What the Dodo Means to Mauritius

The extinct bird is a national symbol. But why?

Dr. Vikash Tatayah, the conservation director of the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, has a decidedly morbid picture hanging on his office wall. It’s a copy of a wood cutting from 1604, etched just a few years after Dutch explorers first arrived on this secluded, unpopulated island in the middle of the Indian Ocean. In the foreground, sailors lure Mauritian grey parrots from the treetops, then grab them by the wings. Further down the beach is pile of dodo corpses, with more birds being clubbed to death beside them. Ships wait on the horizon, harbingers of the destruction to come. Less than a century later, the dodo would be extinct.

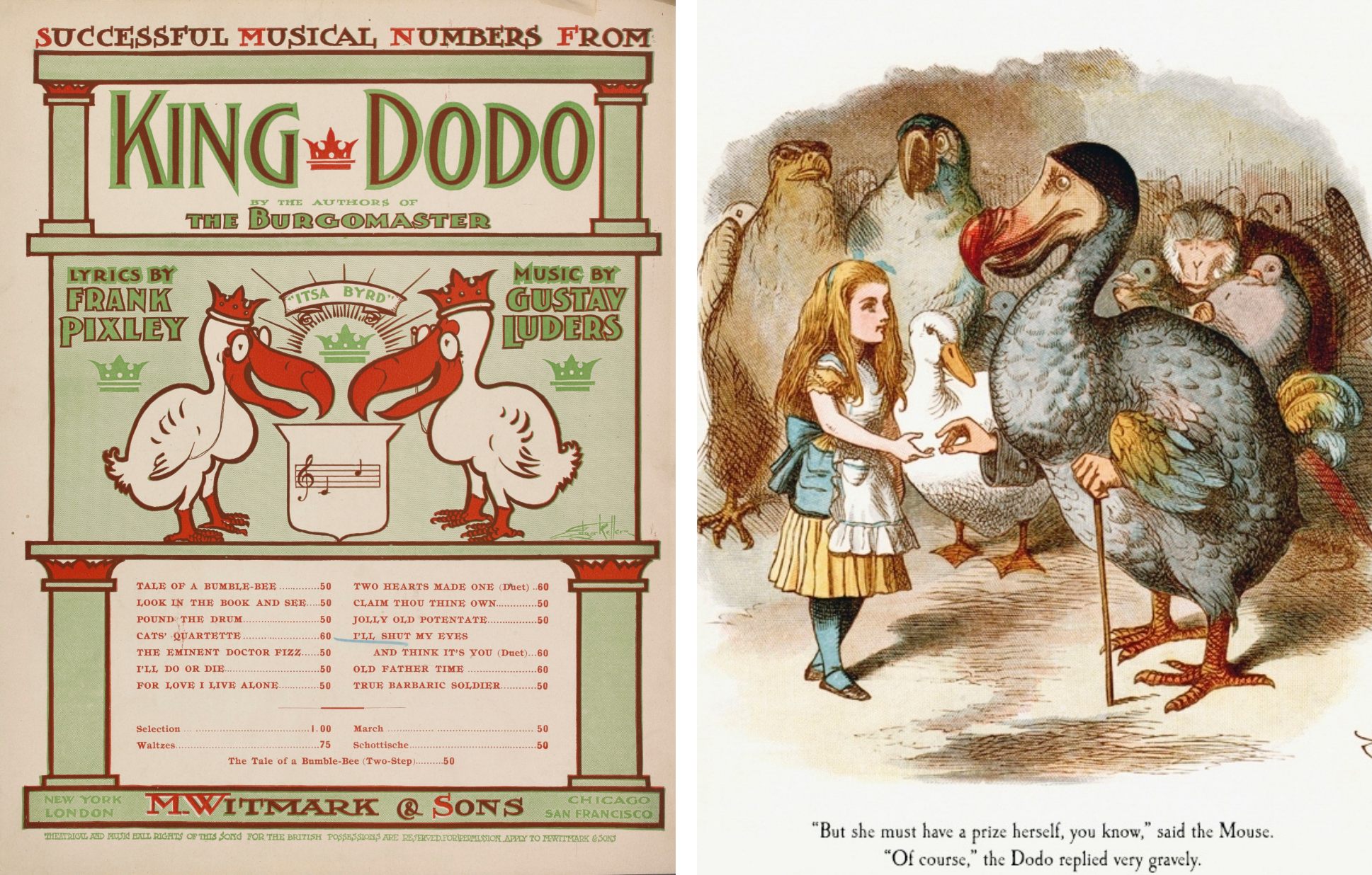

Tatayah’s office décor is appropriate for someone devoting their career to saving the island’s remaining native species. But it stands in stark contrast to the near-ubiquitous image of the dodo, displayed across Mauritius, as a kind of jolly national mascot. Its roly-poly, beaked visage is given place of pride on the country’s currency and customs stamps and national seal. The dodo lends its name to pizza parlors and coffee shops, its likeness to beach towels and backpacks. There are giant dodo statues in public parks and mall food courts. Countless tourist shops hawk tiny carved dodos for a few dollars. If you’d like a more rarefied version, you can pick up a pair of figurines from Patrick Marvos, an upscale jewelry shop near the botanical gardens, in sterling silver, price upon request.

Despite the polar images of the dodos dying on a beach and the dodos grinning in a shopping mall, it would be reductive to plot Mauritius’s relationship to the creature along a binary axis of shame and pride. The dodo has become a symbol of national identity in Mauritius, a kind of synecdoche for the island and its relationship to its colonial past.

Some Mauritians traveling abroad find the extinct giant pigeon is the only thing people know about their homeland. In 2015, Mauritian Rick Bonnier came to the United Status as part of a State Department exchange program for young African leaders. On his travels through North America, he often encountered people who couldn’t find Mauritius on a map.

“I told them ‘the dodo birds,’” he says. “And then it kind of comes back.”

Though the dodo may be now synonymous with a kind of cursed stupidity (“going the way of the dodo” is a cliché on Mauritius as much as it is elsewhere) it did not waddle dumbly into extinction. They were naïve, but not without reason; after all, they had never met a predator. There were, aside from fruit bats, no native mammals on Mauritius. The Dutch did become dodo predators, but contrary to the popular perception, did not hunt the bird into extinction. When they did eat them, it was not very happily; the meat was, according to contemporaneous reports, tough and unappetizing. The Dutch called it “walghvoghel,” which translates roughly as “tasteless” or “sickly” bird, because the flesh was so unctuous that it made the sailors ill.

The real problem was less the humans than what they brought with them. Cats, rats, monkeys, pigs, and other animals the colonists imported by accident or design were likely the ones who killed the bird off by feasting on its eggs and competing with it for food and resources. At a time when species around the world are facing similar threats, the dodo remains a bracing metaphor for ecological degradation—just not the way that we think. As is often the case, the dodo died not primarily from overt human villainy—blood-thirsty sailors thwacking birds on the beach—but rather by the all too human failure to consider the secondary effects of our actions—stowaway cats and rats—until it is too late to reverse them.

Dr. Tatayah and his organization have taken the lesson of the dodo to heart. Overshadowing the cautionary woodcut in Dr. Tatayah’s office are images of the other species Mauritians have brought back from the brink, with their growing numbers written beneath their pictures. But humans are still driving creatures to extinction on Mauritius, or at least coming close. Martine Goder, who works with Dr. Tatayah on the Island Restoration program, explains that even today, with biosecurity checks and public education, human settlement still poses dire, if accidental, threats to native ecosystems. Within the past decade, for example, shrews snuck in with construction materials onto Flat Island off the north coast of Mauritius, home to the last remaining population of orange tail skinks. The reptiles are tiny, skinny as an adult’s thumb with a long, snaking body that fades from brown to bright orange along their eponymous tail.

“Within 15 months,” Goder says, “all the reptiles had disappeared.” Conservationists managed to save some remnant of the population that used to number in the tens of thousands and move them to a nearby predator-free island. “But if this hadn’t been done,” Goder says, “we would have lost a species in 2011 in Mauritius.”

The loss of the skink would have carried a different emotional valence than the disappearance of the dodo. Like the dodo, it would have died not so much through direct human villainy as a kind of carelessness or neglect. But it would have been the “fault,” so to say, of the Mauritians themselves, rather than distant colonists. Perhaps this is why Goder and others, even those in the conservation world, don’t have that same ferocity when discussing the dodo as they do other Mauritian species.

Sidharta Runganaikaloo co-founded SYAH (Mauritius), an environmental NGO, on the island and acknowledges the dodo bird as a symbol of her country. She says when she first saw a link to The Dodo, the American site providing, in its words, “visually compelling, entertaining, highly shareable animal videos and stories,” she at first assumed it had to be a new Mauritian news site, based purely on the name.

But even with the close association between her country and this creature, she still feels a kind of distance.

“I’ve learned about the dodo in history class,” Runganaikaloo says. “You know that it’s the national animal of the country and… it’s just that. At the end of the day, I don’t feel any emotional belonging.”

Mauritians are all the descendants of immigrants. There were no ancestral myths about the dodo, no home remedies made from their flesh, no superstitions around their sightings, no one passing down any stories at all, other than European colonists arguing over whether or not it existed.

This dearth of a mythological record is because, when the Dutch touched down in 1598, they found an uninhabited island, unusual in the dark history of colonialism. Mauritius wasn’t fully settled until 1638, when it became an outpost of the Dutch East India Company. Their plan was to harvest the ebony forests by the sweat of imported slave labor, mainly from Madagascar, since there were no native Mauritians, aside from the forests and the animals, available for exploitation.

The last dodo sightings were reported in the 1680s. Less than 30 years later, the Dutch abandoned the island. By the time the French claimed Mauritius in 1715, the dodo was gone. Even the descriptions that survived were not granted much respect: The bird’s location was so remote and its physical appearance so unusual, that people dismissed sightings of it as mere fantasy, on par with “the Griffin or the Phoenix,” as the British naturalist H.E. Strickland notes in his 1848 book The Dodo and its Kindred. It was only in his account, written well after the British had seized Mauritius, that the dodo’s disappearance was truly recognized.

“These singular birds,” he writes, “[…] furnish the first clearly attested instances of the extinction of organic species through human agency.”

Though Strickland ultimately couched his description in the language of religion, it was still a significant admission of human guilt. While the dodo was not the first species we had eradicated, it was the first one to enter, albeit belatedly, the popular consciousness as a source of human shame.

“This is the bird of conservation,” says Dr. Tatayah, the Mauritian ecologist who keeps the aforementioned 17th-century woodcut pinned up by his desk. “Previous to that it was ‘nature is abundant, nature provides for man, nature is bountiful.’ But this was the first time that man realized well, actually you can drive things to extinction.”

Perhaps it is the distancing effect of Mauritius’s colonial history—the idea that “they” killed the dodo and not “us”—that makes the popular image of the bird so mordantly jolly. Perhaps any animal that is dead for that long inevitably feels too distant to elicit much feeling. But there was one dodo reference, out of the dozens one sees across the island, that may best encapsulate the island’s relationship with its original resident.

At the end of the tour through the L’Aventure du Sucre, the museum in Mauritius dedicated to the long history of sugar cultivation on the island, there is a cartoon. In it, a tourist couple stares, panel by panel, at meeting places for Hindus, Muslims, Creoles, Chinese, whites, the full melting pot of Mauritian heritage. In the final panel, seemingly exasperated, they ask a man where they can find “the real Mauritians.” He tells them, in so many words, that they’re looking at them. There are no “real Mauritians.” That’s just a sales pitch for tourists.

But behind him, a little gray dog pipes up: “Les vraies Mauriciens ont été mangés par les Hollandais il y a longtemps.”

The real Mauritians were eaten by the Dutch a long time ago.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook