What It’s Like to Build and Operate a Tiny Traveling Bookshop

A French theater director crowdsourced his dream.

Jean-Jacques Megel-Nuber didn’t always imagine he’d be living in his bookshop, but he knew he wanted it to move.

At first, he pictured an itinerant bookstore on a boat. Or in a chalet—appropriate, given his Alsatian roots—but one that was towed behind a tractor trailer. “I didn’t want to wait for people to come to me,” he says. “I wanted to go to them.”

Until four years ago, Megel-Nuber worked as the director of a traveling theater troupe for children, bringing culture and live performance to parts of France that weren’t necessarily equipped for such shows. It inspired him to continue an itinerant lifestyle, but one that carried a mission or project to share with the people he encountered.

Actually making his roving bookstore real, however, required much more effort than he expected. Megel-Nuber—an imposing-looking man with a gentle, natural ease with people—spent six months just trying to conceive of its form and shape.

“Since I was going to be spending a lot of time there, it had to be a space where I felt good, so I couldn’t imagine anything other than wood,” he says. “And it’s logical: After all, books are made of paper.”

Easier said than done. It wasn’t until he connected with Pauline Fagué and Romain Saunier, founders of La Maison Qui Chemine (“The House That Plods”), a company that specializes in mobile tiny houses, that his dream truly took form, with funds raised from international crowdsourcing site Ulule.

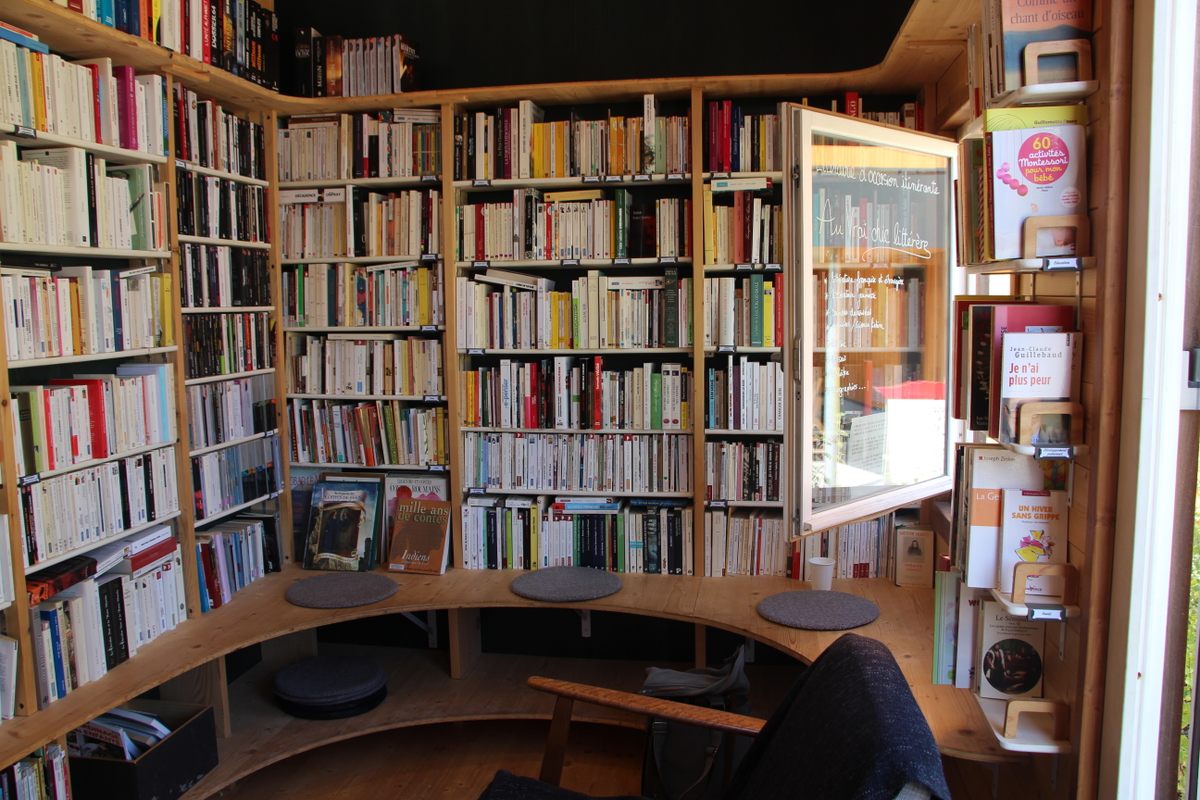

Fagué, who designed the project in 2016, says that she took her inspiration from the image of “romantic” libraries. “I thought about Hogwarts, about bookshops with buckling shelves from the weight of old collections, like in Lyon, where I studied,” she says. “These places are true bubbles where you completely change dimensions, surrounded by a cocoon of life that invades you, somehow: the smell of paper, the shape of the bindings promising so many different adventures. I wanted to re-create that in the bookshop. I remember working all night, from the moment Jean-Jacques got in touch, to the next day, when we met for the first time, to show him the first 3-D mockup of his project.”

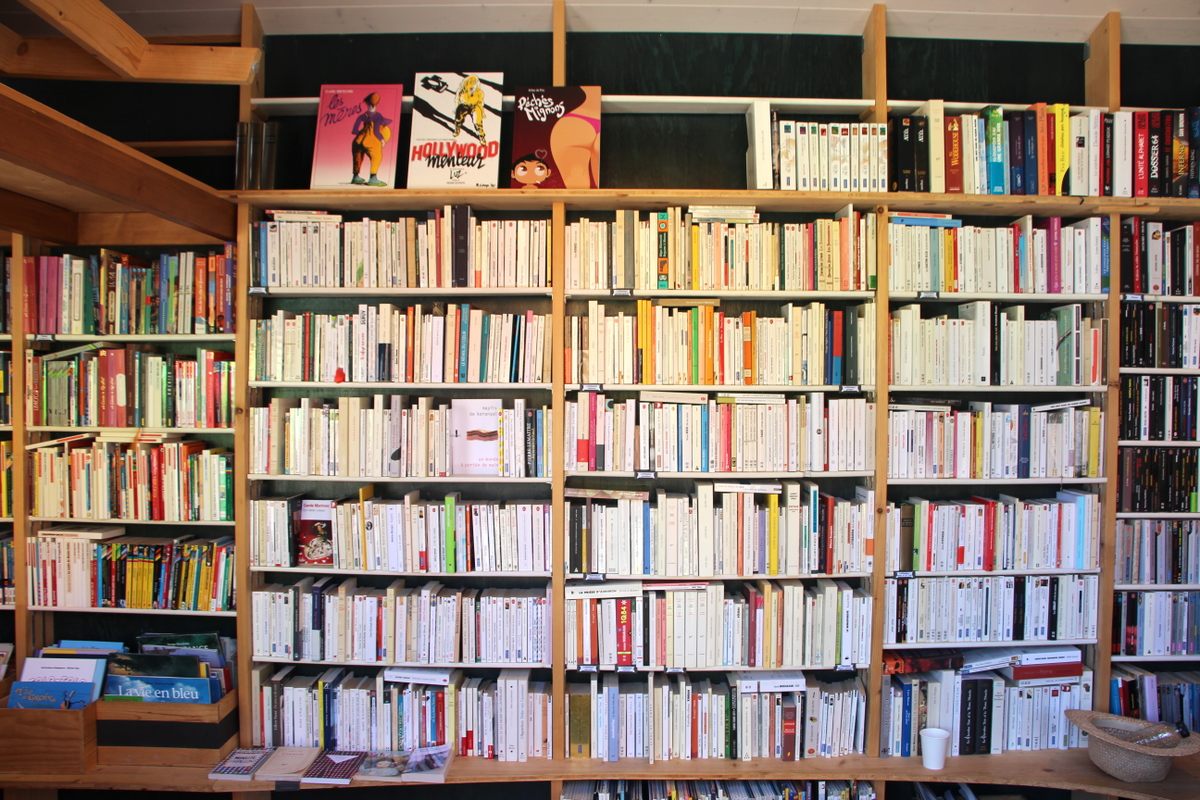

The final version is simple, but distinctive and unique: The bookshop is 120 square feet inside and is made almost entirely of pine sourced from the Vosges woods near Fagué and Saunier’s former workshop. Porthole windows bring light into the cozy space, which is divided into a reading nook on the right and register area on the left. Beyond the checkout is a toilet and a cooking corner, and above it all is a mezzanine: Megel-Nuber’s bed whenever he’s on the road. Everything else, as one might expect, is covered in books.

The bookshop is as light and as eco-conscious as possible. To insulate the structure, the team used recycled cotton from Emmaüs, a collective of charity shops founded in 1949 with 115 locations all over France. In lieu of traditional paint, they used a flour-based coating (which also helps with Megel-Nuber’s allergies).

Megel-Nuber stopped by about every 10 days during construction, and lent a hand whenever he could. “I couldn’t do much, because of the insurance, but I sanded, I painted, things like that,” he says. “So bit by bit, I took ownership of it.”

Completing the shop itself was a big step—but there were more to come. Once the trailer was finished, Megel-Nuber needed to fill it. He curated a selection of 5,000 different books of all shapes and sizes to fill its shelves. And that presented some issues. Though the structure could take it, towing 3.5 tons (both trailer and books) is not covered by a regular European driver’s license, so Megel-Nuber needed to train and test for a new one, called a BE license, that allows a driver to pull a trailer of that size.

“It took me 15 months to get it,” he recalls, noting that the test had recently grown harder—and he’s not usually one for tests. “It was horrible.”

In July 2017, new license finally in hand, Megel-Nuber was ready for the open road, and the assortment of festivals that were familiar to him from his theater days. Organizers were eagerly awaiting the project. “People had been waiting for a while,” he says. “And so I called and said, ‘It’s all good! I can come!’ And it really started from there.”

Today Megel-Nuber tows the shop behind a light commercial Iveco van from town to town throughout his native Alsace and nearby Jura. He attends about 10 festivals of various kinds a year, and he also occasionally parks the shop on village squares—perhaps when someone in the mayor’s office has a taste for literature.

Of course, driving an entire bookshop has its challenges. How, for instance, to keep the books on the shelves?

“I asked each one to stay in place while I was driving,” he deadpanned, before showing off the system of panels, secured by elastic, that do the job. Once he arrives, set up is quick—a staircase, some mats—and he tends to stay in one place only a few days before pulling up the stairs, securing the books, and heading home.

Altogether Megel-Nuber spends about four months a year on the road. During that time, he lives in the bookshop itself. The only thing the space doesn’t have is a shower, though he says it’s easy enough to find one at a gym or even the local fire station.

For the remaining eight months of the year, Megel-Nuber works to restock his shelves. In fact, before meeting the writer in the Alsatian village of Mutterholtz, he texted to say he’d be late; he had to drive to nearby Sélestat, where a rarely open Emmaüs was welcoming him to go through their piles of secondhand books—the only kind he sells. “That’s part of my job,” he says. “Sorting through books people didn’t want to keep, but that are still good. That other people might like.”

Most of his initial stock he found in about 30 Emmaüs shops throughout France. “And people would give me books,” he says. “They’d say, ‘Oh, I want to get rid of my whole library and start again.’ And they’d give me a thousand books all at once. It was crazy.”

He recalls one 97-year-old woman, who had helped with his crowdfunding campaign but who passed away before the shop was ready. She bequeathed her entire library to Megel-Nuber.

While he currently has about 12,000 books in stock, only 3,000 made the trip to the Avide Jardin Festival in Mutterholtz, where a series of musical performances and a beer garden enlivened one of the last summer days in Alsace. The books that didn’t make the journey live in the hallway outside his small apartment in nearby Mulhouse—an arrangement that may or may not have to change.

“Last week, someone moved in [next door],” he says, chuckling nervously. “We’ll see … maybe I can claim seniority or something.”

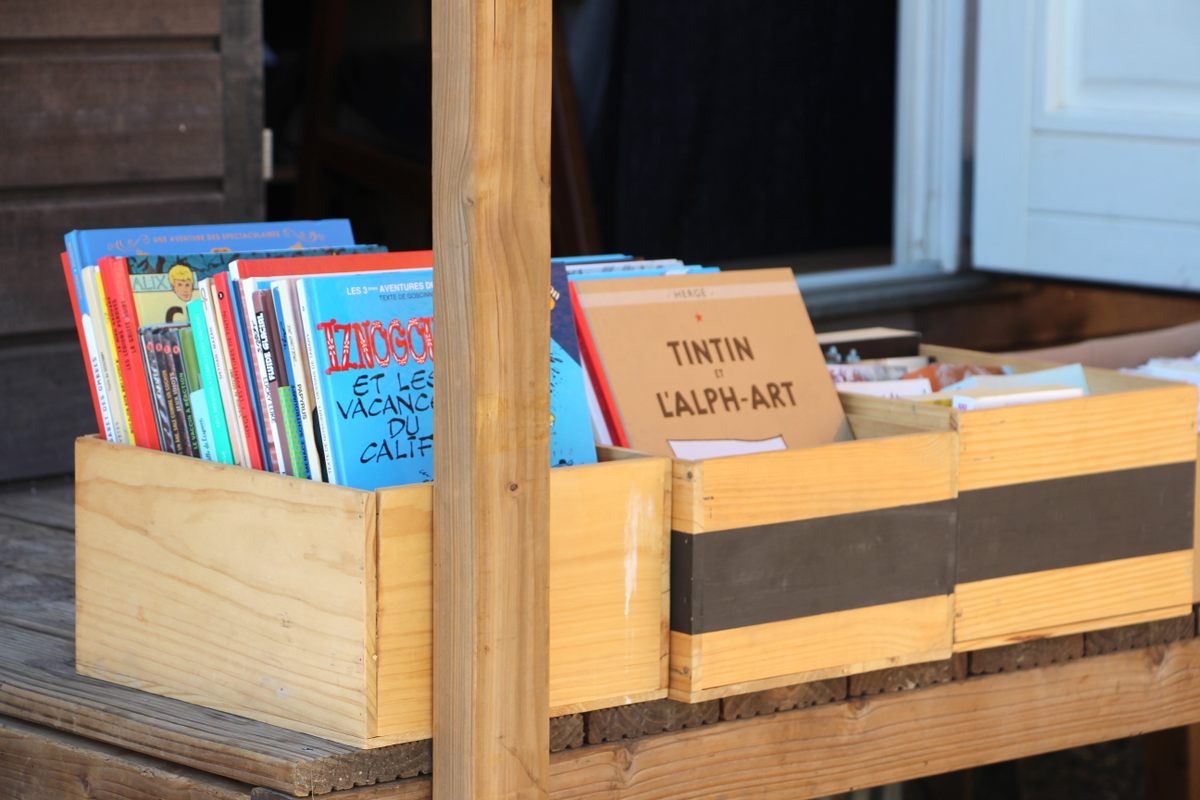

This event, centered around street music and storytelling, inspired him to bring his entire collection of fables and folktales. (He also has enough children’s books to turn the entire shop over to them if he wants.)

“I often have a preference for children’s literature,” he says. “But good children’s literature. There’s tons of crap out there, McDonald’s books.

“Sometimes, I turn into an accidental day care,” he goes on. “Parents hanging out, having a drink, and since the kids are on their own, they come in and read comic books.”

As the first concerts of the festival began, visitors wandered up the wooden steps and into the small space, browsing, but often showing more interest in the shop than the books. Megel-Nuber, for as shy as he seems at first, was a genial host, especially when asked for recommendations.

“I’m reading a book right now—I’m only about 30 pages in—but I can tell I’m going to like it,” he says. It’s set in ancient Greece, he explains—one of his passions from his studies in archaeology. He then launches into an in-depth conversation with another client about a German ballet dancer, only to be politely interrupted by a small child asking about the newest book in a middle-grade series.

And yet, despite his eclectic and wide-ranging interests, and the constant presence of so much reading material, Megel-Nuber claims he doesn’t read enough.

“I never feel like I do,” he says. “This month, I read a lot. About 15 books. And in a year … maybe 120? 130?”

“No,” he says, without even a hint of irony. “I don’t read much at all.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook