The Body Snatchers of Aboriginal Australia’s Legends

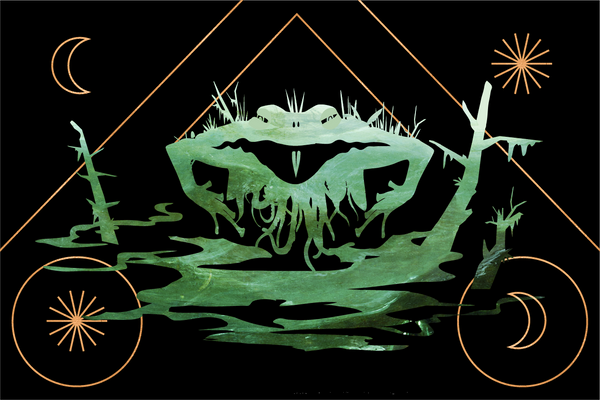

The fearsome, fanged Ngayurnangalku haunt a dry lake bed in the outback.

Atlas Obscura and Epic Magazine have teamed up for Monster Mythology, an ongoing series about things that go bump in the night around the world—their origins, their evolution, their modern cultural relevance.

It was with bemused condescension that a 2018 financial news article reported on a unique challenge facing a mining company at a new site in Western Australia. According to local Martu lore, the massive dry salt bed was home to a tribe of human-eating monsters.

This didn’t dissuade Reward Minerals. For the firm operating in the dusty Outback region of Pilbara, Lake Disappointment presented a lucrative opportunity—“the next Saskatchewan” of potash mining, for what it’s worth. But for the Martu, the Aboriginal people who have lived in Pilbara for thousands of years, Kumpupirntily, as the lakebed is known, is an area to be avoided at all costs. In the sands beneath Kumpupirntily, legend goes, is where the Ngayurnangalku live.

This name, which roughly translates to “will eat me,” provides some indication of the Ngayurnangalku’s fearsome predilections. Living under the dry lake, in their own universe, the bald, fanged, fearsome Ngayurnangalku emerge only to snatch anyone foolish enough to pass overhead with their long, curving claws. The lakebed itself doesn’t have a much better reputation. “A stark, flat and unforgiving expanse of blinding salt-lake surrounded by sand hills,” writes Australia National University researcher John Carty of Kumpupirntily. “Martu never set foot on the surface of the salt-lake and, when required to pass it by, can’t get away fast enough.”

Martu and other Aboriginal travelers are taught from a young age of Kumpupirntily’s dangers. When they must go near it, they muffle the bells on their horses, lest any sound alert the Ngayurnangalku of their presence. “It’s dangerous, that country. I’m telling you that that cannibal mob is out there and they are no good,” said Martu artist Yunkurra Billy Atkins in 2008. “When the wind is blowing we can go there, can go past. If the wind stops you can’t go any further, because [they are] there.”

Creatures, spirits, and monsters such as the Ngayurnangalku are prominent in Aboriginal Australian belief systems. “They’re so much part and parcel of everyday life,” says Yasmine Musharbash, a senior lecturer in social and cultural anthropology at Australian National University. In her extensive field work with the Yuendumu community of the Northern Territory’s Warlpiri people, Musharbash has noticed that monsters are a “part of everything,” regardless of environment or tribe. “There’s all sorts of different ones that do all sorts of different things,” she says. “Some are dangerous, some are cheeky, some are funny. They’re just part of the world that people live in.”

For Australia’s Aboriginal peoples, creatures such as the Ngayurnangalku are part of a complex spiritual worldview called “Jukurrpa” among the Warlpiri. Part cosmology, part creation myth, endlessly layered, it is commonly translated as “The Dreaming.”

With more than 300 languages, spread across a remarkably diverse variety of climates and landscapes, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia are divided into groups called “Countries,” which include all living things on the landscape, the environment, and even the language spoken. Despite this remarkable cultural diversity, however, all Aboriginal Countries share the Dreaming as a foundational way of understanding the world.

“Each Country has its own Dreaming, but all Dreamings are related the same way that all Countries are,” says Musharbash. A constellation of spirituality, the Dreaming encompasses all of time—past, present, future—simultaneously. “It incorporates everything [in] the entire world … from time to place to people, land, stars, ways of relating to each other,” she adds. “The main emphasis is [that] everything relates to everything else, across time and space.”

The non-linear, all-encompassing nature of the Dreaming explains how the vicious Ngayurnangalku are considered ancestral creatures, yet still dwell under the sands of Kumpupirntily today—and why locals will continue to avoid the area if they can help it. The same can’t be said for potash miners, though.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook