The Forgotten Filipino American Activist Behind the Delano Grape Strike

A children’s book about Larry Itliong aims to rectify history.

In 1965, the grape pickers in California’s Central Valley, incensed by decades of discrimination, shoddy pay, and poor working conditions, snapped. The farmers, many of them immigrants, went on strike in the city of Delano, California. The movement gained support from unions (including the United Auto Workers), activists, and church groups, and evolved from marches into a nationwide boycott of table grapes. Years of work led to the creation of United Farm Workers, an agricultural labor organization that helped farmers negotiate for benefits and better wages.

To many, the name Cesar Chavez rings familiar as a leader of this revolutionary movement. It was a huge coup for farmers, immigrants, and minority groups within the United States, and brought visibility to their struggles, particularly for Chicanos. Chavez has been honored with street names, profiles in textbooks, and a memorial that Barack Obama visited during his presidency. But what has been immortalized in history as Chavez’s victory was the effort of many people who also led that fight, and who rarely get their due. That includes Dolores Huerta, a Chicana labor leader, and scores of Filipino Americans, particularly the labor organizer and migrant farm worker Larry Itliong.

In fact, it was through Itliong’s efforts that the highly-publicized Delano Grape Strike happened at all. For years, the Filipino and Mexican migrant workers had been both kept apart and pitted against each other by the growers, who often responded to collective demands by evicting workers or disrupting life in their camps. (The great irony is that many of these farmers had taught the growers about harvesting grapes in the first place.) In the early 1960s, each of these groups had been mobilizing on their own. But one day in September 1965, farmers gathered in the Filipino Community Hall and voted to go on strike against the growers. Itliong eventually approached Chavez, and asked him to join forces for the strike. Itliong also co-founded the United Farm Workers the following year, and helped lead the organization as an Assistant Director. So it’s strange that he’s not mentioned in the same breath as Chavez.

Itliong’s own story has hid in plain sight from many Filipino Americans, too. “The crazy thing is that we had to go away to college to find out about Larry Itliong,” says Gayle Romasanta, a writer and publisher who grew up in Stockton, where Itliong resided. Romasanta, who is a descendant of agricultural workers, was dismayed when her eldest child came home one day with a list of potential historical figures to write a report about. “And there was nobody for her to really identify with, or people of color period,” she says. In searching for an alternative, she thought of Itliong, but came up short on information. “I was really surprised there’s no book written about him,” she says. “There’s actually no nonfiction children’s* book about Filipino American history, which blew my mind. And we’re the oldest Asian-American group in the United States—we’ve been here the longest.”

Romasanta, who had written the children’s book Beautiful Eyes, called up Dawn Mabalon, a historian, San Francisco State University professor, and old friend, who happened to be working on a biography of Itliong. “So I approached her and said, ‘Hey, listen: We’ve got to write [a] children’s book.” For Mabalon, her proposal was serendipitous. “I was really frustrated because I couldn’t find the time, the resources, to finish my scholarly biography [of Itliong],” she says. “Meanwhile, we were cognizant of how absent Filipino American history was in K-12 schools.”

In her 2013 book Little Manila Is in the Heart, Mabalon wrote about the Filipino story on the United States’ West Coast, particularly about the “struggle to make communities, build families amidst just virulent racism and violence, laws that barred them from citizenship and marrying white women,” she says. It was only through this research that she began to learn much more about Larry Itliong’s story. Like Romasanta, Mabalon—who also hails from Stockton, and comes from an agricultural background—didn’t know that Filipinos had kick-started the grape strike until she left for college.

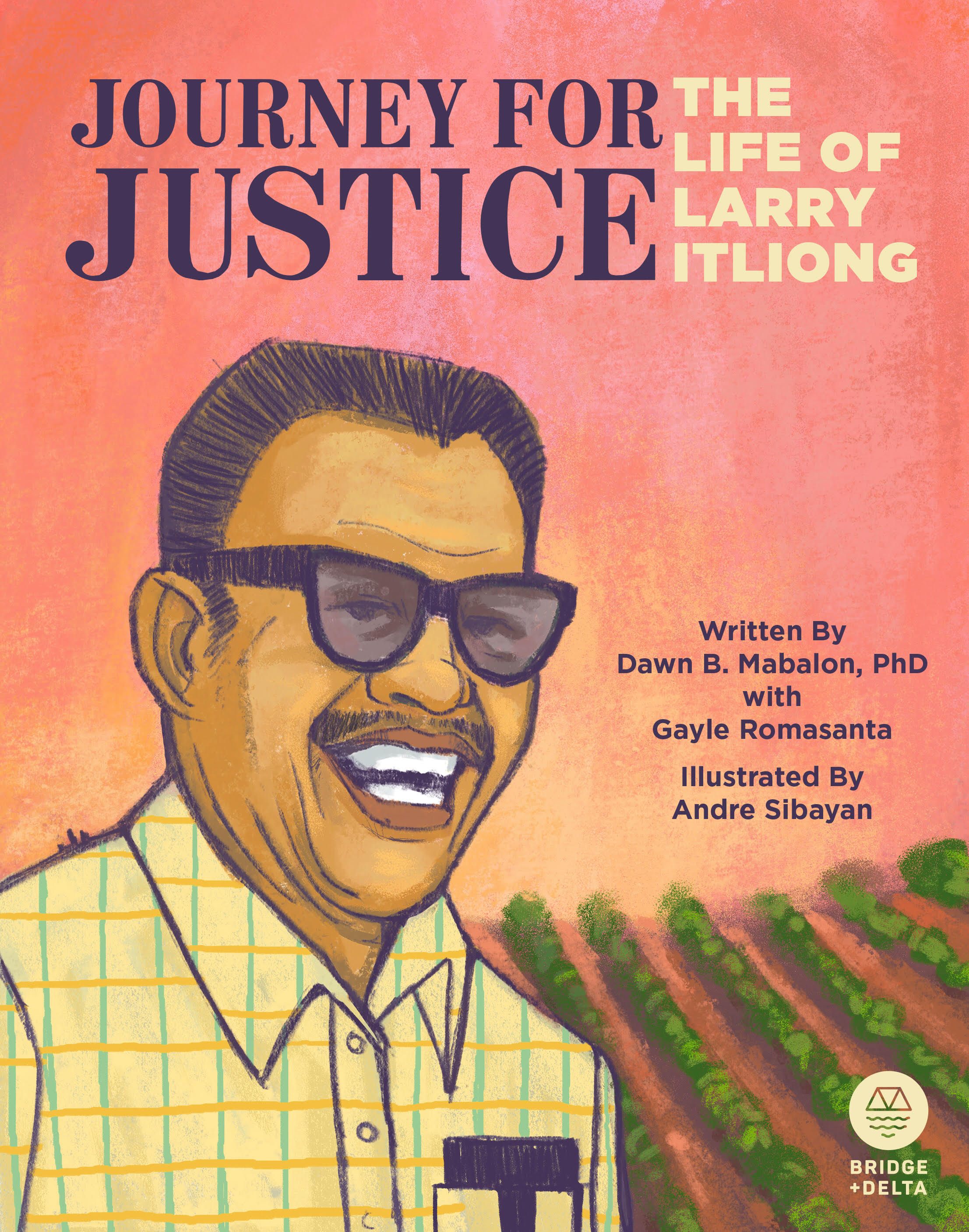

That’s how the pair’s book, Journey For Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong (due out via Romasanta’s publishing house Bridge + Delta in October), came to be. The story of Larry Itliong will be the first of eight children’s books, with each focusing on a pivotal figure from Filipino American history. They started with Itliong because, as Mabalon puts it: “Of all historical figures, he makes the most impact on a national scale, yet he is the most invisible and the most ignored.” The book’s publication also comes at the heels of recent legislation passed by California in 2013, which now requires the state’s curriculum to include the contributions of Filipino Americans in the farm labor movement. The late labor leader’s birthday, October 25th, is now recognized as Larry Itliong Day in California.

One reason for Itliong’s low historical profile has to do with how social movements have historically been covered in the media. Romasanta recalls a story about a writer, who decided not to include any of Larry Itliong’s interviews in a piece about the UFW, and perhaps spurred a trend of reporters only speaking to Chavez. “I think that Cesar had a very charismatic personality … [During] the Civil Rights movement, so many other people played big roles, but the media only wanted to talk to Martin Luther King,” Mabalon adds. “So I feel like it’s not just [Itliong]. Historians have spent the last few decades trying to recover the stories of so many unsung people in all of these freedom movements.”

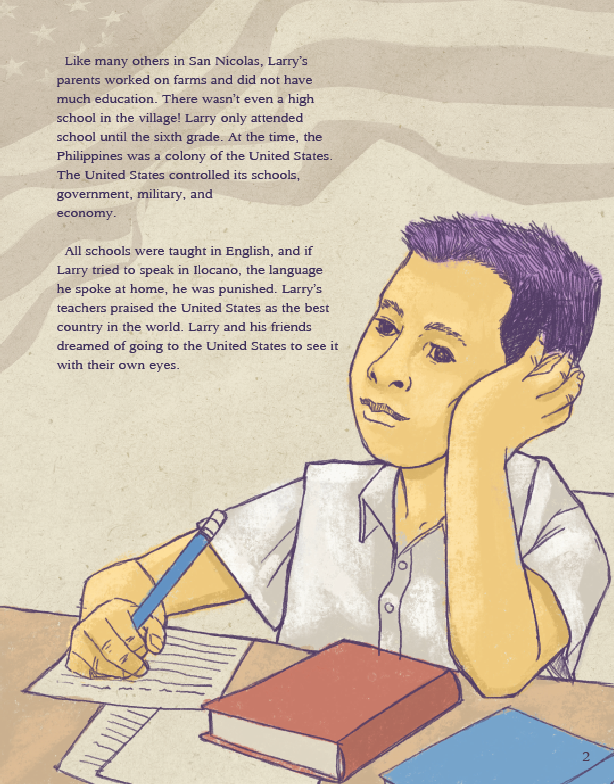

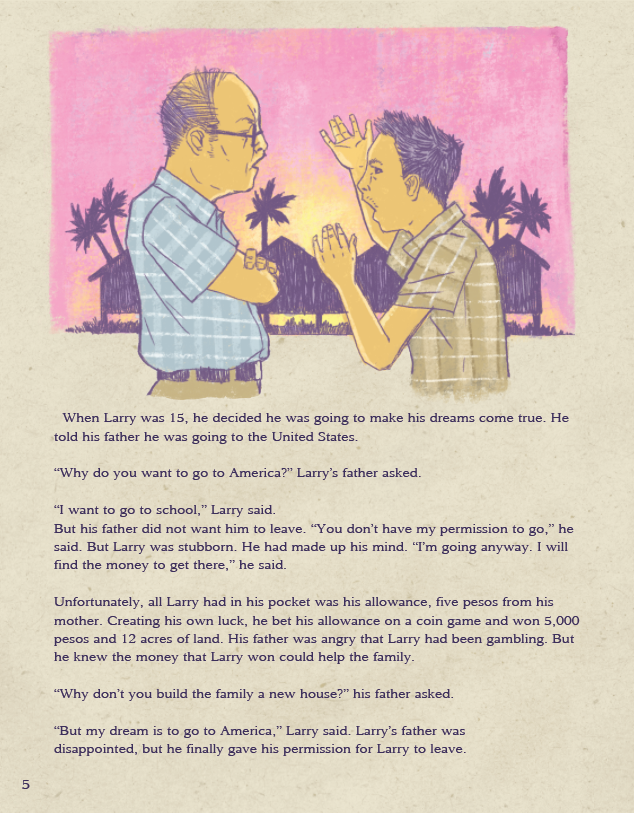

Romasanta and Mabalon felt it was crucial for Americans to learn about these efforts earlier, hence the decision to write a children’s book. The book addresses Itliong’s youth in the Philippines, which was then a colony of the United States, and the staggering racism he encountered upon his arrival in America in 1929. It weaves through Itliong’s labor in the fields, his contributions to the movement, and the strike itself. “I hope that for young people, it becomes: How do we build coalitions and solidarity?” Mabalon says.

The Bay Area-based illustrator who created the visual part of the book, Andre Sibayan, was inspired by the prospect of a Filipino American history book that kids could identify with. “I wanted kids to see themselves in the imagery. Not just, ‘Hey, it’s just this group of people that struggled. There are people who look like me, my mom, my dad, my uncle.’”

But untangling a gnarled history came with its own set of challenges. One of those included depictions of Itliong himself. A complex figure known as “Seven Fingers” (because he mysteriously lost the other three), Itliong was a known gambler and a prolific cigar-smoker. Another obstacle was describing the movement in a way appealing to children. So they turned to their community. “We had so many people read it: elementary school librarians, college librarians, we had experts in farm labor history, former UFW organizers, Larry Itliong’s son, Johnny, and his son all read the book,” Mabalon says. They also had kids ages 9 to 12 read the book and offer feedback. “People have been so excited, parents as well as kids,” she says. “There’s just so much hunger for an inclusive history.”

The two authors stress that the intention isn’t to detract from the efforts of Mexican migrant workers, Cesar Chavez, or Dolores Huerta: It’s about sharing the spotlight, and recognizing the shared efforts behind large-scale change. “At the end, we wanted it to be uplifting and to show that Filipinos and Mexican Americans were able to work together, demand their rights as farmworkers, and get their dignity back,” Romasanta says. Mabalon adds: “That’s a lot more useful, accurate, and powerful story, and has so much more utility for our lives today.”

*Correction 5/25: This article previously stated that no nonfiction books about Filipino American history are available. Until recently, there has been no nonfiction children’s book about Filipino American history.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook