The Curious Case of Monte Carlo’s Suspect ‘Suicide Epidemic’

When a moral panic swept over Europe’s seaside casino playground.

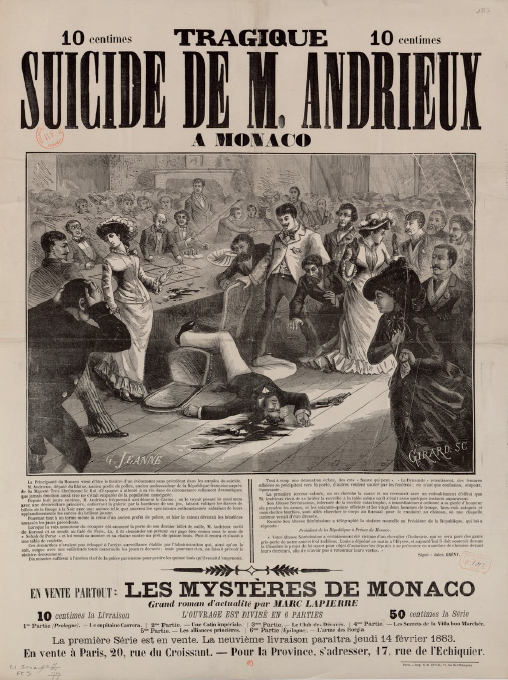

In early 1883, a grisly broadsheet shocked Paris. Below the headline “Tragic Suicide of M. Andrieux at Monaco” was an illustration of a crowd of casino-goers, horrified and transfixed by the sight of a man, toppled back from a roulette table, his head seeping blood, a revolver at his side. According to the accompanying story, a prominent French politician had shot himself after gambling away his savings in the Mediterrranean casino-resort of Monte Carlo in Monaco. But in a surprise twist, the paper reported, French President Jules Grévy sent a telegram stating that the man was actually alive and well in Paris. Finally, text at the bottom of the page revealed the whole thing—image, story, telegram—to be an advertisement for The Mysteries of Monaco, an upcoming serialized roman d’actualité (news-inspired novel).

Within weeks, the story took another turn—a real one. As documented in a report by M. Vidal, director of the Monte Carlo Casino, afternoon gambling was suddenly interrupted by the desperate cries of a Parisian woman. She had lost her fortune, and management refused to front her the 2,000 francs she demanded as a condition for leaving the property. With that, she pulled from her dress “a six-shooter revolver loaded with one bullet” and brought it to her head. Guards wrestled the gun from her hands and she was escorted “without resistance” into the director’s office, where her demand was met. “This woman has lost almost 100,000 francs in the Casino since 1881,” concluded the report. “She admitted that she had no intention to kill herself but knew that there would be no better way to get what she wanted.”

Whether threatened or carried out, real, exaggerated, or imagined, suicide stories like these darkened the reputation of Monte Carlo for the first half-century of its existence. It’s fitting in a way. Excess, risk, desperation—they’re all part of Monte Carlo’s origin story.

In 1855, with her tiny Mediterranean monarchy facing financial ruin, Princess Caroline of Monaco hatched a rescue plan: build a seaside casino resort for all of Europe. At the time, the continent was in the grip of Christian moralism, with most nations outlawing gambling in public. This left Monaco as the only game in Europe, and after 10 years of casino mismanagement, it found a savior and champion in Francois Blanc.

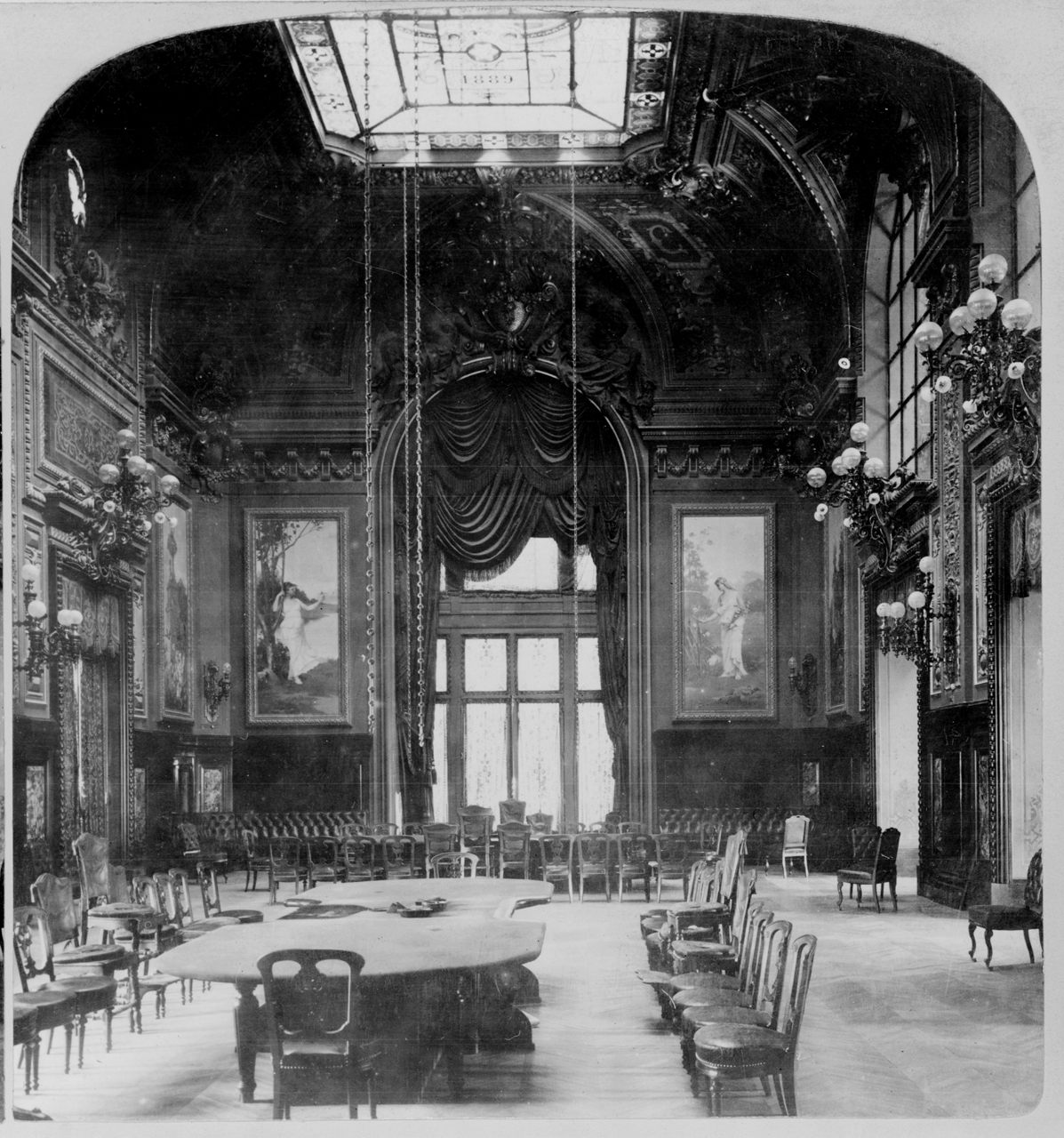

Years earlier, Blanc had gamed the French stock market—earning him both a criminal conviction and popular awe, which he parlayed into a booming casino/spa in Bad Homburg, Germany. Monaco’s newly christened quarter of Monte Carlo, and its eponymous casino, would become his next empire. He brought professionalism to the gaming rooms and made a big show of Monte Carlo’s “honest odds.” And with the addition of a fine hotel, spa, grand opera house, lush tropical gardens, and seaside pigeon shoot, he gave the resort an air of aristocratic luxury. In 1870 alone, Monte Carlo boasted 150,000 visitors. “It was worldly and charming,” writes Mary Blume, author of Cote d’Azur: Inventing the French Riviera, “but its heart, if it had one, was clearly in the wrong place: the cathedral of Monaco was completed in 1886, well after the casino and the opera.”

Their pockets lighter, the hordes often spilled over into neighboring Nice, France, where the locals were less than thrilled. Some opposed gambling altogether, while others simply lamented that they couldn’t profit from it themselves. In turn, there emerged from Nice a growing wave of anti–Monte Carlo news and propaganda. By 1875 it included vivid claims of an epidemic of gambling-induced suicides.

In 1876, the Anglican Bishop of Gibraltar—denied in his request to build an Anglican church in Monaco by Prince Albert, a Roman Catholic—delivered a blistering polemic that referred to Monte Carlo as “a scandal not only to our religion, but also to the civilization of this nineteenth century.” Gambling, he seethed, causes “such a selfish heartlessness of character that, as was seen the other day, players will immediately continue their game after one of their party has committed suicide before their very eyes.”

Disgust and opprobrium with Monte Carlo’s reputation—fair or otherwise—swept across Europe and beyond. Over the following decades, these suicide tales made for regular news worldwide—as incessant as they were gruesome—some confirmed by death records, with far more utterly unverifiable. An “Italian nobleman” hung himself from a palm tree. A “Hungarian gentlemen” stabbed himself to death. Despondent gamblers guzzled carbolic acid and prussic acid, jumped from seaside cliffs, hotel windows, the rack-railway viaduct, a ledge high above the Sainte-Dévote Chapel. A Parisian woman strangled her two children before doing herself in. In his “dying agony” after shooting himself, a German overturned a candle in his hotel room and “was cremated before the fire brigade arrived.” Two young lovers asphyxiated themselves with charcoal fumes. Their purported suicide note read, “We have enjoyed the present; we have ruined our future at Monte Carlo; we prefer death to shame and misery.”

Routinely (and perhaps tellingly), the papers reported the victims’ gambling losses with precision—always huge—and offered a running tally of suicides to date. “The Monte Carlo black list, or rather death-toll, for the month of June,” reported the Scotsman in 1888, “is considerably lower than average … 23.”

Another standard story template was the tale of the “cover-up,” of casino management going to lengths to conceal the epidemic. Cold-hearted croupiers whisked fresh corpses through a hidden “sliding panel.” Guards plucked them from the gardens with a long rake. Bodies were mailed out of Monaco, sunk at sea, wedged into pianos. Blanc and casino management bought media silence, insisted Niçoise reports, and Monégasque authorities fudged official records. According to one recurring tabloid rumor, casino staff lined the victims’ pockets with cash before police arrived, so gambling losses could not be blamed. (Supposedly scam artists took advantage, splattering their faces with red paint, playing dead and waiting for the payoff, then dashing away richer.)

Internal correspondence from the casino archives suggests that some of these tales contained at least a kernel of truth. In one missive, for example, management complained that a suicide victim’s body had been left outside all night because the lazy guards went home before the casino’s midnight closure, leaving “no surveillance at the time when it would be most necessary.”

Skeptics raised doubts about the quantity of these suicide stories, and in response, tell-all books, tabloids, and soft-news outlets such as Cassell’s Saturday Journal doubled down. Their correspondents gossiped of a secret “suicides cemetery” on the steep mountainside above Monte Carlo, at the base of the promontory called Tête de Chien. Some claimed to have visited, illustrations were made, and an unnerving gravedigger quoted by a British wire service: “All these forty graves I have dug myself. They are all mine, and so are the people in them.” Depending on the story, the graves of suicides were marked with numbers, an “S,” or not at all. Over the years, their reputed location moved, from high-altitude isolation to a subsection of the official Monaco Cemetery, then to scattered spots all over the cemetery to avoid suspicion. U.S. State Department records of two actual suicides of Americans in the 1930s point to the likeliest truth behind some of these rumors: Their bodies were temporarily interred in numbered graves before being shipped home.

These stories, as one might expect, added to the fascination with Monte Carlo, and became a draw for tourists. Casino-goers asked to see (or sit in) the infamous “suicide chair” at the roulette table, rumored to have claimed 17 souls. Outside, constant gunshots made it seem like a suicide mania had gripped the entire principality (though it was probably just the pigeon shoot). Painter and gambler Edvard Munch sought out a recent suicide spot: “I had to look at the earth behind the bush as though I would still see blood.” And for those who couldn’t make the trip, an 1883 wire report, printed in the Ediburgh Evening News, promised that a Monte Carlo suicide waxworks, based on actual photos, was soon to open in Paris. (It never did.)

For all the hype, according to historian Mark Braude, author of Making Monte Carlo: A History of Speculation and Spectacle, there is no evidence that suicide rates were ever much higher in Monte Carlo than elsewhere. Some tales were true, others were surely invented, and still more at least embellished. They may have just drawn more attention because of where they took place. “It’s always about more than the suicide,” Braude says. “It’s about movement … people throwing off the shackles of home … going to this place and running wild.” In the young republic of France, in particular, the unease with Monte Carlo and its suicides was acutely political and moral. “Here are these ultimate rejections of everything having to do with community and the nation. And what has caused it?… The evils of speculative capitalism—people who want something for nothing and want to get rich without working.”

Today, suicide no longer haunts Monte Carlo. It is a tax haven for the world’s super-wealthy, its small harbor clotted with giant yachts. Monaco Cemetery is still there, and now involves a concrete hike—up staircases and winding streets, through narrow canyons of apartment towers, along the well-fenced ledges above Sainte-Dévote Chapel, past luxury car dealerships, police checkpoints, and public defibrillators (Monaco has the world’s oldest median age). As it did a century ago, the cemetery still commands a sweeping Mediterranean panorama. Josephine Baker is buried there, as is Sir Roger Moore. But there are no graves marked with a number or an “S.” The “suicides section,” if it ever existed, is nowhere to be found.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook