For Centuries, Alewives Dominated the Brewing Industry

The Church and anti-witch propaganda may have contributed to beermaking becoming a boys’ club.

Beer has been an essential aspect of human existence for at least 4,000 years—and women have always played a central role in its production. But as beer gradually moved from a cottage industry into a money-making one, women were phased out through a process of demonization and character assassination.

It’s telling that the oldest-known beer recipe comes from a Sumerian hymn to the goddess of beer, Ninkasi. It also includes a description of how the fermented beverage was made in ancient times:

[…]It is you who bake the beerbread in the big oven, and put in order the piles of hulled grain. Ninkasi, it is you who bake the beerbread in the big oven, and put in order the piles of hulled grain.

It is you who soak the malt in a jar; the waves rise, the waves fall. Ninkasi, it is you who soak the malt in a jar; the waves rise, the waves fall.

It is you who spread the cooked mash on large reed mats; coolness overcomes. Ninkasi, it is you who spread the cooked mash on large reed mats; coolness overcomes [....]

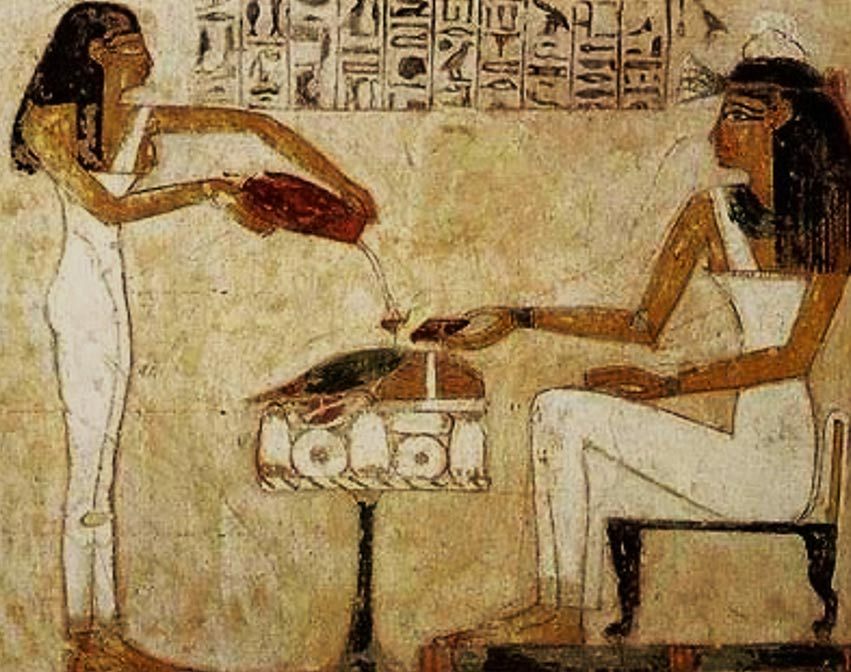

Sumerian women brewed low-alcohol beer for religious ceremonies (including ones dedicated to Ninkasi) as well as for daily food rations. Ancient Egyptians worshipped a beer goddess named Tenenet, and hieroglyphics have been found depicting women brewing and drinking beer. Baltic and Slavic mythology both include a goddess, named Raugutiene, who provided protection over beer. And the Finnish told of a legendary woman named Kalevatar who invented beer by mixing honey with bear saliva.

The image of the woman as ale-maker persisted well into the Middle Ages, moving from a sacred role to an everyday necessity of homemaking, historically typified as “women’s work.” Water in cities was unsanitary, at times bringing with it deadly diseases. But the process of fermentation created a sterile drink, so beer was considered a safer option. Most ale was very low-alcohol level, while more potent ales were reserved for special occasions such as holidays and weddings. So even before the year 1500, nearly all women in England knew how to brew.

Making beer is difficult and time-consuming in any age. But given that a typical medieval family of five might have needed roughly 9 gallons of beer to subsist per week, and said beer spoiled quickly, women had to get creative. They then began sharing the workload with friends and neighbors, a system that often involved one woman making extra each week to sell to other households. As this culture of shared work evolved, some women in England began making ale more professionally, with some providing a constant flow of it for sale. Occasionally, these women might open makeshift bars located in their own homes, where people could sit together and drink. And so the term “alewife” (or “brewster”) emerged, referring to a woman who brewed beer for a small profit.

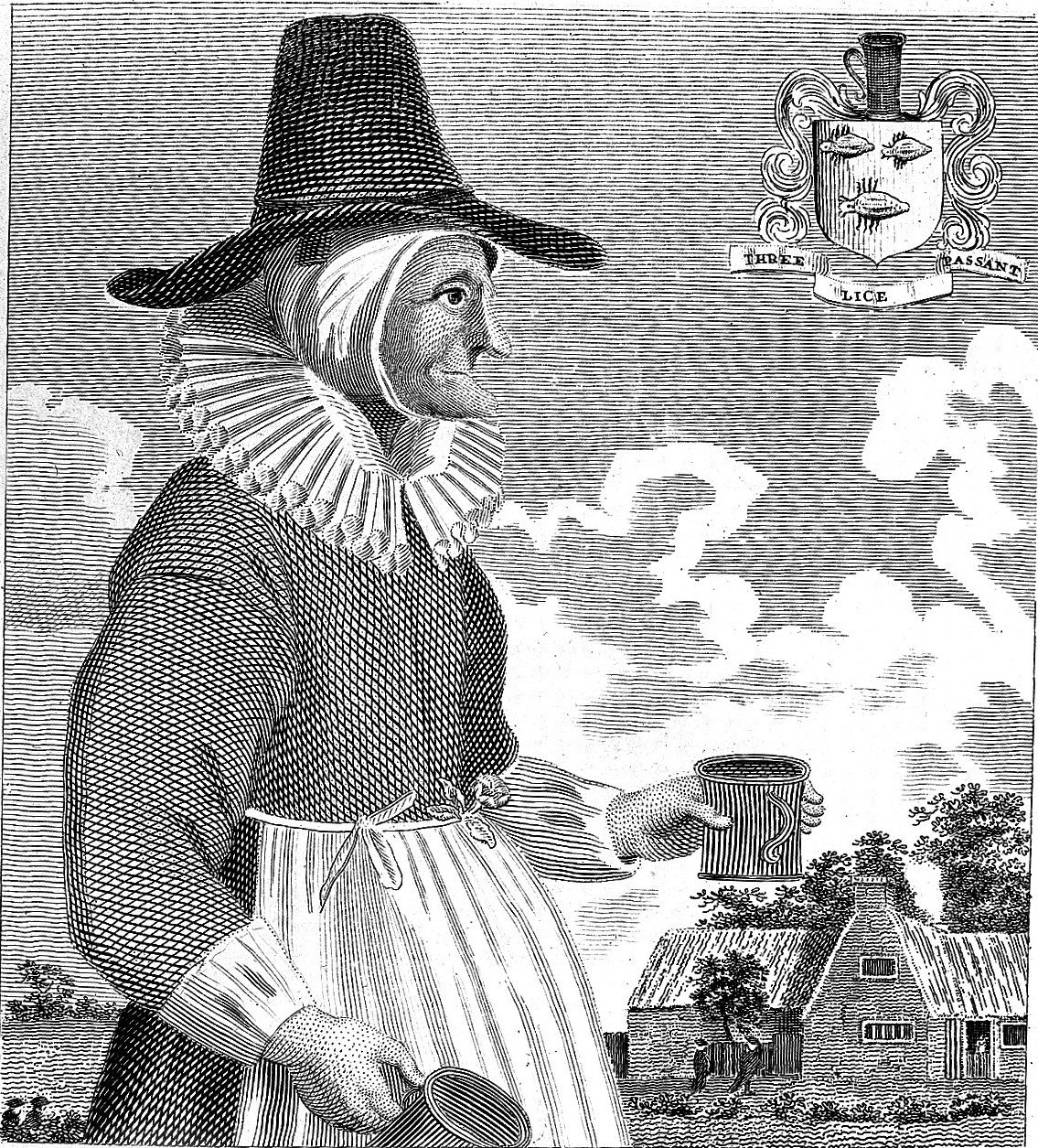

Professional brewsters and alewives had several means of identifying themselves and promoting their businesses. They wore tall hats to stand out on crowded streets. To signify that their homes or taverns sold ale, they would place broomsticks—a symbol of domestic trade—outside of the door. Cats often scurried around the brewsters’ bubbling cauldrons, killing the mice that liked to feast on the grains used for ale.

If all of this sounds familiar, it’s because this is all iconography that we now associate with witches. While there’s no definitive historical proof that modern depictions of witches were modeled after alewives, some historians see uncanny similarities between brewsters and anti-witch propaganda. One such example exists in a 17th-century woodcut of a popular alewife, Mother Louise, who was well-known in her time for making excellent beer.

While the relationship between alewives and witch imagery has still yet to be proven, we do know for sure that alewives and brewsters had a bad reputation from the jump. Beyond the cheating that some of their counterparts engaged in, brewsters also had to deal with the bad rap their entire gender suffered because of original sin. “The ale trade was (and is) filled with trickery—poor ale substituted for good, pint measures that were just a bit too small, inflated prices, and of course, inebriated customers who found they’d been robbed or cheated,” explains Dr. Judith Bennet, author of Ale, Brewsters, and Beer in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World 1300-1600. “For medieval people, it was easy to link these deceptions with women. Were not women, as daughters of Eve, naturally more deceptive and wicked than men? By such logic, any alewife, no matter how friendly and open, was suspected of being a secret swindler.”

The medieval Church was also not a fan of brewsters. They saw these early female entrepreneurs as temptresses who used their wiles to get pious men drunk and spend money. The Church also saw alehouses as playgrounds for the devil, where the cardinal sins of gluttony and lust ruled supreme.

Furthermore, as Bennet notes, one of the most iconic images of feminine evil in the Middle Ages was that of the alewife in hell: The Church specifically taught that alewives would be the only people left in hell after Christ freed all the damned. “Enacted in plays, drawn on the walls of parish churches, and carved into wood, it was a fate that medieval people imagined with resentful glee,” Bennet details.

Brewsters’ bad reputation didn’t help their case when wealthier, more socially-connected men started taking up the trade. After the devastation of the Black Plague, people began drinking a lot more ale, doing so in public alehouses instead of at home. This also marked a shift in people’s relationship with beer, which moved from being just a necessity and occasional indulgence to something closer to what we have today. Men suddenly saw they could make a real profit off of what was once seen as a semi-lucrative side gig for women. So they built taverns that were bigger and cleaner than the makeshift ones that alewives provided, and people flocked to them to revel and conduct business alike. Over time, alewives grew to be seen not only as tricky, but also dirty and their beer unsanitary.

Women continued to make low-alcohol ale for their family’s daily consumption after the Industrial Revolution increased production methods, which made buying beer cheaper and easier than making it at home. But that died in the 1950s and 1960s, when marketing campaigns branded beer as a “manly drink.” Companies such as Schlitz, Heineken, and Budweiser depicted beer as a means of unwinding after a long day of work, often featuring women serving their suited-up husbands cold bottles of brew.

That’s been a factor in why the contemporary brewing industry is a notorious boy’s club, but the craft beer industry has helped moved the needle a bit: A 2014 Auburn University study found that women represented 29% of all brewery workers. It seems that the brewing industry has taken a circuitous route, moving away from small homebrewing methods to large-scale production, and back again. These days, the sky’s the limit for brewsters. They don’t even have to ride broomsticks to get there.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook