The British Bake Off That’s Resurrecting a Forgotten Medieval Cake

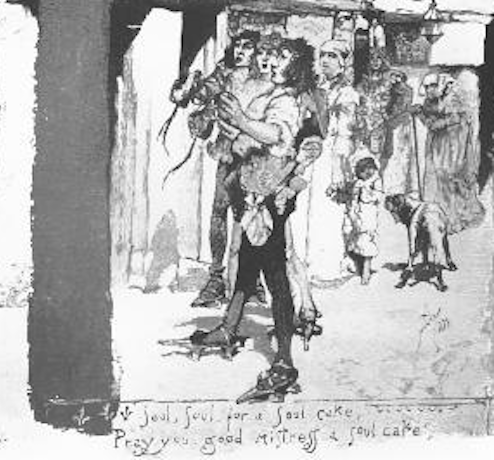

Competitors are baking soul cakes, a bygone Halloween treat.

Those of us who have seen the Great British Bake Off know that competitive baking is no joke. But in Northern England, it’s a matter of the soul. In November, a challenge from Durham University spurred bakers to whip up a soul cake, a bygone bun once integral to a medieval tradition of feeding the poor and honoring the dead. But, in the spirit of competitive baking reality shows, there was a catch: Nobody really knows how, traditionally, it was supposed to be baked.

We know generally what soul cakes looked like, and what was inside of them. We know that bakers crafted them into small, round, square, or oval buns—garnishing the top with currants in the shape of a cross. And we know its purpose: Giving a soul cake to someone in poverty allegedly freed a departed soul from Purgatory. But we’re still in the dark about its intended taste and texture, and exactly how to go about concocting a soul cake in true medieval fashion.

“We have a recipe from a household book from 1604 compiled by a certain Lady Elinor Fettiplace that includes a recipe for a soul cake,” says Dr. Barbara Ravelhofer, a professor of English literature at Durham University and facilitator of the soul cake challenge. “However, it doesn’t give us the quantities—nor does it tell us how long to bake it. So you have to work out for yourself what to do with the ingredients.” Spearheaded by Dr. Ravelhofer and the Records of Early English Drama North East team, the Great Northern Soul Cake Bake doubles as a competition and crowdsourcing project. By challenging the public to decode the bare-bones recipe, the research team hopes to understand and resurrect the original soul cake—as well as the tradition that surrounds it.

Soul cakes are connected to Britain’s early Christian celebrations known as All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, Halloween-like festivities commemorating the recently departed. On November 2nd, beggars would weave their way through the chilly darkness, rapping on wealthy homeowners’ doors in exchange for a soul cake. But obtaining it was no cake walk. To successfully soul, one had to sing for sweets.

Whether it be musical or theatrical, souling required performance in exchange for a cake—a tradition that looks a lot like modern-day trick-or-treating. And, though it’s impossible to definitively claim souling as the progenitor of tricking and treating, Dr. Ravelhofer says they’re certainly connected. However, she points out, there are key differences. “A soul-caker was somebody who did something to obtain something,” she says. “Whereas trick-or-treating strikes me as, ‘Give me something or else I’ll do something.’”

Demanding candy door-to-door, she posits, is a “slightly degenerated, commercialized form” of the All Souls’ Day transactions of medieval Europe. Souling, Dr. Ravelhofer adds, also had a strong connection to charity and memoriam. The act of doling out freshly baked goods, while thinking of a “poor, departed soul,” filled two needs with one deed, giving to the hungry and freeing a soul in question from Purgatory in one fell swoop.

While vestigial remnants of this practice can still be found in some parts of England, the tradition of souling, and the cakes that came with it, have since disappeared—until now.

To more fully understand the history and tradition of All Souls Day, Dr. Ravelhofer and her team devised the bake off. The technical challenge (the first of a series of three) called for readers to recreate a successful iteration of the festive bun using only Elinor Fettiplace’s 17th-century recipe, which reads:

“Take flower & sugar & nutmeg & cloves & mace & sweet butter & sack & a little ale barm, beat your spice & put in your butter & your sack, cold, then work it well all together & make it in little cakes & so bake them, if you will you may put in some saffron into them or fruit.”

Folks from across the globe responded, submitting recipes, photographs, and anecdotes via email, Facebook, and Twitter, with results ranging from wild successes to valiant flops.

“We had proper food archaeologists who really got into the spirit of things, and then we had candidates who tried to microwave it,” says Dr. Ravelhofer.

David Petts, Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at Durham University, posted about his soul cakes on his personal blog, likening them to “slightly dense hot-cross buns.” Another participant found that using a ruby or dark ale gave the cakes a soft, chewy texture. Yet another made a successful stoneground cake by adding rye, theorizing that medieval bakers may have used additional grains.

But cataloguing the failed cakes, Dr. Ravelhofer says, has been just as informative as admiring the more edible ones. Understanding what doesn’t work, and why, allows historians to do detective work when it comes to understanding what the recipe may or may not have looked like.

Dr. Kristi DiClemente, a professor of history at the Mississippi University for Women, created this kind of informative flop, which she’s dubbed “condemned soul cakes.”

“It was a disaster, a complete disaster,” she says of her not entirely edible creation. Dr. DiClemente, who hadn’t heard of the medieval cake before, spotted the challenge on Twitter and took it on for a fun weekend baking exercise.

“I was thinking that this was going to be like a bread, and so it would rise,” she says. She substituted a natural yeast starter for the ale barm, which she assumed to be a rising agent, and kneaded the dough. But to her surprise, what she pulled out of the oven was a far cry from the fluffy, roll-like treat she had anticipated.

“They looked like little, neat buns, and they were absolutely inedible and disgusting.” The condemned soul cakes were easy on the eyes, but apparently, quite tough on the teeth. Her theory: They’re not meant to be bread-like, but rather more the consistency of a scone or biscuit.

Dr. DiClemente hopes to try again next year. But in the meantime, she plans to bring her experience into the classroom. “When I teach my food class again, we can look at a recipe like this and say, ‘What do you think this looks like, and what does this tell us about the society that made this?’”

According to Dr. Ravelhofer, studying soul cakes—as well as the performances put on to receive them—tells us a lot about community. The plays performed to receive soul cakes, she says, were often comedies that addressed death, mortality, and other serious issues. “These plays and soul-caking are communal practices that serve community-building, but they also harness the psyche individually and collectively to come to terms with coldness, darkness, and having to die,” she says. Soul cakes, carefully spiced, sweetened, baked, and garnished, were the currency connecting the living world to the dead.

And, Dr. Ravelhofer adds, it’s also about having a good time—something that still rings true of the Halloween season. “It’s dark, it’s cold, and people want to have a little bit of fun as well!”

The other challenges involved collecting soul cake memories, and creating a new and improved soul cake recipe with added regional flair. The “most interesting” submissions will be catalogued in a booklet and distributed around Durham, and the winner will receive a dinner for two at a local restaurant. And if you know a soul in need of saving—or are just hungry for historical fare—you, too, can try your hand at baking a soul cake.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook