, and his job has barely changed in 170 years.

Curtis’s shack sits on a narrow, verdant island, approximately 600 yards long, formed where the canal splits off the river and accessible from the town’s three-way Y-Bridge. As a boat approaches, Curtis dons a small lifejacket—“we have to wear these even if we’re mowing”—and grabs the crank handles from the shack, where they are kept under lock and key.

He attaches a crank to an old mechanism, and then uses it to manually open the first doors of the lock to let the boat in. Once the boat is in place, he shuts the door behind it and begins the process of lowering or raising the water in the lock via a valve on each door. They’re opened by crank, too, and water then flows in or out, depending on which way the boat is going. Once the lock chamber is level with the water on the other side of the lock, he opens the other set of doors and the boat can progress. His lock, #10, is unusual on the Muskingum because it is a double lock, so the process is repeated in another chamber. Approximately half a million gallons are displaced during each step. Once the boat makes it through the lock, Curtis goes back to tending the grounds until the next boat arrives.

According to Ron Petrie of the Canal Society of Ohio, there only a few hundred lockmasters employed throughout the United States, and most of them are in the industrial waterways of upstate New York. On the Muskingum, Curtis and the 11 other trained lockmasters are there to help the 7,000 fishers and boaters who use the river each year. They’re mostly taking local river trips, but it is quite possible to take a boat from Lock #10 all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico.

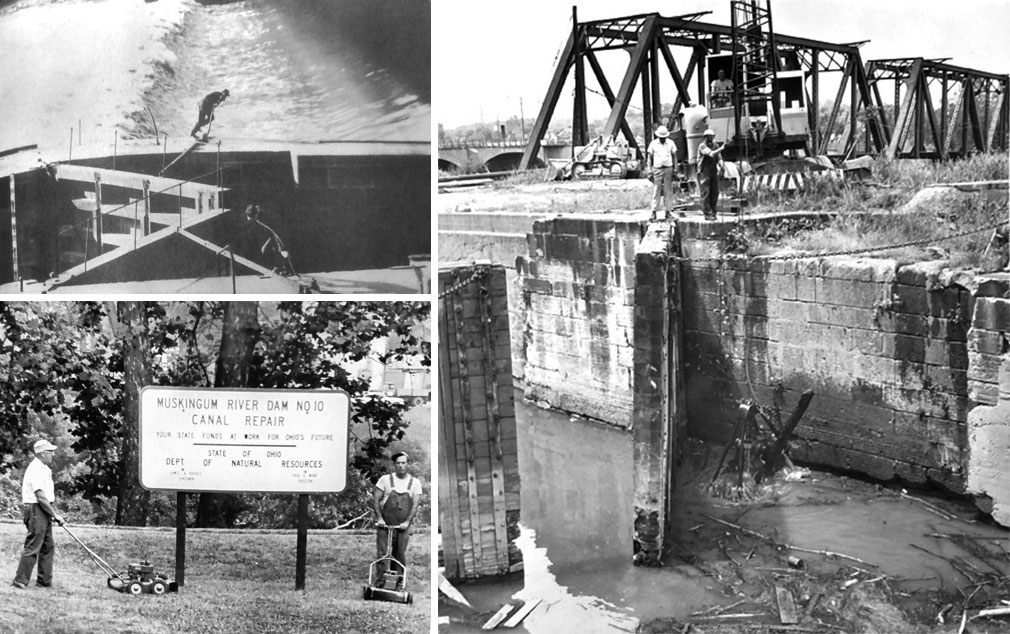

Curtis, 32, is rangy, with hair sprouting from his chin and a small moustache. He is from nearby McConnelsville, a rural upbringing reflected in his drawl and good-old-boy charm. The locks are operated by Ohio’s Department of Natural Resources as part of the state park system, and Curtis works for the parks department as a “rover,” attending to park upkeep. The longtime operator of Lock #10 moved on from the job not long ago, so Curtis has been working with it for around two years. The job requires a year of on-the-job training, he says, but most lockmasters, like himself, grew up on the river and already feel at home there.

Adjusting his camo hat, he explains that the dams and locks are what made the Muskingum navigable in the first place. The river is fairly shallow, and the dams create a “slackwater” system that deepens it, and the locks are needed to get around them. “Without the dams, it would be like a creek,” he says. “I’ve seen people walk all the way across the river.”

In fact, when European settlers arrived in the late 18th century, the shallow river meant they could only use flatboats with a miniscule draft, and most were chopped up for lumber once they reached their destinations (rather than get paddled back against the current). Plans for a lock system on the Muskingum River were hatched as early as 1812, but the Ohio General Assembly didn’t authorize construction until 1836, during an “epidemic … of internal improvement,” according to Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Muskingum County, Ohio. Twelve locks and 11 dams were installed by 1841. (One lock since has collapsed and is permanently closed.)

Lock #10’s original stone walls from 1837 are intact, and the doors are made of massive timbers held together by metal frames. The wood on the doors was replaced as recently as 1984, Curtis says, due to their creosote coating, a wood preservative that can leach out and pose environmental hazards.

At the height of the lock’s usage, people and freight moved from Zanesville to all over Ohio and beyond so frequently that the lockmaster lived in a house on the canal island, ready to allow a boat through at any hour. That house still stands, but is now used only for storage.

Operating the lock is an art, Curtis says, and requires some finesse. If you go too fast, boats can bounce around and be pulled off the cables that hold them steady. If the boat is too close to the door, it can be pulled into the whirlpool created by the valve and sucked into the door. But after years of working the river, Curtis can intuit adjustments so the water flows calmly and evenly, and boaters hardly notice what’s happening. Going through the double lock takes about half an hour. Though if you want a really quick and bumpy ride, Curtis laughs, it can be done in 20.

After a day on the Muskingum, “the boaters can get a little rowdy. In the evenings it’s not PG-rated,” Curtis says, but once they’re in the lock, they tend to respect its history and seriousness. (The danger of boating on the Muskingum is quite real. Two boaters drowned in Zanesville in June 2014 when they stole a boat and tried to go straight over the dam.) They certainly don’t want to end up in the canal water, or stay in the stuffy lock for any longer than they need to.

Once the locks and dams had been installed, the more reliable river led to an economic boom on its banks—both for the capitalists who used the system and the pool of labor necessary to staff and maintain it. Passenger boats in the 19th century were alive with card games and songs, while others carried “rather more freight and less frivolity”—upwards of 300 tons of goods at a time. Boats leaving Zanesville could go north to Cleveland, east to Pittsburgh and New York, south to New Orleans, and west to St. Paul. (Travel from Zanesville to New York took roughly two weeks.)

“For nearly 25 years … every lock frequently had a string of boats waiting to pass,” writes J. Mark Gamble in Steamboats on the Muskingum. “Each passenger boat carried 40 to 60 people. They have been called the ‘Pullman cars of the [18]50s.’” At least two babies were born en route to St. Louis in 1855, and a contingent of soldiers sailed from Zanesville to fight in the Mexican-American War, though they arrived after the fighting stopped.

The downside for Zanesville and the surrounding areas—a common predicament for towns that benefited from canals, railroads, and other means of transportation—was that business no longer had to stay in town. Local farmers were able to move their wares elsewhere for competitive prices. Land along the river became incredibly expensive, and some local people introduced ordinances against the “horrible, odious, and useless steam whistle” to their local legislatures.

Boating helped knock out the area’s stagecoach business, but river traffic was in turn diminished by the railroad, whose bridges, as Gamble put it, were built “with little regard for the needs of water carriers.” Steamboats lowered their fares to compete and bragged that while trains could only stop at stations, boats could pick up passengers anywhere along the river. But then the automobile came along, and the age of river travel and freight was largely over. Commercial traffic on the Muskingum was done by the 1920s.

Today, Ohio’s dams and locks are less pieces of necessary commercial infrastructure than tranquil historical sites, waypoints on countless summer excursions, idylls away from interstate traffic or the unending struggle of air travel. Cranks in hand, Curtis surveys his surroundings. “This is a unique place in the U.S.,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook