The Stories Hidden in Fossilized Mammoth Footprints

What researchers uncovered when they analyzed 43,000-year-old tracks.

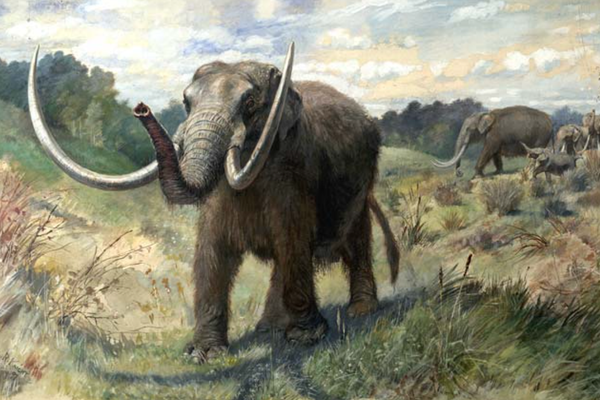

Oregon’s Fossil Lake is not a lake anymore. It’s a flat, barren desert lined with white sand dunes and sagebrush. But the other half of its name remains accurate, as it is a reservoir of prehistoric fossils. Recently, paleontologists from the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, the Bureau of Land Management, and the University of Louisiana excavated Columbian mammoth fossilized tracks from this repository. In a new study published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, they unravel the story behind these prehistoric footprints.

Greg Retallack from the Museum of Natural and Cultural History found the 43,000-year-old tracks in 2014, but it took until now to fully comprehend the 117 footprints. (You can see the trackway in the video below, prepared by Dean Walton, science and technology outreach librarian at the University of Oregon.) In July 2017, the team used an advanced technique called photogrammetry to create an image of the tracks that was true to scale and measurements. According to a press statement, the team could “see the minute differences and similarities in both the trackway’s prints and the surrounding surface,” and analyze what the footprints say about the Ice Age animals.

Based on the size and depth of the imprints, the researchers suggest that a herd of at least six mammoths traveled west on volcanic soil towards a local watering hole. There were four large imprints, indicating adult-sized mammoths, and one medium-sized imprint, likely belonging to a juvenile. Lastly, there was one small imprint, from an infant. However, one main set of footprints caught the researchers’ attention.

This set contained 39 prints and was 66 feet long. “These prints were especially close together, and those on the right were more deeply impressed than those on the left—as if an adult mammoth had been limping,” said Retallack in a statement. In an interview, he infers this mammoth might have suffered a life-threatening injury.

Medium- and smaller-sized footprints tended to converge and diverge around the adult mammoth imprints. Retallack surmised that these belonged to the teenage and infant mammoth, who followed the adult “repeatedly throughout the journey, possibly out of concern for her slow progress.”

How did the team know this injured Columbian mammoth was female? The team relied on research about mammoths’ close relatives, the Asian and African elephants, as evidence for this theory. According to a 1998 Animal Reproduction Science study, when an elephant is wounded, members of a matriarchal herd will follow the injured elephant to make sure it is okay. Based on the young mammoths’ footprints around the main trackway, the researchers concluded that the injured member of this herd was most likely a female, although not the leader herself.

“It was a matriarchal group, mainly females,” says Retallack. “One of the others in the group might have been the matriarch, but we don’t have any evidence of her.”

Kristin Strommer, the communications manager for the Museum of Natural and Cultural History, adds that the team confirmed the injured mammoth’s sex and age with “comparisons to modern-day African elephants using biological models to scale elephants to the size of a mammoth.” According to this modeling, the hurt adult was 11 years old, and on the brink of death.

Another part of the story is how the extinction of these megafauna, which once roamed North America thousands of years ago, affected their environs. Fossil Lake used to be surrounded by water and lush with lowland grass. “Mammoths were grazers dependent on grasslands for food,” says Retallack, and the grass relied on mammoth dung for fertilization. The disappearance of the mammoths may have been a contributing factor to the desertification of Fossil Lake and other lake basins in this part of Oregon. “Grasslands went away once the Columbian mammoths went extinct,” Retallack says.

Though these mammoth tracks existed long before mammoth extinction, as Strommer puts it, “the tracks are interactions preserved in action.” They tell us how mammoths once reigned.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook