For Centuries, Know-It-Alls Carried Beautiful Miniature Almanacs Wherever They Went

The small, ornate tomes were big status symbols.

Several thousand years ago, in Babylonia, someone chiseled columns of text onto a tablet that set down instructions for what people might expect on any given day of the year. Some boded well—the first day of the new year was “completely favorable,” with good luck at every turn—while others called for caution. Twelve days in, it was dicey to barter grain, two days after that was prime time to bring up legal woes, and three days later, according to the inscription, doctors should dodge their patients. Consulting each day’s forecast could be difficult if you were out and about—but eventually, people found a way to take their information and prognostications with them wherever they went.

The Babylonian Almanac is among the earliest texts to lay out such daily prescriptions and predictions. From there, the format took off. By the early modern era, Europeans were eager to know how to carpe the heck out of each diem, and when to evade danger by laying low. In the pages of almanacs, readers found calendars and counsel—everything from reminders about religious feast days to details of the lunar cycle, according to Cambridge historian Lauren Kassell. Readers snapped up these volumes in huge numbers. During the Renaissance, historian Bernard Capp has noted, English almanacs sold some 400,000 copies a year—bested only, perhaps, by the Bible.

Each almanac had a shelf life, though—precisely 365 days. By and large, Kassell has written, they were ephemeral, “discarded in December, used to light a fire or tossed down the privy.” Each January, you’d grab a fresh edition for a new set of forecasts and factoids and everything you needed to know for the months ahead.

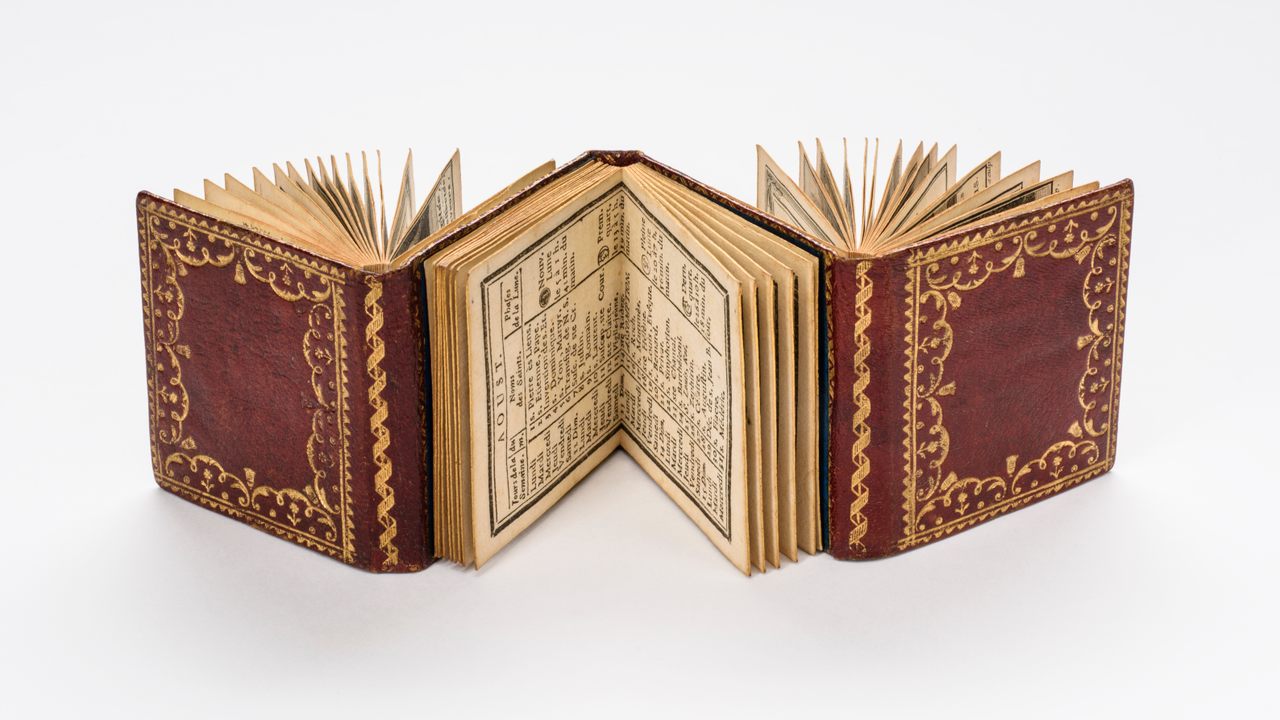

Despite this, some of these volumes were made with striking craftsmanship and dazzling details. An untold number were deliciously, ostentatiously, really, really small—made for people with nimble fingers, impeccable eyesight, and deep pockets.

Almanacs of any size had the appeal of putting information right at your fingertips, and the smaller versions—some as tiny as a postage stamp—added the allure of ultimate portability. It’s hard to say exactly when miniature almanacs emerged, but a bibliography of miniature books compiled by former Newberry cataloger Doris Varner Welsh lists a calendar for the year 1475, made in Trent, as an early example. (That one held six leaves and measured roughly three inches by two inches.) Suzanne Karr Schmidt, curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Newberry Library in Chicago, describes these volumes as “showpieces.” Miniature versions with virtuosic details, such as embroidered or painted bindings, “were really meant to be these little jewels of the format,” Schmidt says. They demonstrated care and skill on the part of the printer, who may have had to enlist new tools and smaller type for the format.

The palm-sized guides would also have slaked the period’s thirst for novelty accessories—particularly practical ones. Readers commonly yoked books to their bodies with girdles, and by the 18th century, wealthy women toted little nécessaires stocked with thimbles, thread, and other sewing supplies. An almanac was a go-to tool, and a miniature version, Schmidt says, would have signaled “the cachet of having a different format.” Small and striking as they were, Schmidt says, they really would have gotten some use.

Collector Patricia J. Pistner only has eyes for the little guys—she exclusively looks for small books, ranging from the macro-miniature (smaller than four inches in any dimension) to the ultra-micro-miniature (which can’t exceed 1/4 of an inch in any direction). Some 950 of her tiny treasures are on view at the Grolier Club in New York through May 18, 2019—with several miniature almanacs among them.

“I’m particularly fond of little French almanacs,” Pistner says. “I’ve been collecting these for about 34 years.” These volumes sparked Pistner’s love affair with tiniest tomes when she had set out to stock the library of her miniature, 18th-century French model townhouse. Pistner estimated that the shelves would hold between 500 and 600 of them—but over three decades, she’s only found 95 or so. She continues to comb rare book fairs and work with dealers to find more.

The fact that almanacs were designed to be discarded makes it difficult to estimate how many miniature versions were produced, but “apparently, more of these [almanacs] were printed and attractively bound than any other kind of miniature book,” writes Jan Storm van Leeuwen, an instructor at the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School and co-curator of the Grolier Club exhibition, in the accompanying catalog. The pages of almanacs of all sizes brimmed with weather forecasts, timetables for coach routes, tide charts, and “tables for converting money, weights, and distances,” Storm van Leeuwen writes. Buyers of fancy miniature versions could select which sections they wanted to have bound, which meant that many almanacs printed in the same place in the same year could contain different information. In some cases the bindings were designed so that the almanac pages could be replaced each year, and the precious exteriors reused.

Pistner’s collection includes several stunners, including a 15th-century German example with bold astrology and astronomy charts, and some 19th-century versions from London and Paris that probably would have been given as gifts. An 1805 edition from London’s Company of Stationers bears the sign of an ouroboros—a snake eating its own tail, symbolizing the infinite—encircling a pair of initials, and an 1818 Parisian version was designed to be worn as a locket, with mother-of-pearl covers engraved with a pair of roses. Many feature painstaking embroidery, such as a long, rectangular hunting almanac produced in Liège, Belgium, in 1745. The cover depicts a rolling green landscape with sparse blue clouds and a spindly tree, where a hunter and two dogs leap at a wolf. Above them a banner reads, somewhat ominously, “LA FIDELITE NOUS DETRUIS” (“loyalty destroys us”).

We still carry versions of handheld almanacs today, of course, one that chimes with notifications about the weather and news. They can tell us nearly anything we want to know, and though they don’t last forever, they usually stick around for more than a year, at least. Smartphones are equally as portable, too—but it’s hard to argue that they’re even half as lovely.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook