The Secret Meanings Behind the Beasts in a Medieval Menagerie

In Middle Age Europe, animals were popular storytellers.

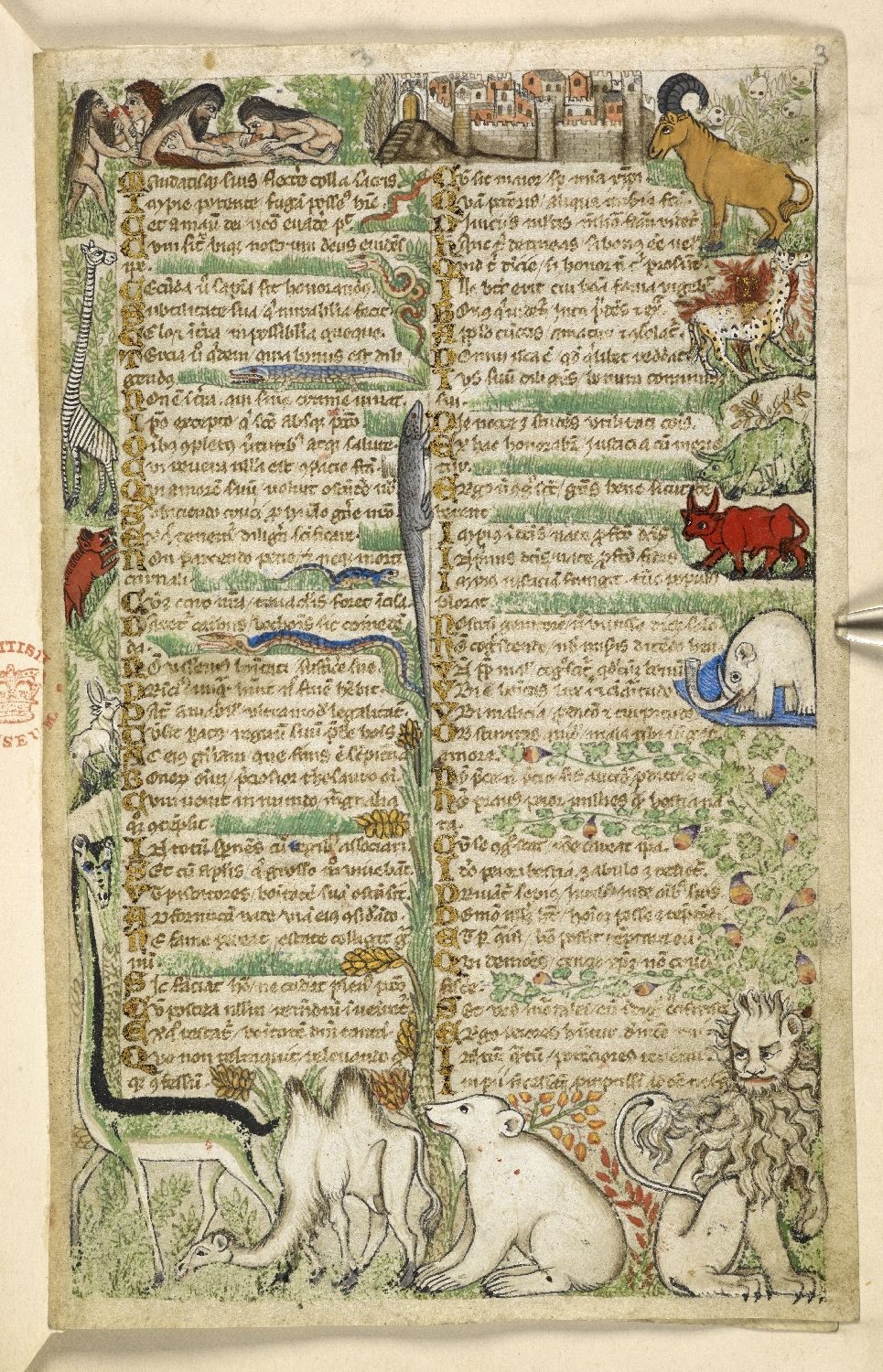

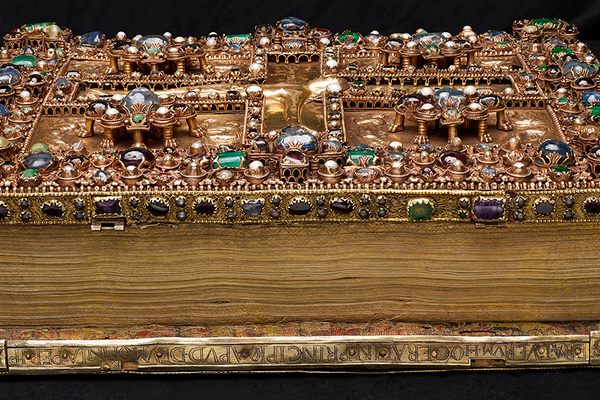

In the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, amid a vast collection of medieval texts, there is a manuscript known as The Ashmole Bestiary. It’s a particularly lavish example of one of the most popular kinds of texts in the European Middle Ages: a book of beasts, describing animals—real and imagined—and their meanings within the time’s Christian belief system.

In one of the illustrations, a fox pretends to be dead in order to attract birds; once they are close enough, it leaps to life to devour them. In another, a spotted panther attacks its only enemy—the dragon. In yet another, a lion breathes life into its dead, three-day-old cubs. These were more than mere illustrations; they were Christian allegories. According to the new edition of The Grand Medieval Bestiary—a 620-page behemoth by Christian Heck and Rémy Cordonnier, devoted to medieval creatures great and small—the fox was commonly portrayed as untrustworthy, and ensnared birds the way the devil traps sinners. The panther symbolized Christ, with the ultimate serpent—the dragon—as the devil. The life-giving lion was, of course, related to the resurrection.

The blueprint for medieval bestiaries arose long before the Middle Ages. The Greek text Physiologus, written in Alexandria sometime between the second and fourth centuries, linked particular animals to Christian morals and stories. In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville produced his 20-volume Etymologies, an encyclopedic tome on a range of subjects, from mathematics to agriculture to furnishings. Book 12 related to animals, but without the Christian moralizing. Instead, it focused on how the etymology of animals’ names related to their characteristics.

By the 12th and 13th centuries, when The Ashmole Bestiary is believed to have been written, bestiaries had become particularly popular in England. They also had broad appeal because even the illiterate could understand the stories behind the illustrations.

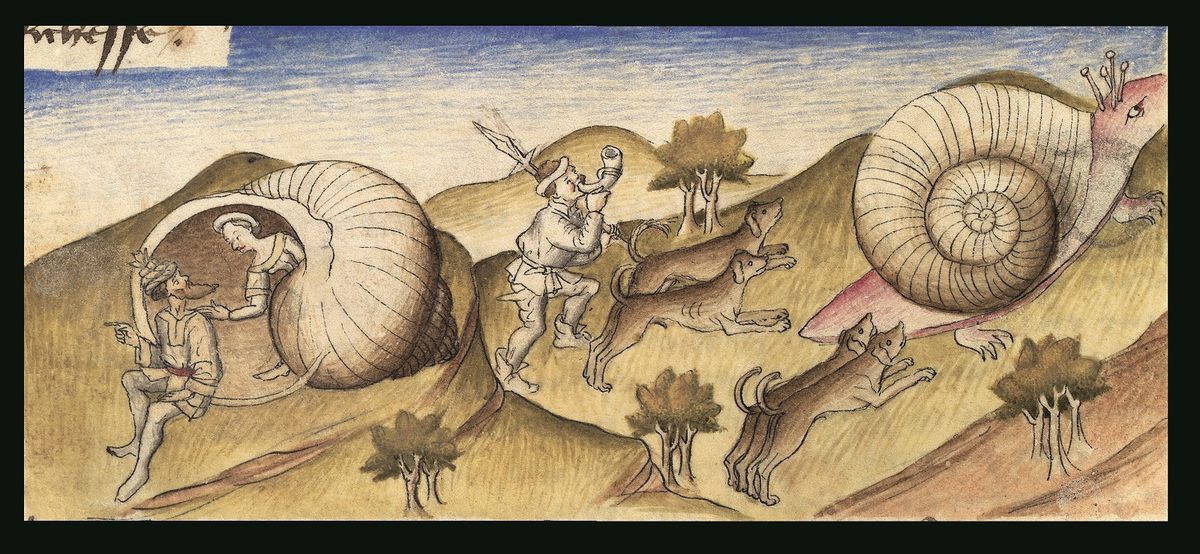

Animals appeared in medieval texts beyond bestiaries as well. Marginalia, the doodles and drawings on the edges of manuscripts of all sorts, commonly featured animals. (These drawings are not the only embellishments in medieval manuscripts, either. Some texts contain delicate embroidered patches in the parchment, itself made from animal skin.) Animals also featured in art, tapestries, heraldry, and jewelry, and continued to carry the meaning and symbolism that had long been ascribed to them.

As The Grand Medieval Bestiary points out, “Whether they are faithful servants and benevolent companions, subjects of a humorous fable or parody, wild animals that represent danger or evil, or strange creatures from afar, real or imaginary, their place on these pages is as important as the place accorded to them in the life and culture of the period.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images of medieval beasties from the compendium.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook