Need a New Hobby? Go Looking for Hidden Letterboxes

Letterboxing, as it’s known, is a centuries-old scavenger hunt.

Across the world, a network of hobbyists is exchanging clues and secretly hunting down caches they use to communicate with each other, all while closely guarding their search from the “muggles” around them.

They share the clues through exclusive catalogs, on certain corners of the internet, at hiking trails and libraries, or by old-fashioned world of mouth.

Sometimes the directions are straightforward:

From the third stone wall corner that comes to a point right near the dirt road - just before the dead red pine grove and just after a patch of slickrock - take about 8 steps west, then carefully pry open the lower lip of the pink granite mouth

Sometimes they take a little more thought:

Walk east on Ventura 3 minutes. If you like, stop to get a mermaid high. Continue east. Stop at Book of Stars. Muggle alley. Stairway to heaven. Quick right facing north.

Sometimes they don’t even tell you exactly where to start:

Find the tower whose 161 steps will bring you to a fantastic view of Cayuga Lake. This tower also houses a very unique instrument.

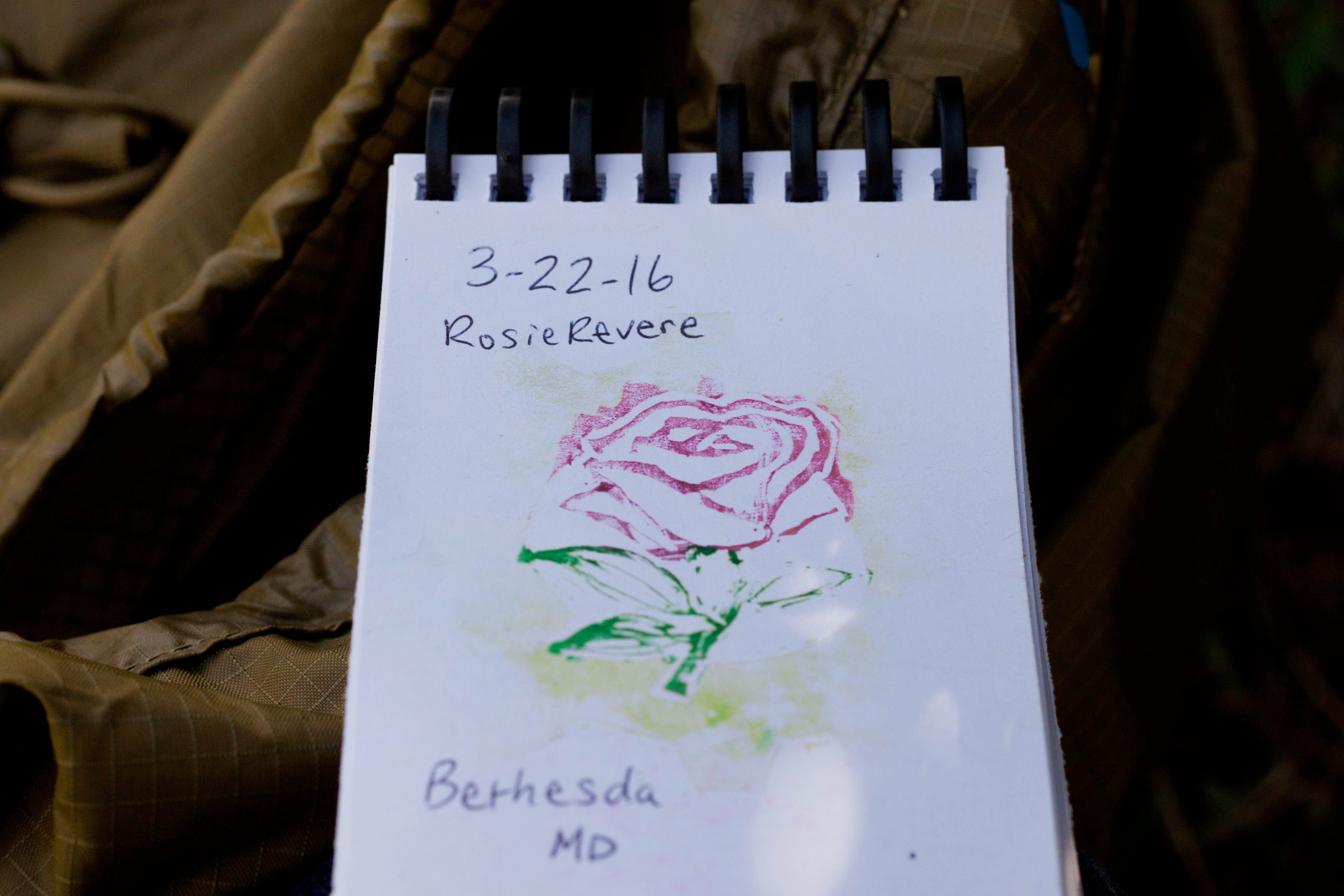

But all clues lead searchers to to a hidden object called a “letterbox,” where they will find a small notebook and a rubber stamp, usually one that’s been hand-carved by a fellow letterboxing enthusiast. Letterbox visitors sign the notebook with their chosen alias and leave a signature stamp of their own in the book. Then they’ll use the stamp they found to memorialize the search in their own notebook.

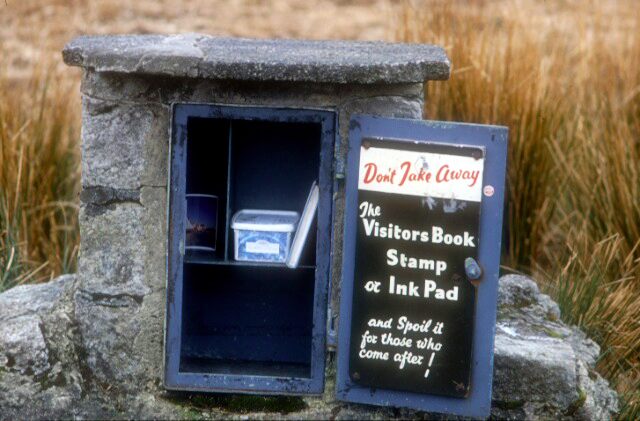

Letterboxing began in the mid-19th century, when a man knelt in the peat bogs of Dartmoor, England, constructed a small cairn, and placed a glass jar inside. He told other hikers to leave something in the jar if they came across it, and people began to leave messages for future visitors.

With that act, James Perrott unwittingly laid the foundation for a hobby that continues more than 150 years later.

Perrott was one of England’s first moorland guides, offering local expertise to a wave of middle-class tourists eager to explore the wild countryside. Perhaps it was this occupation that led him to build what later became known as a “letterbox” at a landmark in northern Dartmoor known as Cranmere Pool.

Amid the vast, deserted moors, Perrott’s structure served as a place for passers-by to leave their calling cards, which were collected by future visitors to the lonely spot. Legend has it that Charles Dickens, who once hired Perrott as a guide, was one of the early visitors.

People eventually began leaving similar structures in other parts of the moor. Perrott’s 1854 cairn was followed by caches placed in 1894, 1938, 1951, and 1962, which are still deep within the moorland and challenging to locate, according to the website Letter Boxing on Dartmoor.

But the Victorian-era hobby spread beyond the moors and even the British Isles. Modern letterboxes can be found in the woods, in the desert, in cemeteries and cities, in bookstores and libraries, in dog parks and theme parks and museums. They have been placed in the remotest parts of the globe, like Barrow, Alaska, and in the bustling streets of major cities like New York and Los Angeles.

Although letterboxing remains an obscure hobby, many people are familiar with its cousin: geocaching. The GPS-focused activity became popular around 2000 and appeals to the same primal, treasure-hunting instinct that seems to be part of the human psyche. Participants use a GPS device to navigate to a hidden cache and remove a small trinket left in the box, replacing it with something new.

But, to some letterboxers, geocaching can seem superficial. When you’re just plugging coordinates into a GPS device, where is the hunt? When you’re finding and hiding cheap toys, where is the treasure?

“Geocaching never really appealed to me,” says Ryan Carpenter, a 42-year-old software engineer from Seattle who is so into letterboxing that he founded one of the premiere letterboxing websites in the United States, Atlas Quest. “What would I do with a plastic spider ring or some other Happy Meal toy? The idea of discovering miniature works of art in the woods appealed to me a lot more.”

The original practice of leaving calling cards in remote boxes has evolved into sharing unique, hand-carved rubber stamps. Each letterbox contains a stamp, usually carved with an image related to the place where it’s hidden, and hobbyists collect these stamped images as records of their “finds.” Each person also has a signature stamp, ideally hand-carved, which they stamp in the box’s logbook and sign with their “trail name.” The result is something that feels far more special and personal than swapping mass-produced pieces of plastic.

But letterboxes really make you work for that stamp. After finding clues online, left in a public place, or spread by word of mouth, hunters must solve the riddles and use landmarks, maps, compasses, and, most of all, perseverance.

“I didn’t find the first one I looked for—very frustrating!” says Carpenter (trail name: Green Tortuga), recalling how he raced into the woods after noticing a few sentences about the hobby in an outdoors magazine. “The clues didn’t seem to make any sense at all. What it described was nothing like what I was actually seeing.”

After some initial frustration he searched for—and found—a second letterbox, but the failure of his first hunt stuck with him.

“I was lying around a couple of weeks later thinking about it,” Carpenter says. “Click. I suddenly realized that I had been looking in the wrong location. Probably. I needed to go back and search again.”

He did. And he found the box.

For Wanda Miner, the journey to letterboxing obsession began with a fractured spine.

Miner, a Rhode Islander who is now in her 60s, worked in military intelligence until she was injured in a serious car accident.

“I later used long-distance backpacking as a route to recovery,” she wrote in an email, “hiking five times between Georgia and Maine on the Appalachian Trail, four times between Mexico and Canada on the Pacific Crest and Continental Divide Trails, and doing multiple backpacks of many other trails as well.”

In July 1999, Miner found herself back in the place that inspired her lifelong passion for hiking: New Hampshire’s Mount Moosilauke, which she climbed as a teenager. There she stumbled upon a clue sheet for something called the Moosilauke Historical Quest outside a Dartmouth College-owned lodge there.

The quest, of course, led to a letterbox.

“I was delighted to follow the clues to learn about the history of the lodge and its skiing heritage,” says Miner, “but for some reason the box was jammed so tightly into its ‘hidey-hole’ that I couldn’t extricate it.”

That was okay by Wanda, though. Even today, after she and her husband Pete have logged upwards of 50,000 letterbox finds across all 50 United States, and more than 700 “plants” of their own, the stamp art just doesn’t hold much allure for her.

“I had no real need to sign in or get the stamp or anything like that,” she says. “Just following the clues, learning something and finding the box location was enough reward for me, and that has stayed with me as my basic motivation for letterboxing right up to the present day!”

Miner counts the two boxes she found the next day in Vermont as her first official finds, but she eventually re-visited the Mount Moosilauke box and enlisted some members of the lodge’s kitchen crew to pry it out with a crowbar.

Websites like Atlas Quest and Letterboxing North America (LbNA) have made the hobby more accessible to a new generation of hunters in North America. Sometimes, though, modernity chips away at the romance of the pastime.

“Pete especially dislikes ‘drive-bys’ near dumpsters or guard-rails, and cemeteries or gatherings with way too many boxes all crammed into one area,” says Miner, “because that seems to him to defeat the purpose of letterboxing, which he feels is to get out to explore as many different places as possible, not just to collect as many stamps as possible!”

Places the couple has discovered through letterboxing include “a secret ‘weeping spring’ in the middle of the desert in Arizona, a hidden natural bridge in Arkansas, a remote slot canyon in California, a sinkhole in Florida, a ‘sea geyser’ in Mexico (and) some magical ringing rocks in the mountains of Montana.”

Dumpster drive-bys aside, there are still plenty of options for boxers like Wanda and Pete, who say they “enjoy a really well-placed series in a lovely preserve, like so many that have been coming out lately.”

And for the truly old-school, there are still boxes spread across the rugged English moorland, many with clues only available by word of mouth.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook