In the Andes, the Fear of Oppressors Manifests as the Gruesome Pishtaco

They seem to be a monster that made the leap from legend to the real world.

Atlas Obscura and Epic Magazine have teamed up for Monster Mythology, an ongoing series about things that go bump in the night around the world—their origins, their evolution, their modern cultural relevance.

In Inca mythology, there is a deity, Viracocha, whose name can be translated as “sea of fat.” He is the creator of the Earth and all its creatures, the maker of the sky and the sea and all the other gods. Among the Quechua people, he must be honored. “In the Andean world, indeed, blood and fat are among the essential offerings to the sacred powers: the sacrifice of slaughtered animals and the offerings of their blood constitute the opening sequence of all religious ceremonies,” writes French historian Nathan Wachtel in Gods and Vampires: Return to Chipaya. “Animal fat (generally llama fat) is one of the basic ingredients in the composition of ritual tables (mesas).”

To the Quechua, fat is sacred, and has also served medicinal purposes for centuries. It wasn’t just in the Andes that fat had such uses. Far to the north, before they reached Inca lands, conquistadors used the fat of fallen Maya to dress their own wounds, as reported by one of those conquerors, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, in The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico 1517–1521. It is easy to imagine the disgust and fear the surviving Maya must have felt upon seeing such a thing after a military defeat. It is believed similar battles during the later conquest of the Inca Empire inspired the legend of the pishtaco, a fat-sucking monster known across various countries in South America. No stories of the pishtaco exist from before the Spanish Conquest.

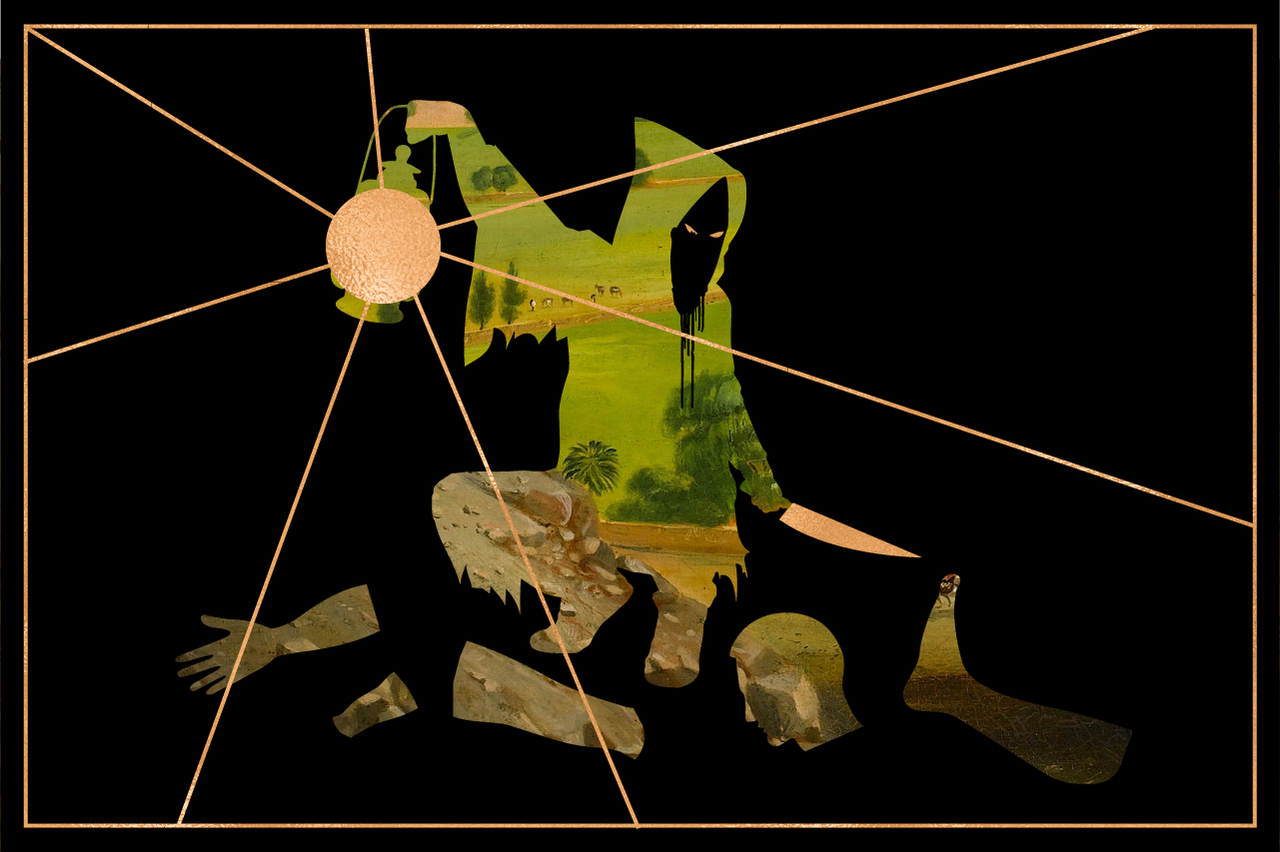

The name “pishtaco” comes from the Quechuan word pishtay, which means to “behead,” “cut the throat,” or “cut into slices.” While most Quechuan speakers are from Peru, over the years they have migrated into Bolivia, Ecuador, and other nearby mountainous regions, bringing the legend of pishtaco with them. Pishtacos are often compared to vampires, but instead of sucking blood, they suck the fat from anyone careless enough to travel alone at night.

“In the Andes, it’s thought that the vitality of the person is in the fat in their body,” says John McDowell of Indiana University’s Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology. “People who are very bony and skinny, it’s thought that they’re wasting away and they don’t have a strong life force. So the kharisiri, or the pishtaco—those are the comparable names for the same kind of figure—they come after this vital life force and deplete it.”

Over the past 500 years, there have been many descriptions of how a pishtaco might appear. It is almost exclusively male, white-skinned, and only comes out at night—not because he is unable to be in the light, but because his actions are best conducted under the veil of darkness. “I think [the pishtaco] expresses a kind of anxiety that the community has about outsiders,” McDowell continues. “After all, they’ve been through several hundred years of outsiders coming in and pushing them around. So lord knows, they probably have their reasons to be a little bit worried about outsiders.”

And the pishtaco—not unlike a conquistador—does not work alone. He is aided and accompanied by humans who help him capture, transport, and slaughter his victims, and then extract their fat. In fact, if there were no helpers of the pishtaco, perhaps there would be no tales of the pishtaco. The earliest stories come from local men who helped them in their grim task.

Spanish priest Cristóbal de Molina was the first person known to have been accused of being a pishtaco, in 1571. The locals of Cuzco refused to bring him firewood, as they feared being killed for their fat, which they believed the priests used to grease the bells they rang in the day. The 19th century brought tales of rich merchants and miners who were thought to be pishtacos. As the legend goes, they used the locals to make soap, medicine, and even grease for the machinery in their factories.

With modernity and the economic collapse of the region that came with it, it came to be documentarians, government officials, and doctors who were suspected of these practices. White doctors, for example, would arrive in marginalized communities with nurses who were known as mestizos (that is, local people who were urbanized, spoke fluent Spanish, and may have been of both European and Indigenous descent). These doctors would search for children, legend had it, to take their kidneys and eyes. Though their targets were different, the framework was the same: People were powerless to stop the use of their own bodies, by someone who was protected by authority.

These stories have continued—with rendered human fat (or sometimes other harvested parts) as a constant—though they have evolved, and moved out of the realm of the supernatural and into the real world.

In a paper in the journal Amerindia—written in Quechua and Spanish—Hernán Aguilar of the Latin American Institute of the Free University of Berlin documents modern first-hand accounts of pishtacos from their helpers, all of whom report that they were offered money to find victims. They describe seeing satis (rural people) having their throats cut with a sickle-shaped knife before being brought to the pishtacos’ home and hung upside down by their feet in a room of candles, their rendered fat dripping into bowls below them. While they all expressed horror at what they saw, many couldn’t afford to turn the money down.

According to Pishtacos: Human Fat Murderers, Structural Inequalities, and Resistances in Peru by Ernesto Vasquez Del Aguila, the most “advanced” pishtacos are able to take their victims’ fat in a far stealthier way. “Some pishtacos, it is believed, do not kill their victims instantly, but they survive for a short period of time and then die,” he writes. “These pishtacos steal the fat with great mastery, using syringes, so that their work is unnoticeable; their victims awaken without any symptoms or pain, but they get sick, become gradually weaker and after a few days they die without knowing the causes of their deaths.”

In one of the more recent, visible, documented stories of the pishtaco, in 2009, a group of men captured dozens of locals in the highland jungle region of Huánuco, more than 160 miles from the Peruvian capital of Lima. They used candles to render their fat, which was collected in old soda bottles and sold for use in rituals. This practice continued for years before three of them were captured and confessed. They led authorities to the remains of at least 60 adults. The story went national, then global.

Many of those from the mountains made it clear they believed the men to be pishtacos. “This should open the eyes of those Peruvians who live in the cities and ignore what happens in the provinces,” wrote one commenter on a news article about the killings. “This case is just one of thousands that demonstrate that these stories are real, that they are not ‘rumors.’ Limeños [those from Lima] had only skepticism.”

What connects conquistadors, missionaries, well-meaning doctors, and cold-blooded killers is what makes the pishtaco legends most frightening of all: They are not supernatural, but human.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook