To Imagine a 39-Million-Year-Old Forest, Start Small—Very Small

Decades of work has revealed a “megadiverse” ancient landscape in northern Peru that was destroyed in a volcanic eruption.

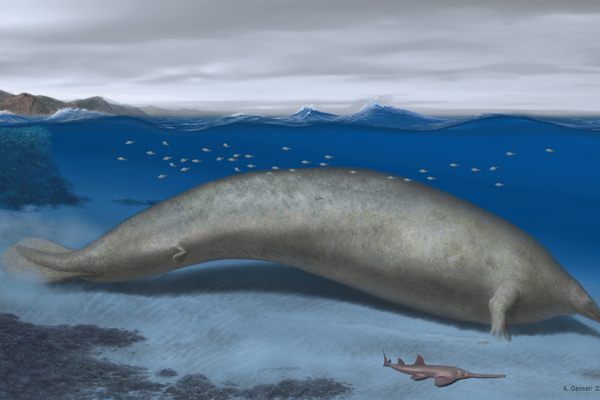

Before it was lost, it must have been a wild paradise: a lowland tropical forest near the sea and thick with tall palms and other slim, flowering trees. Woody vines snaked through the dense understory, shaded by relatives of today’s cashew and tropical chestnut trees, while stout hop-bushes clustered where sunlight pierced the canopy. Black mangroves sank their roots into the water where crocodiles likely waited, silent and patient, for an unsuspecting meal to wander past. The air would have been thick with birdsong and the click and buzz of insects. Then everything changed.

The sky darkened and choking black ash rained down. Rivers of hot ash snapped trees in half or uprooted them, and then dumped them in a mass grave. A volcanic eruption in what’s now northern Peru destroyed this tropical forest 39 million years ago, but the story does not end there.

Fragments of the forest, buried in ash, were fossilized. The Andes continued to rise, a fitful process across millions of years that pushed the remains of that lowland forest site skyward. At last, at more than 8,000 feet above sea level, the rocks surrounding the petrified forest began to erode, revealing the world hidden within. After more than 20 years of work, a team of researchers has been able to reconstruct what that world was like, but it wasn’t easy.

“You have to have a taste for this, looking and looking through the specimens,” says project coleader and Clark University research scientist Deborah Woodcock, who specializes in paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Woodcock and her colleagues first had to understand the geological forces that created the petrified forest of Piedra Chamana, located near the small village of Sexi in Peru’s northwest corner. That meant dating the rocks and piecing together the chain of events that followed the eruption.

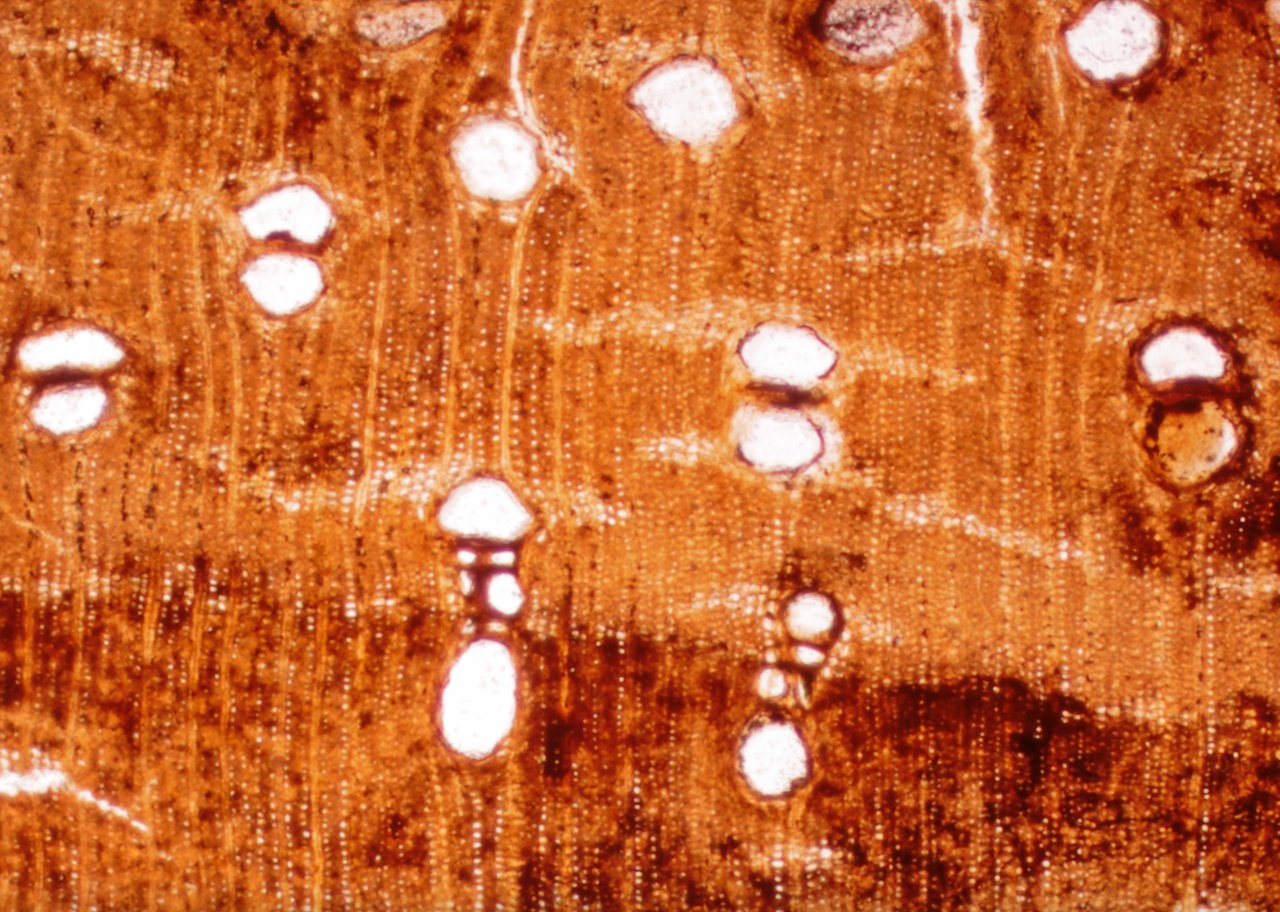

Then there was sorting through samples of the trees themselves. The ashflows provided a quick burial, allowing much of the material to be preserved in stunning detail, even on a cellular level. Woodcock says one of the biggest challenges of the project was figuring out how to sample the huge diversity and volume of fossil material collected from the field. The team prepared thin slices of different fossils and then, using light microscopy, compared them to other samples in extensive databases. The fossil sample shown at top, for example, belongs to Cynometra, a genus also found throughout the tropics today. As the team identified more of the trees from the ancient site, they were able to recreate much of the ancient “megadiverse” forest. Now their findings appear in several papers, including one published in 2020 in the Annals of Botany.

One thing not found at Piedra Chamana, at least so far: fauna. While animal remains may have been washed away or simply destroyed in the violent eruption’s aftermath, Woodcock says one portion of the site, not yet excavated, includes trees still standing upright and rooted in ancient soil. The location has potential for future finds of insects and other soil-dwellers, and, she says, “maybe something bigger and more interesting.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook