A Botanical Mystery Solved, After 146 Years

How a young illustrator’s attention to detail—and a determined Victorian woman’s legacy—led to the discovery of a new species in an old painting.

Something about the painting made Tianyi Yu pause. The artwork, depicting tropical plants crowded together in a riot of color, had been painted in 1876 by prolific botanical illustrator Marianne North. The wealthy Victorian woman had traveled the world, usually on her own, documenting in bold oils the plants and landscapes she saw.

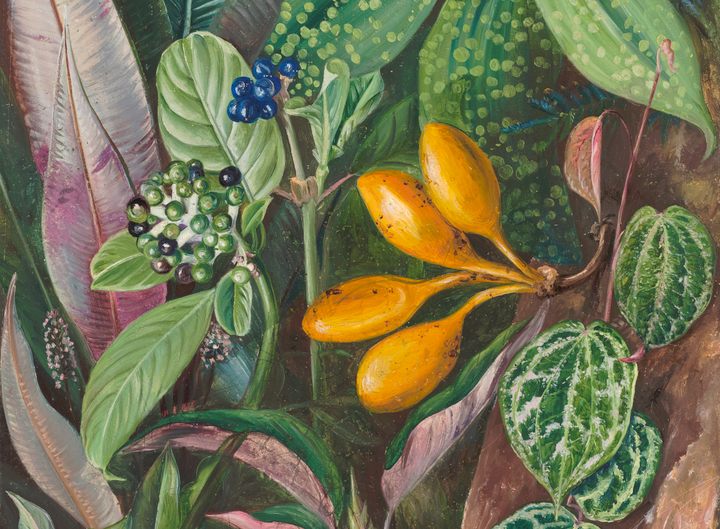

During a trip to Borneo, North had filled this canvas with plants from a particular spot in the forests of the island’s northwest corner. The viewer’s eye might be drawn to oblong yellow fruits from one plant, or pink buds from another, or the rounded leaves cascading down one side of the painting, one of them apparently nibbled by an insect. But Yu, a botanical illustrator who was working at London’s Kew Gardens while pursuing a masters degree, was drawn to clusters of berries, some green and unripe but others black or a bold blue. These berries would solve a botanical cold case more than a century in the making, and connect both illustrators forever.

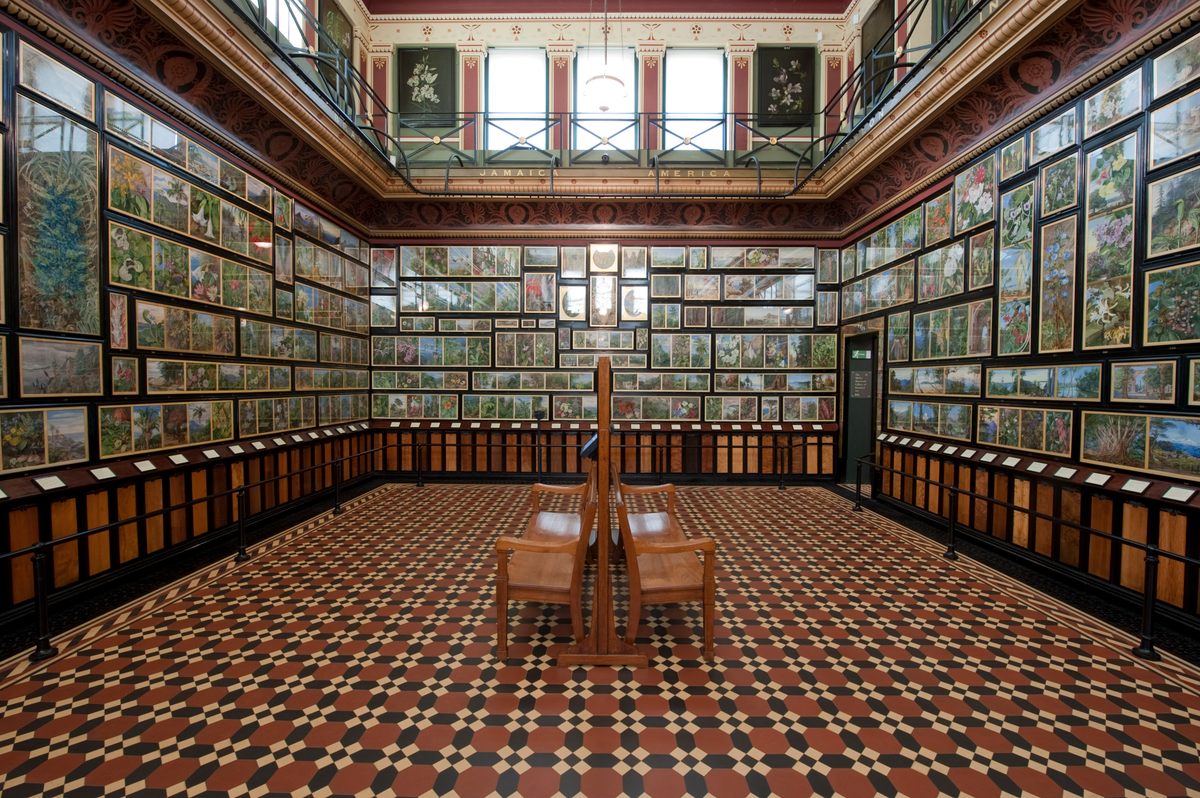

The painting, known as Curious Plants from the Forest of Matang, Sarawak, Borneo, was just one of more than 800 works lining the walls of Kew’s Marianne North Gallery, which occupies its own building on the gardens’ extensive grounds. The gallery opened in 1882, after North had arranged for its construction and meticulously supervised its design, down to selecting and ordering the wood for the dado, or chair rail, that runs around the main room. Such attention to detail was part of everything North did, including her painting of those curious plants of Sarawak that had stopped Yu in his tracks.

“There was no plant name in the title of the painting, and the description of this painting was unclear,” Yu writes in an email from Beijing, where he now works as a freelance botanical illustrator and researcher. He was particularly drawn to the shrub-like plant bearing those small, blue berries. An earlier description of the painting had attributed the plant as Psychotria, also known as wild coffee—but Yu knew such a color is not present in the genus. He also knew it wasn’t a case of North taking artistic license. She always painted exactly what she saw, including the habitat in which the plants lived, using oils—unlike her contemporaries, who typically painted single specimens, isolated on a neutral background, using thin layers of watercolors.

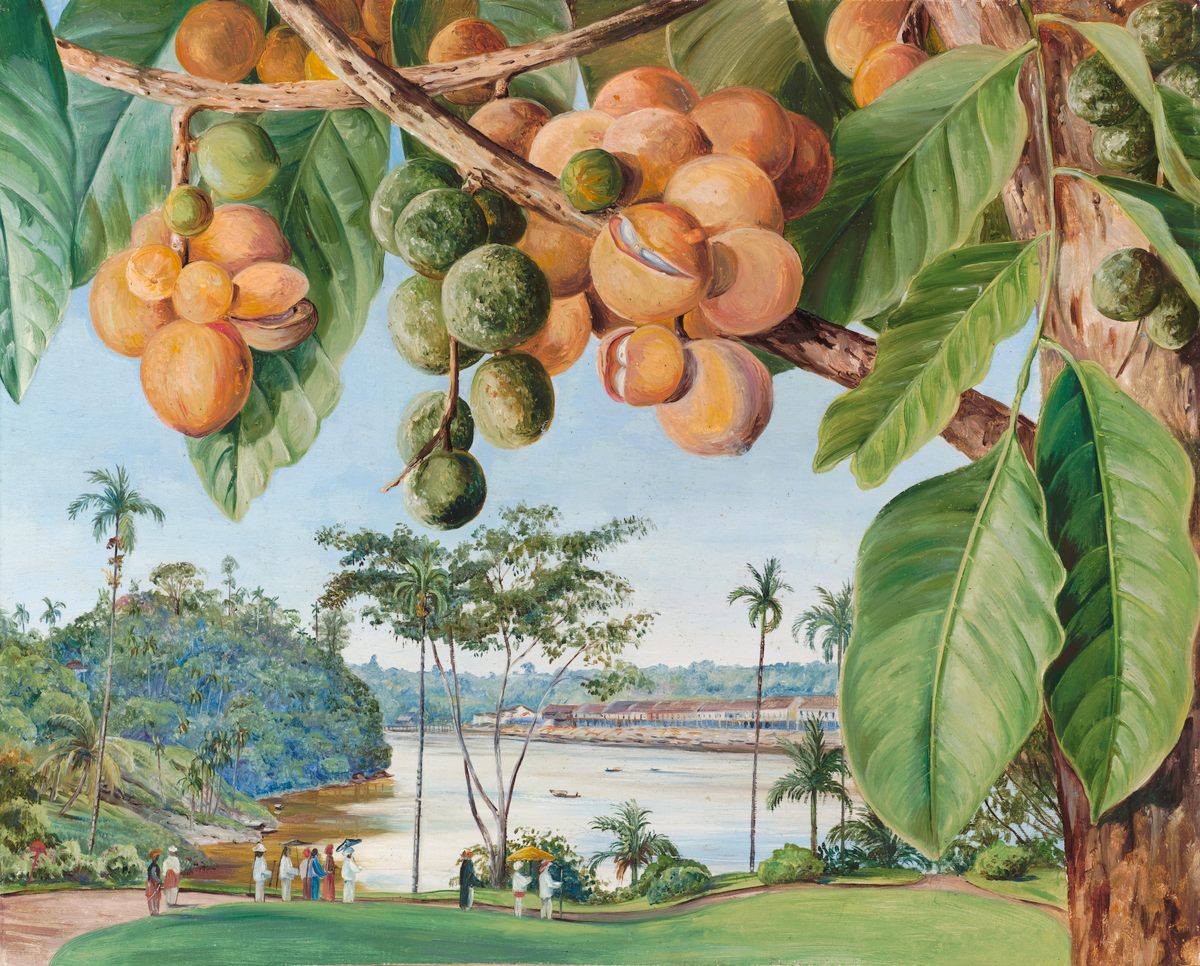

“It’s a very distinct style, absolutely,” says University of York art historian Philip Kerrigan, who contributed a chapter about North’s botanical illustrations to a recent academic overview of women in science. “It’s partly the oil medium but it’s also the composition of things. She’s got an interest beyond that of the botanical artist whose paintings fulfill a specific scientific purpose, with various closeups of the stamen and such. It’s her interest in the ecological relationships, in the environment.”

Critics of the day were often not impressed with North’s paintings, says Kew senior conservator Jonathan Farley. One curator of a rival gallery declared her work “universally gaudy.” But North’s style proved to be valuable to science in a way her contemporaries’ isolated watercolor studies were not.

“Today, when specimens are collected, the GPS location of the collected item is recorded with the data,” says Farley. “In Marianne North’s time, the level of accuracy was that bamboo came from Southeast Asia, hemp came from India, and pitcher plants came from Borneo. By depicting plants in their natural settings, not only did Marianne tie down exactly where they grew, her paintings also indicated the environmental conditions they grew in. She was one of the first people to add information about ‘where’ and ‘how’ to botanic knowledge.”

North didn’t start out as a bold oil painter of tropical plants in their ecosystems. Born in 1830 to a wealthy family in Hastings, she was the eldest daughter of Frederick North, a Member of Parliament. Her privileged upbringing included lessons in landscape watercolors, vocal training, and other undertakings typical of young women of high society at the time, as well as some less conventional activities. She traveled widely through Europe and the Middle East with her beloved father, who encouraged her interest in the natural world. She was introduced to painting landscapes with oils and, says Farley, “In her diary, she says that she took to oils like a ‘Scotsman does to dram-drinking.’” The richer, more intense colors seemed a good fit for the confident, inquisitive woman.

Then, when she was 40, North’s father died. Even in grief, she persevered. After a stay in Sicily to paint, she traveled to the other side of the Atlantic and embarked on a formative train journey through the United States and Canada. “It appears that it was her viewing the bright colors of nature on this journey that caused her to decide to paint plants in their natural settings,” says Farley.

As North’s style and focus evolved, the scope of her travels expanded. She spent a year in Brazil and extensive periods in Japan, Sri Lanka, Borneo, and beyond, usually on her own. When she was back in England, she often put on public exhibitions of her work, and became a bit of a Victorian influencer.

“If you look at the newspapers of the period, there are more reports of what Marianne was up to than what most male explorers were doing,” says Farley. “I think that part of the reason that there was so much interest in Marianne was because she was going alone to places that society believed women simply shouldn’t go.”

Farley praises “the sheer determination she had to not conform to society’s ideas on how women should behave.” But Kerrigan, another admirer of North, says she was also very conscious of the privilege that afforded her the opportunity to chart her own course—and the limits, placed by society, she could not escape. He believes that self-awareness was a factor in her public promotion of her work.

“She was working at a time when botany was becoming increasingly professionalized, and those kinds of professional spheres largely excluded women,” says Kerrigan. “She did have to work twice as hard to make her work stand out and be distinctive.”

In addition to the challenges of being a woman, North faced other prejudices in her quest to be taken seriously. “She was always conscious that she had this money, and was concerned people would think she gets these things because she pays for them, or because of her social standing,” says Kerrigan. “She wanted to earn it on her own merits.”

Her painting style also bucked the convention of the day, and not just because she used oils. North embraced elements of the Impressionists, including their use of shadow and light, and, critically, their penchant for painting outside, rather than in a studio.

“(During) that period, painting in oils ‘en plein air’ was considered uncouth to all but the Impressionists, but Marianne preferred to paint in this way,” says Farley, who played a leading role in the 2009 restoration of the gallery that bears her name. “Granted, we did, on occasions, find an insect head, or a bit of twig in the painting when we did the conservation work on them.”

It was North’s lack of conformity that has made her work so significant, then and now. No less than Charles Darwin, who admired North and her talent, urged her to travel to Australia to document its flora for science. During her time in Borneo, her painting of a pitcher plant was rendered in such detail that it was determined to be a new species; it was formally named Nepenthes northiana five years later, one of four species named in her honor.

Nearly 150 years after her time in Borneo, a fifth species would bear her name—but only after Yu did some detective work, starting with a closer look at North’s 1876 Curious Plants. He suspected that the plant with blue berries might have been a member of the genus Chassalia, thanks to North painting it “very carefully, catching some of the most important structures of this species.” Many species in the genus, widely distributed from Africa to Southeast Asia, are poorly documented, and known only through brief field descriptions rather than images.

Working with his supervisors, Yu decided to compare the plant in the painting with specimens from Kew’s extensive herbarium, which houses roughly seven million specimens collected from all over the world. His endeavor was made much easier thanks again to North’s attention to geographic detail: He was able to narrow his focus to plants collected from the Matang Forest in Sarawak, and found a specimen collected in 1973—just shy of a century after North painted the plant in its natural setting. In 2021, Yu named the newly identified species Chassalia northiana. It’s North’s latest, but likely not her last, contribution to science.

“It is still very hard to go to all the places she visited, even in this day, and some places she visited still lack scientific survey,” says Yu. “There are still many species in her paintings without information or a photo, or even a scientific name, so the paintings are still very important for scientific research.”

North, who died in 1890, created a lasting scientific legacy—one that continues to inspire. “As a botanical illustrator, I think Marianne North was a pioneer who achieved both scientific accuracy and visual appeal,” says Yu. “[Her] paintings are inexhaustible treasure.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook