The Little-Known History of Seafaring Pets

From war to exploration to pleasure cruising, pets have often accompanied us on the oceans.

It gets hard to tell when you go back that far, but humans—Homo erectus in this case—probably crafted the first seaworthy vessel some 800,000 years ago. Since then, our ability to build boats and take to the seas has been critical to many of the most important human processes, from migration and commerce to exploration and, of course, war. But we did not become a seafaring species alone. Alongside brave seafaring men—and women, when they were allowed on board—there were often equally courageous pets.

When researchers conducted the first global study of ancient cat DNA they found that our feline friends were domesticated in the Near East and Egypt some 15,000 years ago, and later spread to Europe thanks in part to mariners, from the Phoenicians to the Vikings, who often took them on board to ward off rodents (another frequent human companion at sea, though not by design). A few thousand years later, the Romans took chickens on board military ships to predict the outcomes of battles—if the hens ate, victory could be expected. Roman general Publius Claudius Pulcher tried this trick before the Battle of Drepana against the Carthaginians in 249 B.C. He ignored the bad omen and threw the birds overboard. The Roman fleet was nearly wiped out. Despite this anecdote, the roles played by our maritime animal companions rarely make the history books. It is only recently that cultural institutions around the world have begun to pay attention to the history of animals at sea.

“For some reason a few years ago many maritime museums from the United Kingdom to Australia and the United States were hosting exhibitions about pets at sea, so I decided to start gathering information on this,” says Patricia Sullivan, founder and curator of the online Museum of Maritime Pets. “At first I thought this was going to be my retirement project, but almost overnight people started finding us and sending us photos, journal entries, or other written accounts on maritime pets.”

Sullivan founded the resource in 2006, and runs it with four volunteers from her home in Annapolis, Maryland. She defines a “maritime pet” pretty broadly: “We include animals living or working on or near the water, who collaborate with man in times of peace and war.”

Dogs, cats, and prescient chickens are included, but so are cormorants, which have been domesticated as fishing birds in parts of Asia, as well as much larger animals such as the bears and reindeer that played important roles in northern maritime history.

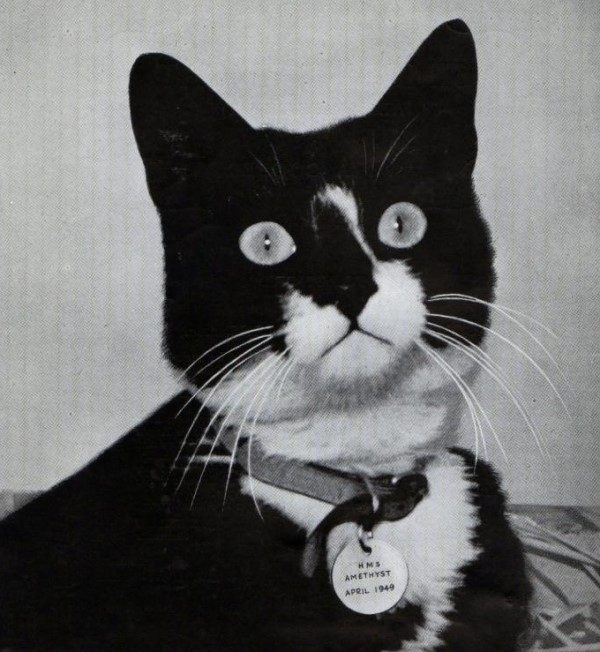

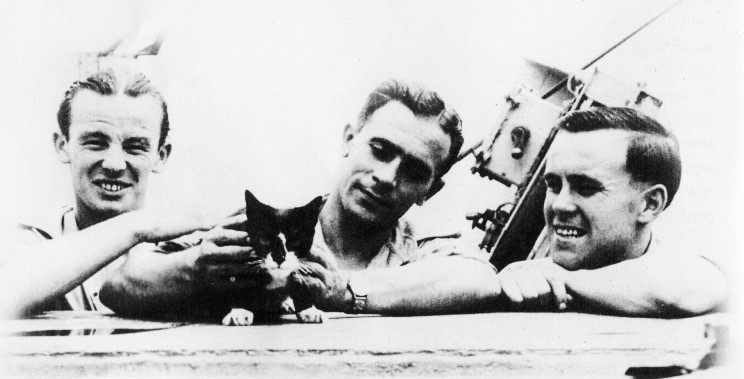

One maritime activity in which pets have shined is war. Sullivan shares the story of Simon, a cat serving on the British Royal Navy sloop HMS Amethyst, which was trapped on the the Yangtze River for three months after being attacked by the People’s Liberation Army during the Chinese Civil War in 1949. The brave cat was awarded the prestigious Dickin Medal by the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, a British veterinary charity, for surviving injuries, killing off a rat infestation, and raising the crew’s morale. “The English army awarded many medals to dogs but it was the first cat,” Sullivan says.

“One of the most famous stories here in the U.S. is that of Sinbad, a Coast Guard mascot that served in World War II,” Sullivan adds. Sinbad was a mixed-breed dog that served aboard USCG Campbell, a 327-foot vessel that defended American convoys during World War II. Following a 1943 U-boat attack that almost sank Campbell, Sinbad became a media sensation. According to Eddie Lloyd, editor of Coast Guard magazine, he was the canine incarnation of a true sailor. “Sinbad was a salty sailor, but he’s not a good sailor. He’ll never rate gold hash marks nor good conduct medals,” Lloyd wrote. Sometimes the dog ran amok in ports or caused trouble in foreign countries. “Perhaps that’s why Coast Guardsmen love Sinbad—He’s as bad as the worst and as good as the best of us.”

During his seven years aboard Campbell, Sinbad was as awarded six medals, including the American Defense Service Medal and the World War II Victory Medal. After his death, a granite monument was erected in his honor at Barnegat Light, New Jersey.

Pets were also trusted companions for maritime explorers. “Many pets were working animals on exploration vessels,” Sullivan says, with dogs used for hunting at ports of call and cats on exterminator duty. More than all of this, seafaring animals played important emotional roles on long, grueling, monotonous, dangerous voyages plagued by uncertainty. “Sailors were out at sea for months or years at time, so pets were important de-stressors” she says. “I think people would have gone mad without something to pet.”

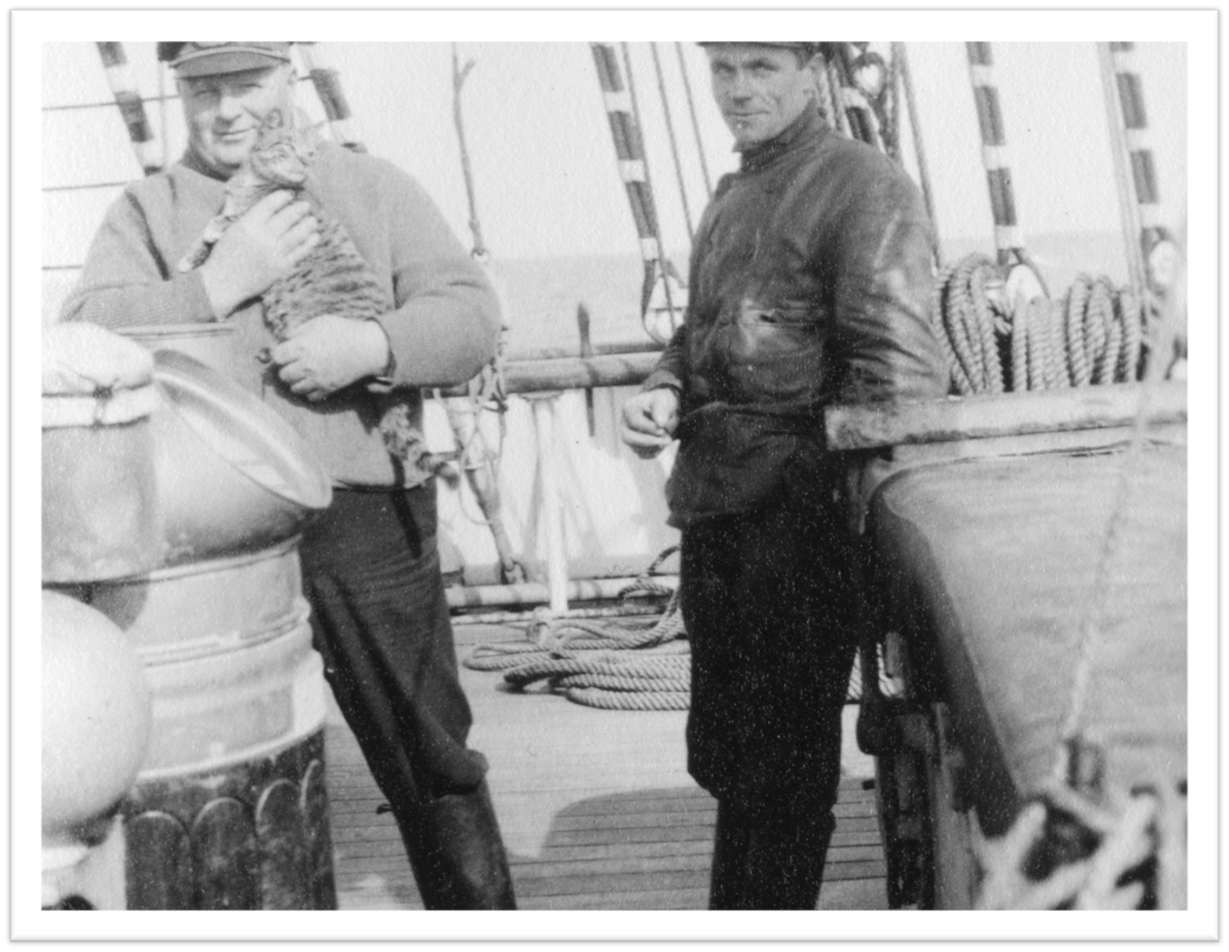

A few years ago, Sari Mäenpää, a curator at the Forum Marinum Maritime Centre* in Turku, Finland, was working as a researcher at the Maritime Museum of Finland when she first really noticed the presence of pets in the museum’s image archives. “I came across loads of photos, especially from the sailing ship era, where cats and dogs were portrayed in ‘official’ crew photos, and suddenly I started seeing images of them everywhere.”

This proud visibility presents a puzzle: If pets were so important to crews, why is their presence so poorly documented? Mäenpää wonders if the culture of the sea doesn’t play a role. “The topic of animals at sea has not really been looked at or analysed critically before,” she says. “I would say that historians were reluctant to reveal aspects of maritime life that expose cracks in hegemonic masculinity.” So Mäenpää decided to investigate further and produced an article, “Sailors and Their Pets: Men and Their Companion Animals Aboard Early Twentieth-Century Finnish Sailing Ships,” recently published in the International Journal of Maritime History.

Mäenpää explains in the article that, in the very hierarchical social environment of a ship at sea, displays of emotion were considered weak or feminine. Animals were the only tolerated objects of affection. “Sailors were not defensive or secretive about their need for pets,” she writes. “Pet owning was not in conflict with the rugged masculine self-image of sailors.”

Mäenpää offers the example of Kirri, a cat aboard Parma, a Finnish sailing vessel whose 1932 journey was documented by its co-owner, Alan John Villiers, an Australian who left behind many journals about his sailing adventures. Kirri was a “lovely little Persian kitten” that someone donated to Parma’s captain in Port Broughton, Australia. As chronicled by Villiers, Kirri quickly climbed up the social ladder of the ship’s menagerie—two rabbits, a few pigs, a dog, and another feline owned by young apprentice named Moses.

“They are all important. We are intensely interested in all of them,” Villiers wrote. “The small Australian Persian kitten is the animal ‘boss’ of this kingdom; his word is law even to the three pigs, which he religiously chases every morning from the galley door, where they grunt at the cook for food.”

During the day, Kirri took naps in the captain’s hat, and in the evenings played with him on the poop deck (the one that forms the roof of a cabin in the rear of a ship). “I believe if Kirri went overboard we would put out a boat and go after him, no matter what the weather was like,” Villiers observed.

Sullivan shares another story of sailor-cat love: Mrs. Chippy, a tiger-striped tabby taken on board the Norwegian expedition ship Endurance by Harry McNish, the boat’s carpenter (whose was nicknamed “Chippy,” as many shipwrights were).

Mrs. Chippy—who kept the name even after turning out to be male—walked, to the crew’s amazement, along the ship’s inch-wide rails in even the roughest of seas. When Endurance was famously trapped in pack ice in Antarctica in 1915, and captain Ernest Shackleton decided to abandon ship, he also resolved to shoot the “weaklings” on board—including several sled dogs and Mrs. Chippy. He wrote in his journal:

This afternoon Sallie’s three youngest pups, Sue’s Sirius, and Mrs. Chippy, the carpenter’s cat, have to be shot. We could not undertake the maintenance of weaklings under the new conditions. Macklin, Crean, and the carpenter seemed to feel the loss of their friends rather badly.

McNish reportedly never forgave Shackleton, even after their near-miraculous escape and rescue, and was denied the Polar Medal awarded to most of his fellow crewmen because of his attitude. In 2004, the New Zealand Antarctic Society built a life-size bronze statue of Mrs. Chippy, also featured on local stamps, on McNish’s grave in Wellington.

Today many countries no longer allow animals to work officially on ships, but, Sullivan explains, that does not stop maritime workers from picking up stray cats in ports. The long-standing tradition of maritime pets remains alive and well, however, among pleasure cruisers. One of the most famous examples is probably Monique, a hen that is traveling around the world with her owner, Frenchman Guirec Soudée, who in 2014 set sail from his native Brittany aboard a 39-foot boat named Yvinec.

“Compared with people, she doesn’t complain at all,” Soudée told BBC News in 2016. “She follows me everywhere, and doesn’t create any problems. All I need to do is shout ‘Monique!’ and she will come to me, sit on me, give me company. She is amazing.”

“The more I do research on this, the more I realize how much pets meant to sailors,” Sullivan says. “And this field is finally attracting attention from scholars too.” She cites a two-day international conference on maritime pets that will be hosted by the U.K.’s National Maritime Museum in Greenwich in 2019. As explained in its call for papers, the conference will seek to “shed fresh light” on maritime history by focusing on animals, which are “too often absent, or marginalised in passing references” in traditional maritime narratives. “I knew that there were a number of scholars working on this subject,” Sullivan concludes, “but the fact that they will host a whole conference on this suggests it’s almost becoming mainstream.”

* Correction: This article was updated to correct Sari Mäenpää’s current affiliation.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook