Meet the Pioneering Midwives Who Helped Birth the Gulf South

Marie Grissot and Aimée Potens are just two of the women finally being written back into the history of childbirth.

A statue of Dr. J. Marion Sims, known as the “father of gynecology,” stands in front of the Alabama State House in Montgomery. In fall 2021, another set of statues went up in Montgomery, in honor of his victims: Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey, three enslaved Black women that Sims conducted brutal experiments on in order to develop new techniques in obstetrics.

Men like Sims, for centuries, have gotten most of the credit in the history of gynecology. Far less noted are the women whose skills were essential to the birth of new communities—like Marie Grissot, who fought to save the lives of babies and mothers as the sole midwife in colonial Louisiana, and Aimée Potens, a free woman of color who earned a place of pride and privilege for herself as a midwife before and after the Civil War. “These women were not secondary figures in history,” says Mark Roudané, Potens’ great-great-great grandson.

Today, Louisiana has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the U.S., and the death rate is twice as high for Black mothers compared to White. At the same time, the region has not made it easy for midwives to work, despite research suggesting that birth outcomes are better in states that encourage midwifery. Alabama is considered the second-worst state in the U.S. for midwives to practice in, and Louisiana the 14th-worst. The stories of Grissot and Potens are vital parts of history—and a testament to the contributions of midwives in a region where there’s still a critical need for investment in maternal health.

Marie Grissot, a widow, arrived in 1704 at the fledgling colonial capital of Mobile, in present-day Alabama, in the same boat as 24 young women who were shipped across the ocean to marry settlers. As the sole midwife in the entire Louisiana colony, which went from a little over 300 people in 1708 to around 5,000 in 1721, Grissot was paid a royal salary and enjoyed rights given to no other women. As an essay by historian Molly Reid Cleaver describes, her job allowed her to travel at all hours, enter any home, and even perform baptisms.

Her job was also often heartbreaking. Famine, flooding, and fever were constant threats in the colony. Years passed without supply ships from France. Each birth was a life-or-death struggle, and at least three infants died in the winter of 1705, although Grissot was not blamed for these losses.

Yet despite these desperate conditions, the colonial commandant—Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville—decided that the midwife was a pointless expenditure. Bienville was annoyed when Grissot refused to attend sick soldiers, complaining that there was no hospital in the colony and no one to care for the sick besides a soldier assigned to the task. Grissot, however, argued that she didn’t want to spread infections to vulnerable mothers and infants. The colonial ruler sliced Grissot’s salary in half and gave the money to her brother-in-law, a “much more useful” carpenter.

“I believed it worthless to have a salary given to a person for no service at all,” Beinville wrote in a 1711 letter to royal authorities.

Grissot’s poor treatment reveals a bias against midwives that persists in the South to this day, says Kate Paxton, founder of Lantern Midwifery in Arizona. Paxton, who helped create an exhibit on the history of obstetrics and midwifery for the Pharmacy Museum of New Orleans, worked for years as a midwife in Louisiana. She ended up moving due to her frustration at local laws that forced her to practice with “clipped wings.”

“The entire Southeast, midwives do not have full practice authority and they have been fighting for it for a long time,” she says.

The challenges Grissot faced, Paxton feels, still resonate in her profession today.

“There’s a stated goal of caring about moms and babies, but not necessarily the finances and the support that would actually help support moms and babies—whether that’s Marie Grissot fighting for her salary or supporting women by having adequate resources for food and nutrition,” says Paxton.

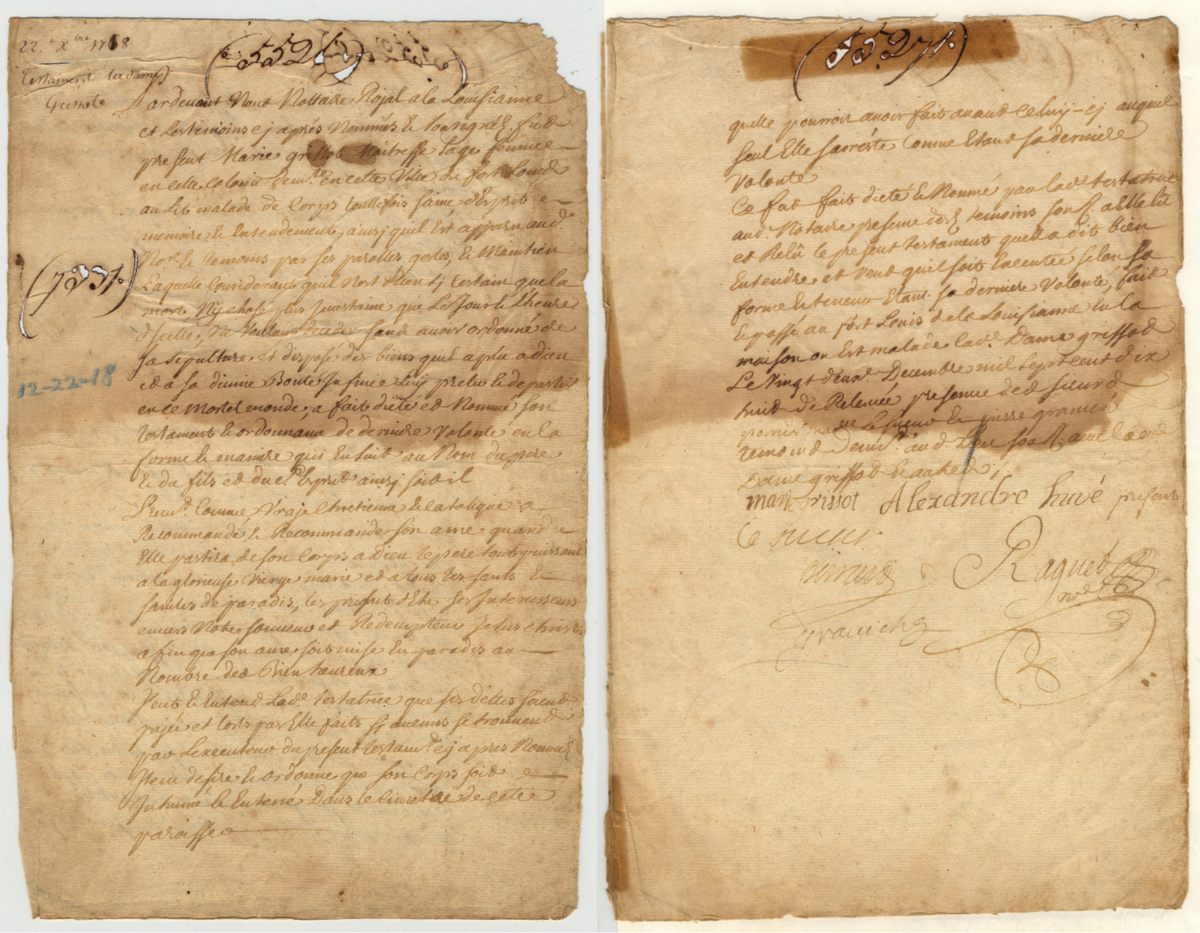

It took five years for Grissot to regain her salary. When she died in 1718, she got her revenge on her brother-in-law by cutting him out of her will. He got his revenge by cutting her out of history: the book he wrote on his travels in the colonies doesn’t mention her at all.

Nearly 100 years later, another woman in the Gulf South found a way to find rare agency and power through her role as a midwife. Rose-Aimée Potens was born in New Orleans in 1792, at a time when Spain ruled the colony. Under Spanish law, enslaved people could buy their freedom, and so Potens’ mother Charlotte-Brion was able to free herself in 1794. It then took her 17 years to scrape together the money to purchase and free her two daughters.

Once free, Potens carved a place for herself as a midwife, one of the few roles where Black women could control their own destiny. Serving both white and Black women on the enormous plantation of Marius Pons Bringier, Potens earned both money and esteem; even slave owners had to admit that she deserved respect.

“In herself was centered two claims on the family for gallant services, and she was quite conscious of the fact, for she rather regarded herself as a sort of privileged personage,” recalled Bringier’s great-granddaughter, Louise-Olivia Tureaud, in an interview circa 1910. “My mother told me she was a tall mulatress, always dressed in black, with a tignon, erect and very stately in her bearing.”

Through her work, Potens built a life for her children that her enslaved mother could only have dreamed of. She found a way to send her son Louis Charles Roudanez to Paris to study medicine. After manning the barricades during the French Revolution of 1848, Roudanez got a second medical degree at Dartmouth, writing his dissertation on obstetrics. He and his brother Jean Baptiste went on to found the New Orleans Tribune, America’s first Black daily paper.

“Aimée’s agency and power as a person of some importance was not achieved easily,” says Roudané, Potens’ descendent. “It was something she had to fight for.”

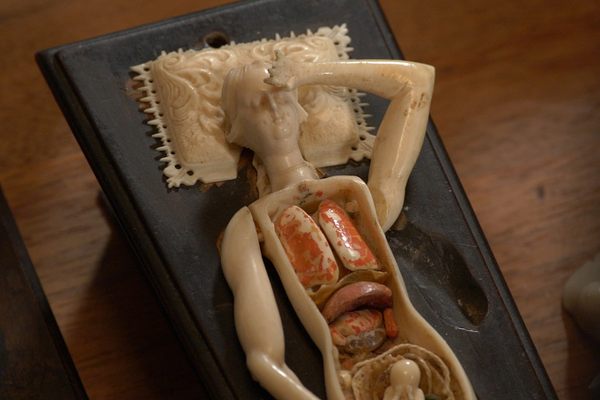

Yet as much as Potens’ work empowered her, it came at a time when a more medicalized, more male-centered model of birth was starting to compete with midwifery—a model that also had no qualms about using Black women in medical experiments. During the era when doctors like Sims were using Black women as their guinea pigs, Potens’ work at least allowed enslaved mothers to give birth in the presence of someone who gave them space for their humanity.

It was a paradoxical time for Black mothers. Their lives were quite literally valued less than white lives; for example, a Louisiana doctor in 1824 charged $30 for white births, but only $15 for Black ones. At the same time, when the U.S. banned the importation of slaves in 1808, the ability of Black women to procreate became all-important to slaveowners. As an economic investment, childbearing Black women were highly valuable; as human beings, they were worth almost nothing.

Black women were, therefore, the ideal, unwilling subjects for medical experimentation in obstetrics. Home to a number of French-trained surgeons, Louisiana became a hotspot for Cesarean sections, an often-fatal procedure first successfully performed in the U.S. in 1794. According to the Pharmacy Museum, around one-fourth of all C-sections in the U.S. from 1822 to 1877 were performed in Louisiana, all on enslaved women.

To this day, Black women are disproportionately likely to get Cesareans. And until last year, the medical algorithm for determining whether it is safe for a woman to have a vaginal birth used race as a variable, a move that critics said pushed Black women into unnecessary C-sections.

As Potens died in 1878, midwifery was losing ground to the male-dominated obstetrics profession. Sims, whenever any of his patients died, blamed it on “the sloth and ignorance of their mothers and the Black midwives who attended them.” There were around 300 registered midwives in New Orleans in 1917; a century later, there were about 15.

Statues of men like Sims are going down, but the history books remain largely silent on the women who changed history in their own ways. Grissot and Potens both found a way, in midwifery, to navigate the complexities and restrictions of their eras. In doing so, they became the true mothers of Louisiana and Alabama.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook