Are Double-Sided Graves the Solution to London’s Burial Crisis?

Toward a new definition of eternity.

In 1894, the two-year-old son of Marion and Robert Crawford died in the East London district of Stepney. When they buried Robert Jr. in the city’s only publicly run cemetery, the Crawfords had planned, eventually, to join him there. They purchased a single plot, and dug deep enough to accommodate multiple future burials, so that their coffins could be stacked atop their son’s. The lettering across the top of the headstone makes their intention quite clear: “The Family Grave of Robert and Marion A. Crawford.” But they never did join their son. Perhaps they moved away. Perhaps they died in anonymity, with no further children to arrange for their burial.

Robert Jr. now shares his narrow, subterranean space with a complete stranger. His headstone has been turned around, and a new name has been added to it. With no further burials after Robert Jr.’s, the Crawfords’ grave was considered abandoned. And at the City of London Cemetery & Crematory, abandoned graves do not stay that way.

This curious, double-sided headstone is just one of many shared graves with surprising backstories. Staff at this cemetery bury newcomers on top of long-term residents, flip the headstones around, and inscribe the names of the more recently deceased on the opposite side for all to see.

Dying in London is not cheap. You can expect your family and friends to cough up a colossal sum for a small patch of grisly real estate (easily over $15,000), or to travel a serious distance to visit your grave. One third of London’s inner-city boroughs have zero—as in, none—available grave plots. With space dwindling and costs rising, people are increasingly warming to the idea of reusing burial plots. It may be the only way to maintain burial traditions and keep the dead close to the living.

Behind the growing popularity of grave reuse is a man named Gary Burks. Burks’s family moved into a house inside the City of London Cemetery walls when he was six, after his father got a job digging graves and mowing the grounds. Now in his 50s, Burks is the site superintendent. He and his team have made it their mission to make burial sustainable, without having to expand, and thereby put out living Londoners. “Any land that’s suitable for burial is also suitable for housing,” he says. “And we have a housing crisis as well.”

London has struggled to fit both living and dead within city limits for two centuries. The metropolis’ population skyrocketed with the Industrial Revolution in the first half of the 1800s, and that meant more dead bodies. The city’s graveyards—most of which were in the yards of neighborhood churches—couldn’t keep up. Mourners watched as overworked gravediggers dismembered dead relatives to cram them into tiny spaces. Heavy rains exposed coffins shoved hastily in shallow graves. City-dwellers stepped right into some graves, through the loosely-packed soil cast atop them. Gases from rotting corpses had to be “tapped” by undertakers to prevent explosions. Some cemetery workers even died while doing this, choked by putrescent fumes.

So wretched had the situation grown that in the 1830s Parliament promoted the establishment of seven large, privately run cemeteries on what was then the edge of the city. These “Magnificent Seven” include now-famous destinations such as Highgate Cemetery and Kensal Green, where tombstone tourists can pay respects to the likes of Karl Marx and Mary Ann Cross, the author better known as George Eliot.

But these cemeteries weren’t made for the masses—from the very beginning they were expensive and exclusive. In 1856, the publicly run City of London Cemetery opened as an affordable—and popular—alternative. Too popular, in fact. “In those early days, especially when there were cholera outbreaks, we were burying 9,000 people a year,” says Burks. That’s nearly 25 burials every day. The public graveyard quickly had to expand.

Many of London’s extravagant private cemeteries that made a killing off the flashiness of the Victorian era were finding it hard to stay afloat by the 1940s. Their land was nearly full, and the city had grown to engulf them. No new land meant no new burials—and no new income. Add to this the shift away from elaborate funeral rites and toward cremation, and even graveyards with available space fell out of fashion. The grand deathscapes, in some cases overcrowded with bodies, were overrun by nature. In the coming decades, nonprofits would have to step in to maintain some of these spaces as parks and historic sites.

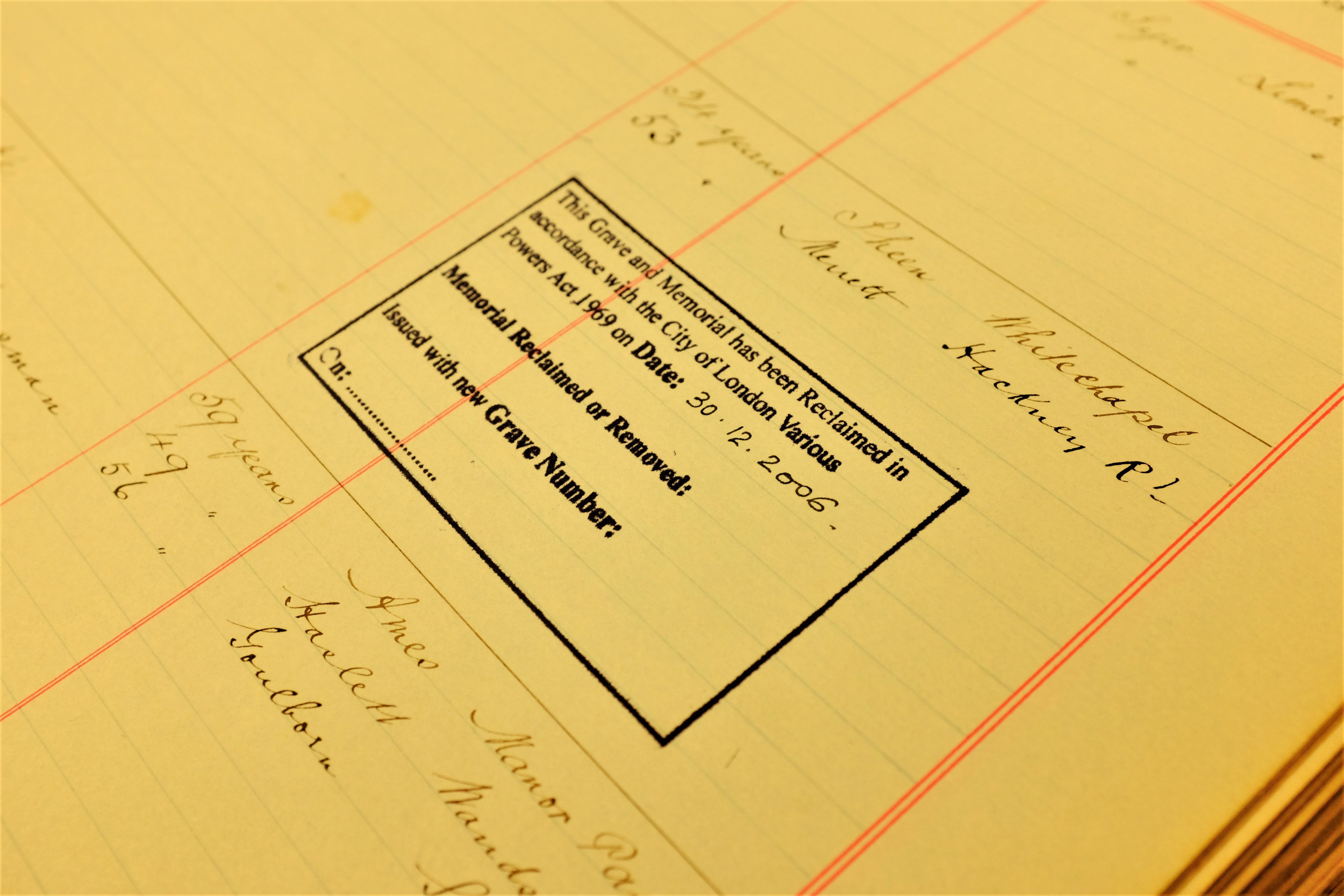

Back then, staff at the City of London Cemetery were quick to take heed of the decline of London’s luxurious cemeteries. “In the 1960s, when we still had loads and loads of space, a superintendent called Ernie Turner saw the risks,” says Burks. The cemetery still needed to make sure that there could continue to be burials, and revenue to sustain operations. Being a public entity, the cemetery pushed a piece of legislation in 1969 that extinguished Londoners’ ownership over their graves after a long period of abandonment. Though putting time limits on burial may seem callous, or not in keeping with the idea of eternity, it was a well-received step toward solving England’s burial crisis. Just eight years later, Parliament passed a law mandating all new grave plots be leased rather than owned, with renewable lease terms ranging from three to 100 years. The City of London Cemetery barely used this authority, which allowed them to retroactively enforce lease terms, until the early 2000s, when another piece of legislation made it even easier to reuse graves. This granted that after 75 years of abandonment—long enough, the staff figured, to be respectful of the dead, but short enough to make reuse sustainable—a grave could get another occupant. At the current rate of burial, Burks calculates that the cemetery can recycle its graves nearly in perpetuity, without needing more land in any foreseeable future.

To be reused, abandoned graves must be deep enough to hold at least one more coffin (eight feet). The only digging required to determine grave depth is in cemetery records. In the locked, fireproof basement of the cemetery’s office building sit 88 large books, each weighing over 55 pounds and together boasting a total of more than 26,000 pages. “In this cemetery I’m very, very lucky,” says Burks. “Because the grave plans are perfectly legible.” Perfectly legible, too, are the columns most important to Burks and his team: the date and depth of the last burial. In this column, Burks and his team found that many abandoned graves have depth remaining for not just one but for multiple coffins, allowing a single reused grave to house multiple family members—or, even, to be reused again, space permitting, after another 75 years of abandonment.

Once graves have been identified as eligible, the staff move on to emotional considerations. They write to all families for whom they have addresses on file that their graves are being considered for reuse. Grounds staff members hang notices on the stones. They post announcements at the cemetery gates and on their website, and buy ads in local newspapers. Then they wait. If a descendant objects any time within six months of these notices, the grave is not considered abandoned and will not be reused for at least another generation. So far, the cemetery has reused roughly 1,500 of its graves.

Customers looking to buy reused grave plots, which are about one third the price of “virgin graves,” aren’t required to reuse the headstone. Legally, the cemetery can throw away a headstone if the lease on the plot below is expired, and some do literally go into the trash. But Burks tries not to reuse graves at the expense of history. “We don’t remove a memorial where we can read the inscription,” he says. “If the memorial is in really good condition … we simply turn the memorial around. The old inscription stays on the back and the new inscription will be placed on the front.” No stone unturned, as they say.

The City of London Cemetery & Crematory has no big names to draw crowds from the posh high streets of the city center, onto the London Overground, and through the unglamorous and sometimes unkempt streets of East London’s Manor Park. But there, amid 200 lush acres and nearly a million bodies (so far), the grave of Robert Jr. and many others have been asked to forgo eternity for the needs of a more immediate future.

In 2012, a London family lowered the body of 80-year-old James Joseph Corbett into the grave space originally intended for Robert Jr.’s parents. “Loving husband, dad, and granddad,” the headstone’s new front reads. “Sadly missed.” In burying Corbett, his family brought an unexpected new chapter to the story of young Robert Crawford, whose memory had been to crumble. And perhaps, somewhere years down the line, another Londoner may join them.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook