The Artist Who Sees Vintage Medical Devices as Sculpture

A Chicago gallery showcases haunting pieces of medical and dental history.

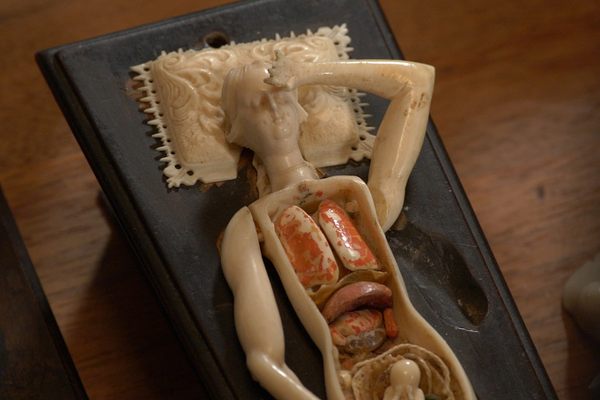

What you are looking at, in the photo above, are dental phantoms. They are not meant to be ghoulish; they are meant to train dentists. But there’s no denying that they are striking, memorable objects. Which is exactly what attracts Mariano Chavez to them.

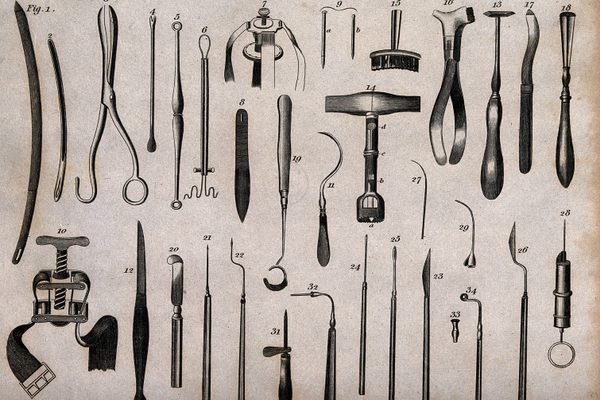

Chavez is the founder and proprietor of Agent Gallery Chicago, a collection of medical tools, dental mannequins, and other unique objects. As an artist, Chavez is drawn to these vintage medical devices both for their sculptural qualities and for their particular uses. While his initial attraction to a piece is always based on its appearance, he says, “I like that people apply some sort of training and understanding to these objects.”

Chavez started gathering these medical oddities after graduate school, when he was working with a friend on architectural salvage. Often, they’d go through hospitals, and little by little Chavez started collecting pieces of medical history.

“Initially I was more into collecting. I would keep a lot of the pieces,” he says. “Now I keep them for a little bit, I document them, I make catalogues.”

Eventually, though, he offers most of the items for sale. His customers are divided, roughly, into two groups—people who collect art and sculpture and see his finds as beautiful objects and people who collect medical objects.

“There are little doctor collector groups that have their own mini-museums,” he says. A cardiologist might collect old electroconvulsive therapy machines; a vascular surgeon might collect pacemakers. “I had this ocularist I was getting all these really awesome eyes from,” says Chavez. Sometimes, he’ll trade—a set of prosthetic eyeballs for a set of dental phantoms.

There’s a higher demand for certain objects; the dental phantoms and ECT machines sell quickly. Chavez himself has a particular attraction to artificial hearts, “simple crude machines that help people live.”

In the decade he’s been collecting these objects, though, some of them have become ever rarer. He used to call up a dentoform company and ask to buy older stock, but now it’s become harder to source those. Now he’s more likely to search out particular objects, researching medical forums and regional manuals for leads.

Chavez spends about half his time on his gallery work and half his time on his own art; the gallery is open by appointment only and doubles as a studio. His collection also includes gas masks for people and animals, an explosion-proof telephone, and vintage photos and drawings.

This haunting assortment is united by the same question—what is a beautiful object? The modern iterations of these same medical technologies might function better, but they’ve lost some of their intrigue as objects. “There’s something beautiful and sculptural about it, the primitive technology that’s in the middle,” Chavez says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook