This Orlando Water Park Is Wild. No, Really.

At Orlando Wetlands Park, water goes for a ride—through a natural filtration process—and attracts birds, gators, and more.

Just over half an hour east of Orlando’s many theme parks, there is an altogether different kind of attraction, even though it exists because of those fiefdoms of fun. You won’t find parades, souvenir shops, or any towers of terror—but you might witness talons of terror, as bald eagles take on alligators in a real-world “Duel of the Fates.”

Orlando Wetlands Park—formally known as Orlando Easterly Wetlands—is more than 1,600 acres of different types of marsh mixed with forest and a lake. Winding rows of levees and berms throughout the park are your first clue that this is not nature’s work. In fact, the site was engineered in the 1980s, creating a diverse set of wetland environments on land that was previously a dairy farm.

While Orlando Wetlands Park is manmade, don’t confuse it with Seven Seas Lagoon and other artificial “wilderness” spots in the theme parks. This birder’s paradise—also a spot popular year-round with nature-lovers and scientists alike—plays a crucial role in the greater Orlando metropolitan area’s infrastructure.

At this park, it’s not the tourists who go for a ride, it’s the water.

The park exists because rapid development in and around Orlando over the last half-century has required expanding the area’s wastewater treatment infrastructure. Since 1971, when Walt Disney World opened, the area’s population has increased more than five-fold to well over two million people—and that’s not counting the roughly 60 million tourists who visit each year.

Built in 1987, the Orlando Easterly Wetlands Reclamation Project was on the cutting edge of wastewater treatment at the time, and was not only one of the first but also one of the largest such filtration projects in the world. The midcentury approach to treating wastewater as quickly as possible, often subjecting it to a barrage of artificial chemical processes, was falling out of favor. Instead, engineers had begun designing facilities that rely on slower methods that replicate what happens in nature.

Every day, up to 35 million gallons of metropolitan wastewater, collected at a separate facility about 17 miles away, travel via underground pipes to Orlando Wetlands Park. There, the incoming water is diverted into three “flow trains,” or paths, taking it through 18 different “cells”—ecologically diverse areas divided by levees, berms, and other structures. Just as a tour of EPCOT takes you from one country to the next, water passing through the artificial wetlands gets to experience different micro-environments.

For example, the park’s 400-plus acres of deep marsh, thick with bulrush and cattails, are an early stop on the water’s ride. There, both plants and a variety of microbes, including algae, feast on phosphorus, nitrogen, and other unwanted chemicals in the wastewater. The water, now a movable feast, travels next to a mixed marsh environment dominated by aquatic plants such as duck potato and southern naiad, followed by a swampy forest of water hickory, cypress, and pop ash. Depending on which flow train it follows, the water may also spend time in roughly 100-acre Lake Searcy.

While toxic algal blooms have wreaked havoc along parts of Florida’s coasts, natural, healthy communities of algae are among the hardworking heroes at Orlando Wetlands Park. Staff monitor the water’s quality regularly to ensure the tiniest workers in the city’s infrastructure aren’t slacking on the job. About 30 to 40 days after the water arrives at the park to start its wild ride, it’s fully filtered and flows via canals into nearby St. John’s River.

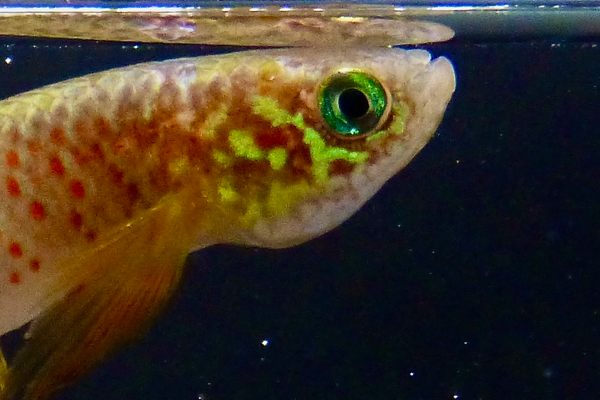

The park’s wetlands have improved water quality for the river, but they’ve also created an attractive home for wildlife, including alligators, bobcats, river otters, and more than 230 species of bird. (There have also been claims of the occasional black bear and Florida panther passing through.)

The rich biodiversity of the park can sometimes lead to unexpected drama. In April 2023, horrified visitors witnessed an adult alligator attack a young bald eagle. A few months earlier, the tables were turned when a great blue heron was photographed scooping up a baby gator as its desperate mother tried to stop the steal. Hey, it’s the Circle of Life, whether you’re a microbe gorging on wastewater or a bird looking for lunch.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook