Found: An Early Merlin Tale, Hidden for Centuries

The fragments tell a new version of the magician’s encounter with the enchantress Viviane.

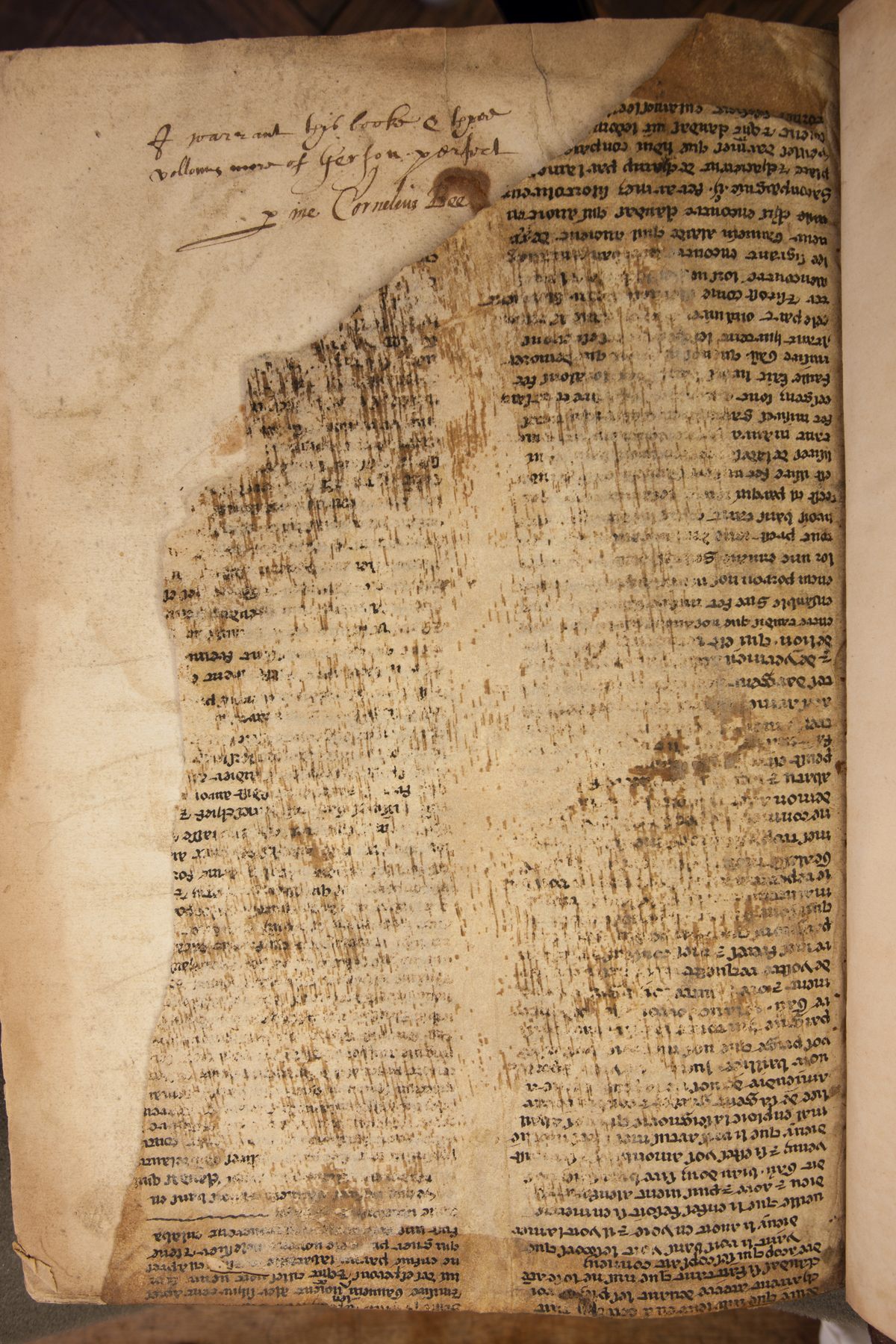

Michael Richardson, special collections librarian at the University of Bristol, wasn’t surprised to find forgotten parchment scraps from medieval manuscripts hidden inside some of the books at Bristol’s public library. The library, established in 1613, is one of the oldest in England and has an antiquarian books collection that rivals any university’s. And where there are old, rare books, there are often older, sometimes rarer parchment fragments recycled into those books’ bindings.

But Richardson didn’t expect to stumble on several medieval fragments written in Old French glued into the binding of a late 15th-century tome. That was odd because most fragments are liturgical texts written in Latin. In total, Richardson found seven fragments of various sizes in the book. And when he looked closer at the dark lampblack ink scratched onto the parchment, he was able to make out two familiar names: “Merlin” and “Arthur.”

Now, two years after Richardson’s unexpected discovery, scholars have determined these fragments are evidence of one of the oldest known Arthurian manuscripts of its kind. In their new book, The Bristol Merlin: Revealing the Secrets of a Medieval Fragment, medieval literature scholars Leah Tether, Benjamin Pohl, and Laura Campbell also reveal that the fragments spin a different tale from the version of events scholars already knew.

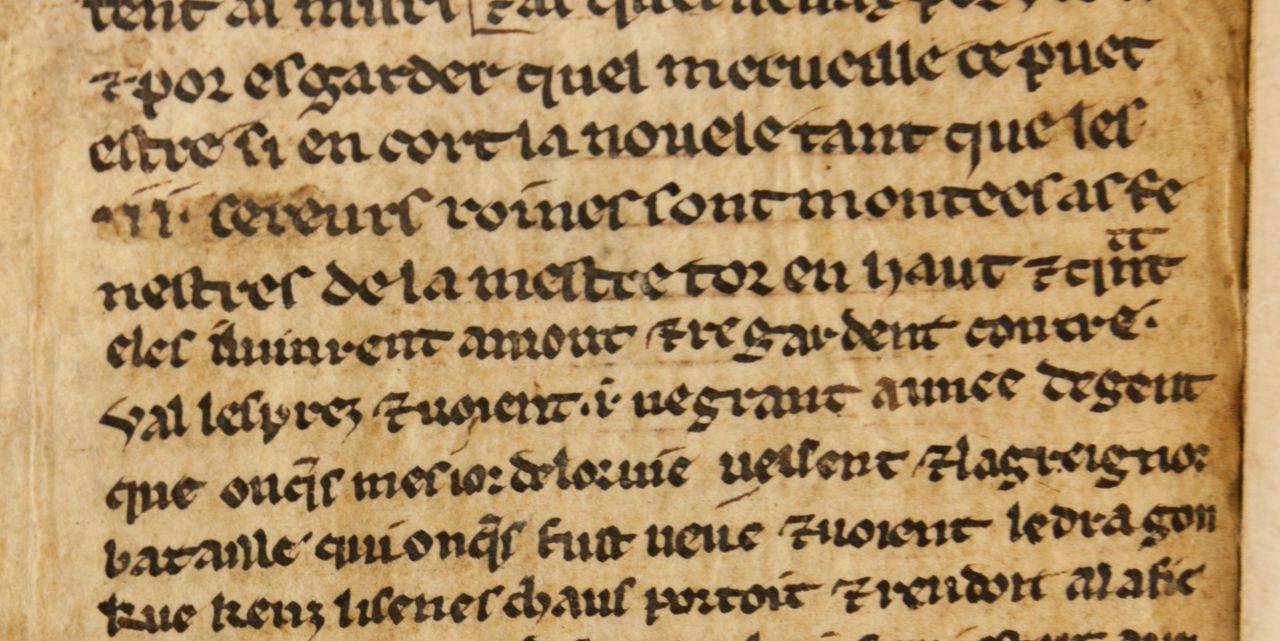

The Old French fragments Richardson found in 2019 are part of a medieval King Arthur story known as the Vulgate Cycle or Lancelot-Grail Cycle. The original text of the Vulgate Cycle was written sometime around 1220. By analyzing the letterforms and vernacular language of the Bristol find, scholars were able to date the folio pieces to a manuscript written sometime between 1250 and 1275, likely in northern or northeastern France.

The uncovered partial and full manuscript pages contain some key differences from other versions of the Vulgate Cycle, particularly when it comes to Arthur’s wily magician friend Merlin. “The most significant difference to be found in this particular set of fragments is where Viviane, the enchantress, casts a spell,” says Leah Tether, a Bristol Merlin co-author. In the known version of the story, Viviane’s spell tattoos three names onto her groin, preventing Merlin from sleeping with her. In the newly unearthed version of the story, Viviane’s spell engraves three names onto a ring, which prevents men from speaking to her. This, says Tether, is the “most chaste version” of Merlin’s encounter with the sorceress.

All 200 known versions of the Vulgate Cycle have some variations and scholars are still unsure which is closest to the original tale. In the Middle Ages, bookshops relied on hired scribes to copy manuscripts based on “exemplars,” texts written to be transcribed. “With medieval texts there was no such thing as copyright,” says book co-author Laura Campbell. “So, if you were a scribe copying a manuscript, there was nothing to stop you from just changing things a bit.” These changes could’ve been accidental or purposeful, says Campbell. The patron in this case may have wanted something a little less raunchy.

Researchers have also learned that only 80 or so years after its creation, the manuscript journeyed from France to England. “We know it was in England by that point [because] someone has written ‘my god’ in the margins in English,” says Campbell. “From the handwriting, we’ve dated that to the early 14th century.” Campbell says the annotation might have been “handwriting practice” or someone seeing if their quill was properly sharpened.

Sometime prior to 1520, the manuscript ended up in yet another bookshop, likely in Oxford or Cambridge. This time it was “in a pile of scrap,” says Campbell. There, the manuscript’s parchment was bound into a book on French philosophy. That book ended up at the Bristol public library where the Vulgate Cycle fragments sat until Richardson’s visit.

The Bristol fragments offer yet another perspective on Merlin, who has taken on many different guises through the centuries. In some of the earliest Merlin stories, he’s this “creepy little boy [whose] father is a devil,” says Campbell, or a “morally dubious” seer who likes to live in the woods. But in modern retellings, he’s Arthur’s wise, grey-haired advisor. Versions of him can be found in Lord of the Rings’ Gandalf or Dumbledore from the Harry Potter series. Every Merlin, though, seems to know more than is good for him which often “necessitates getting rid of him,” Campbell says. Perhaps that is his lot—to reveal a truth only before disappearing again. With each new discovery, Merlin, like any true magician, continues to shapeshift his way through history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook