An Adorable Algae Ball Mystery Has Been Solved

Sometimes marimo float, and sometimes they sink. But why?

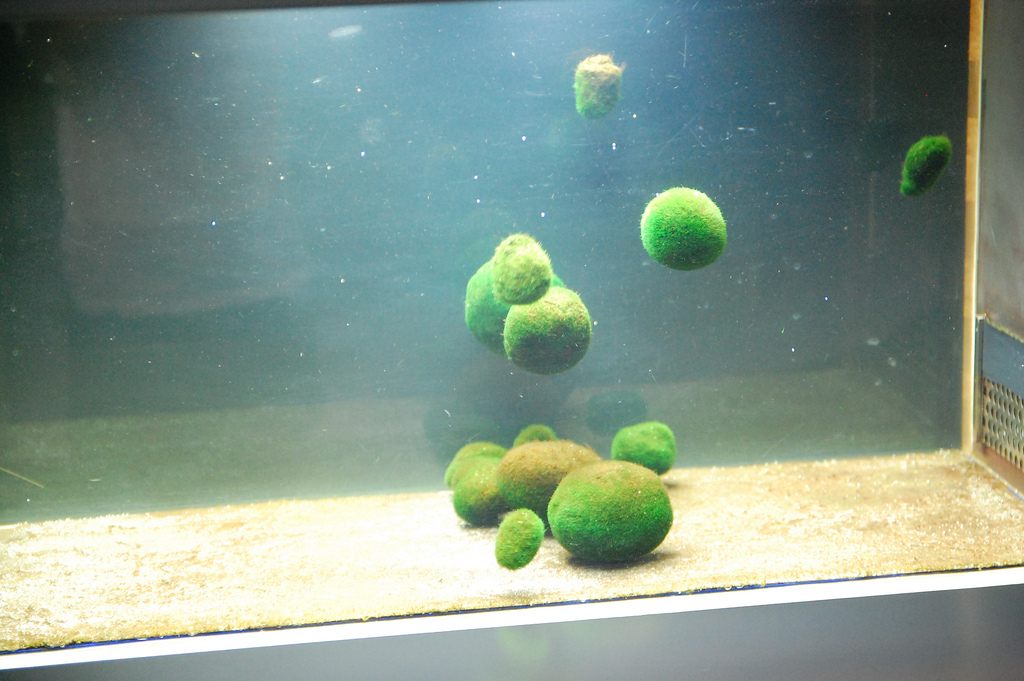

Marimo might be the cutest plant on Earth. It’s round, bright green, and fuzzy. It even dances, albeit slowly: In the morning, marimo balls float to the top of lakes, and at night, they sink back down again.

It’s tempting to raise the plant up to your cheek and ask, “Why do you do that, little buddy?” (Do not do this: In many areas, marimo is a protected species.) But it took new research from the University of Bristol to actually figure it out.

Marimo balls may look like autonomous mini-muppets. But they’re actually made up of a green macroalga called Aegagropila linnaei. In many environments, A. linnaei acts like more typical algae, growing on top of rocks and shells or floating around in the water in small pieces. But sometimes, scraps of the algae meet and get tangled up in clumps. Under certain conditions, these clumps grow large and sink to the bottom, and the motion of the water pushes them back and forth over the sand like a kid with a snowball, sculpting them into spheres.

The balls make an impression wherever they show up, which is generally in shallow, sandy lakes in the Northern hemisphere. Lake Svityaz in Ukraine has them, as does Lake Mývatn in Iceland, where fishermen named them Kúluskítur, or “round shit,” because they’d get tangled in their nets.

There are so many of them floating in Japan’s Lake Akan that they’re the subject of an annual Marimo Festival, which has been held since 1950. They are also popular among aquarium aficionados—so much so that people sell fake ones, made of styrofoam wrapped in java fern.

For this new study, which was published in Current Biology, the researchers brought some aquarium-grown marimo balls into the lab. First, they wanted to test a theory about why they float: namely, that when the algae photosynthesize, they exhale tiny bubbles of oxygen, which catch on the ball’s tendrils and pull it up to the water’s surface. The researchers coated a group of marimo with DCMU, a chemical that stops photosynthesis, and put them inside graduated cylinders. When they exposed these balls to light, they didn’t blow bubbles or float. Instead, they stayed stuck at the bottom of their tubes.

With that settled, the researchers went on to test whether the marimo balls float more readily at certain times of the day. They first got them on a particular “sleep” schedule, exposing them to 12 hours of light followed by 12 hours of darkness. Then they put them in dim red light for a while, to try to throw them off. But it didn’t work: When the researchers flicked a bright light on in the morning, the balls popped up much more quickly than they did in the afternoon. (Many plants have circadian rhythms like this, which help them know the best times to grow, flower, and photosynthesize.)

Natural marimo balls are rare, and getting rarer—a 2010 study found that their populations are declining worldwide. Those researchers pinned the problem mostly on eutrophication, or an excess of nutrients that other plants and algae feed on, crowding the water.

University of Bristol researchers hope that figuring out these balls’ behavior might help save them: “By understanding the responses to environmental cues and how the circadian clock controls floating, we hope to contribute to its conservation and reintroduction in other countries,” lead author Dora Cano-Ramirez said in a press release. In the meantime, keep dancing, little cuties.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook