How Medieval Chefs Tackled Meat-Free Days

Dolphin sausages somehow qualified.

A riddle: When is a puffin not a puffin?

The answer: When it’s a fish.

The same applies for beavers’ tails, barnacle geese and tiny baby rabbits. All definitely, definitely fish. That is, if you’re a Medieval chef in Western Europe, and it’s a fast day, and you’re gearing up for yet another meal of almonds and salted cod.

Christians observed at least three fast days a week for much of the Middle Ages, usually on Wednesday, the day Judas betrayed Christ; Friday, in penance for His suffering; and Saturday, to commemorate the Virgin Mary. In addition to that, there were other periods of fasting throughout the year, the longest of which was the 40 days of Lent. Fasting was a form of self-discipline, writes Bridget Ann Henisch in Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society: “a spring-cleaning to freshen the soul and make it ready to receive God’s grace.”

From the outside, the rules seemed clear: On these days, no animal products (eggs, dairy, meat) could be eaten, though anything from the water was another kettle of fish altogether. While pigs, cows, sheep and other land-beasts had had to shelter from the Flood on Noah’s ark, fish were exempt, and therefore permissible.

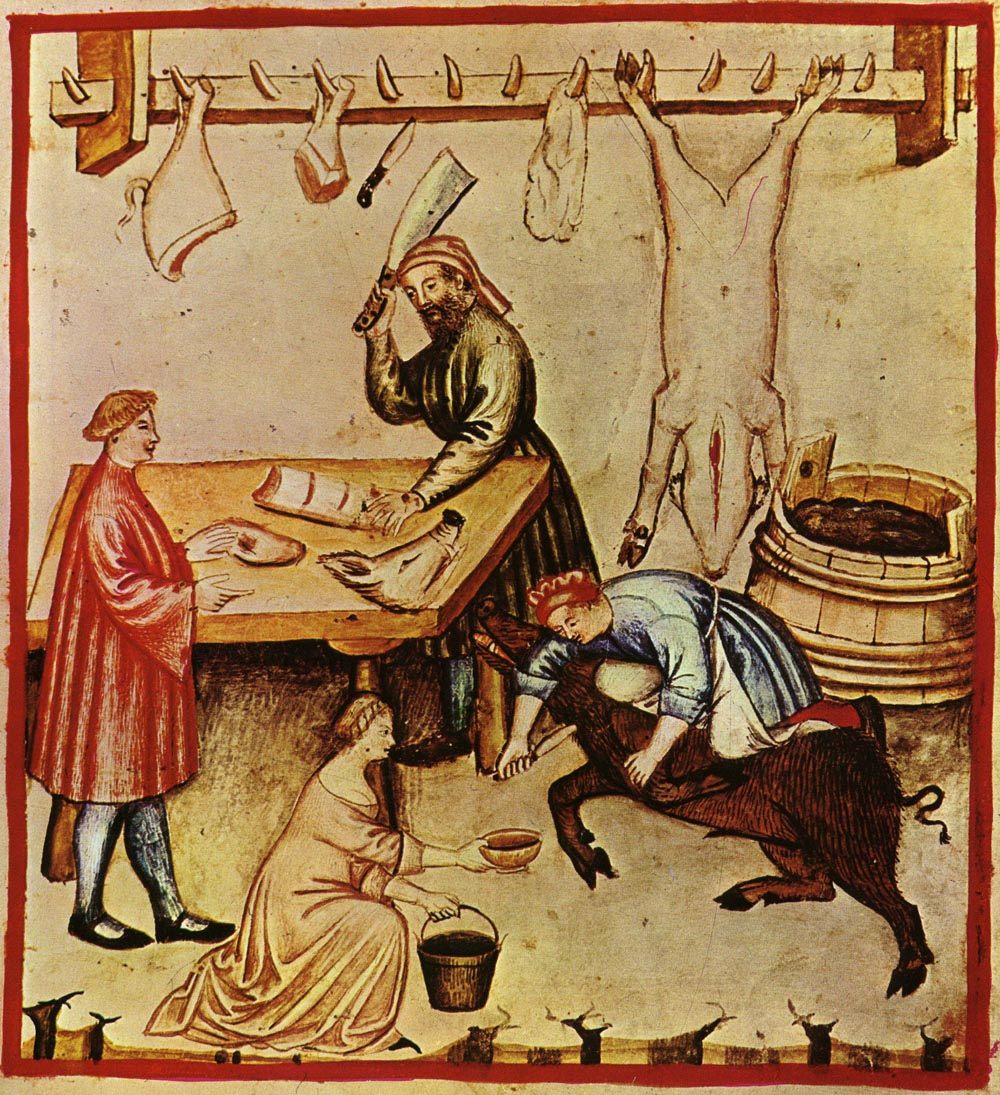

A fast day didn’t necessarily indicate eating less, or even less expensively: the only real change to the menu was the substitution of fish for meat.

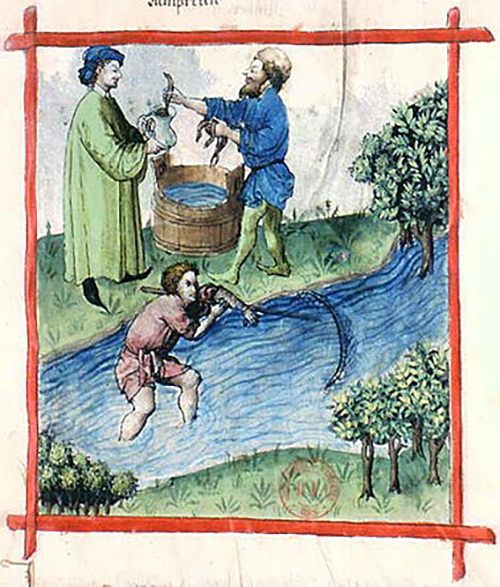

Coastal folk had it relatively easy, guzzling down seafood, but for those living inland, the abstinence was on an entirely different scale—weeks upon weeks of muddy-tasting freshwater fish or salted herring and cod.

For many, this quickly became a struggle. One 15th-century schoolboy noted in his personal book: “Thou will not believe how weary I am of fish, and how much I desire that flesh were come in again. For I have eat none other than salt fish this Lent, and it has engendered so much phlegm within me that it stops my pipes that I can scarcely speak nor breathe.”

Others, driven mad by their enforced pescetarianism, turned to drink. The Benedictine monk Robert Ripon, alive at the turn of the 15th century, was suitably scathing: “In this time of Lent, when by the law and custom of the Church men fast, very few people abstain from excessive drinking: On the contrary, they go to the taverns and some imbibe and get drunk more than they do out of Lent, thinking and saying: ‘Fishes must swim.’”

Robbed of their eggs and dairy, Medieval chefs were forced to get creative on fast days, often plumping for the same substitutes many 21st-century vegans choose. Almonds were a crucial tool in the Lenten chef’s arsenal: Lisanatti, Kite Hill and other almond cheeses have their lactose-free precursors in medieval cookbooks.

In milk form, there seemed to be no limit to what almonds could do: bind pastry; thicken sauces, even, in one staggeringly popular incarnation, pose as a hard-boiled egg.

The most staggering thing about the Mock Egg is that anyone could bear to eat it at all. A 1430 recipe book instructs chefs to fill empty egg shells with a mixture of almond-milk based jelly and a crunchy almond center, dyed yellow with saffron and ginger. It resembles an egg’s zombie counterpart, with its pallid yolk set in a mass of grey jelly. So far as texture or taste goes, the Mock Egg is a lot like baby food, and nothing at all like an egg. It might have been permissible so far as fasting rules go, but manages to be unforgivable as a foodstuff.

Mushy white pike roe was used in similar ways—some chefs would take pink salmon and stripe the two together to make imitation bacon or ham.

All of these restrictions led to some flagrant misinterpretations of what was or was not a fish. The Benedictine abbey of Le Tréport, in northern France, came under fire from the local archbishop, in Rouen, when it was discovered they were regularly noshing on puffins. These, they argued, were mostly found in and around water and must therefore be fish.

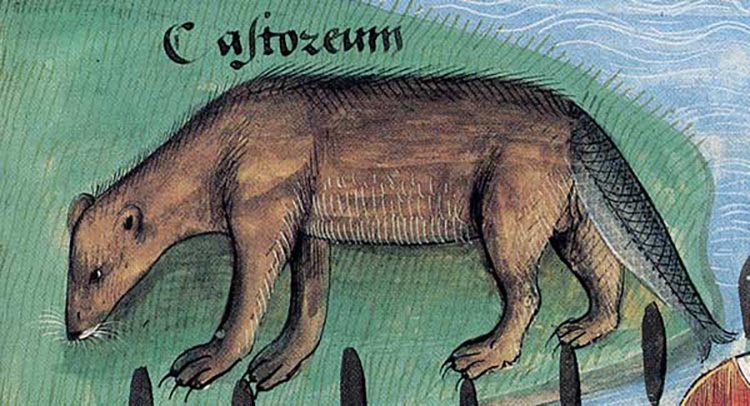

Some of these justifications were very dubious. Dolphins, porpoises and other cetaceans were mammals, but acceptable to eat as mammals of the sea (the medieval German word for dolphin is “merswin,” or “pig of the ocean,” while “porpoise” comes from the Latin for pig fish: porcus piscis).

A cookbook from a 15th-century Austrian nunnery, as translated by Melitta Adamson, suggests: “From a dolphin, you can make good dishes. You can make good roasts from it … one also makes sausages and good venison.” (These mammals, known as “royal fish” in the United Kingdom, were forbidden from commoners’ tables from 1324—as they are still, bar some arcane exceptions about whales over a certain weight.)

Other questionable permissions included the tails of beavers, which were scaly and apparently tasted enough like fish to qualify and, more horrible still, the unborn fetuses of rabbits, known as laurices.

Strangest of all was the Barnacle goose, a small black and white species that breeds in the Arctic circle and wings its way across Europe for the winters. Its intercontinental migratory habits led some Medieval birdwatchers to conclude that it hatched not from eggs but from the goose barnacles that clung to driftwood or rocks.

Sir John Mandeville, writing in the 14th century, believed these barnacles to come originally from trees that “bear a fruit that become birds flying, and those that fell in the water live … hereof had they as great marvel, that some of them trowed [found] it were an impossible thing to be.”

Impossible is correct—but the myth was widely accepted as fact. Gerald of Wales believed them to be “born at first like pieces of gum on logs of timber washed by the waves. Then, enclosed in shells of a freeform, they hang by their beaks as if from the moss clinging to the wood and so at length in process of time obtaining a sure covering of feathers, they either dive off into the waters or fly away into the free air.”

While Gerald acknowledged that these were “unnaturally produced,” he had seen so many of these barnacle birds (“more than a thousand”), for it to be in doubt. Barnacle geese, like puffins, were definitely fish.

Not everyone could swallow the story: Emperor Frederick II, the King of Italy, did some personal examination of the barnacles and coolly concluded that they did not resemble birds at all. “We therefore doubt the truth of this legend, in the absence of corroborating evidence.”

As the 16th-century Reformation took hold across Western Europe, many of these stipulations were stripped away, leaving people able to eat any meat they chose on any day of the week. But it took until 1966 for the rules to be relaxed for Catholics: after Vatican II, meat could finally be eaten on Friday—provided, of course, that some other sacrifice or good work had been substituted in its place. The effects of these rules can still be seen in today’s menus: To counteract the Friday droop in hamburger sales, McDonalds introduced Filet-o-Fish, an unexpectedly holy sandwich.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook