These Colorful Piñatas Bring Medieval Monsters to Life

Roberto Benavidez makes eye-catching art inspired by centuries-old paintings and illuminated manuscripts.

You aren’t going to want to take a bat to Roberto Benavidez’s piñatas, and he’ll never tell you what’s inside of them.

His paper-fringed sculptures, some of which will be on display in February 2019 at the Riverside Art Museum in Riverside, California, take months to finish and are inspired by animals in medieval imagery.

Benavidez’s original inspiration for his medieval piñata project came from The Garden of Earthly Delights, a modern name given to a Hieronymus Bosch oil painting containing a phantasmagoria of naked people and mythical animals. When Benavidez first saw the painting, he was drawn to the strange creatures. He wanted to bring the flat images to life.

“I could spend probably my whole life making everything I would like to from that painting. There’s so much detail,” he says. Benavidez’s beasts are at once ominous and friendly, hearkening to something old while simultaneously feeling fresh and new.

This mix can partly be attributed to his medium, rarely seen in the world of fine arts. “When I decided to pursue the piñata technique it really was to pursue a medium that was limitless to me,” says Benavidez. “There was no financial limitation. It’s just like glue and paper. You can really make anything with paper.”

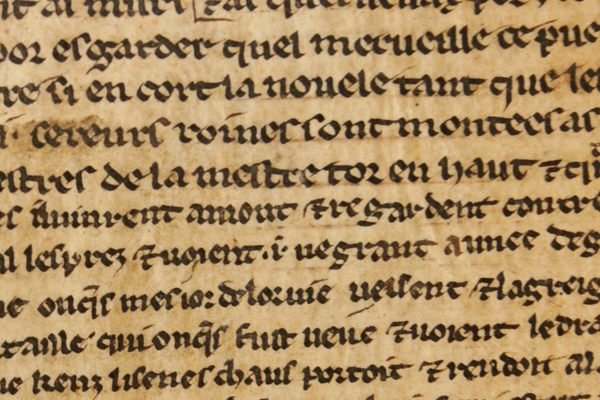

Benavidez’s approach combines traditional piñata elements and motifs to create his own kind of hybrids. His latest project, “Illuminated Piñata,” pulls animal characters from the Luttrel Psalter, a richly painted 14th-century manuscript full of strange beings.

Piñata-makers often struggle with copyright privileges, notes Benavidez, so working with 500-year-old texts helps him draw on inspiration without getting sued. “There are so many images out there you can use that are interesting,” he says. “Why not expand beyond these images that are protected by intellectual property and go a little further back and celebrate what’s been done in the past?”

Like most medieval art, the texts that inspire Benavidez’s work have religious themes, and piñatas also have a religious history in North America. Some believe Spanish missionaries used piñatas to convert indigenous people to Christianity. “I kind of like that there is that slight parallel,” says Benavidez, “but that’s not what drove it.” For him, it was all about the creatures, and their “soft and hard qualities.”

Benavidez says he has received some pushback against the piñatas, and some of his friends have asked him why he won’t just call them “paper sculptures” instead. “There was incredible resistance to just the word ‘piñata’ being used in a higher art form,” he says. “I love presenting them as piñatas because I love the tension that it brings.”

Growing up in South Texas, Benavidez saw many piñatas at parties. He likes to think that he is highlighting an art form that hasn’t been highlighted before in this way. He identifies as mixed-race, a fusion of histories and cultures, and he thinks his piñatas are the same way. “The piñata’s history is very multicultural,” he says. “In my mind, it’s a reflection of me.”

The largest of his pieces are over six feet tall. Thousands of paper strips are hand-cut and layered to achieve the different hues and textures. He used to make the piñatas in the traditional way, with wheat paste and newspaper, but he has since shifted to more durable acid-free papers.

Most of the pieces are designed to hang from the ceiling, and Benavidez has to place the ring in the exact right spot early in the construction process to achieve the right equilibrium.

In Benavidez’s work, these creatures balance between the curious world of medieval animal imagery and the exuberance of a South Texas birthday party, between tradition and something completely new. “I just want to spark people’s’ imagination of what’s possible,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook