Why Newfoundland Is Turning Its Moose Into Bologna

And salami. And pepperoni.

Newfoundland is overrun with moose. The provincial government estimates that about 120,000 currently wander this Canadian island roughly the size of Tennessee, the most concentrated population in the world. The largest of the deer family, a full-grown moose weighs between 600 and 1,200 pounds. An animal that big and that common creates problems both for Newfoundland’s delicate ecosystems and its people. Estimates put moose-vehicle collisions at about 600 a year.

To help control the exploding moose population and reduce their impact, the province issued 29,260 moose hunting licenses for the most recent season. Some 85 percent of those hunters went home with a moose. On its website, Hunting Newfoundland Labrador claims “success rates better than most marriages.” Some successful hunters take their moose to local butchers for cutting into steaks, roasts, and ribs. And some of those butchers buy moose meat from hunters to make a unique Newfoundland delicacy: moose bologna.

At Bidgood’s Supermarket in the capital city of St. John’s, the store buys moose from hunters, sends it to nearby Morris Foods to be processed into bologna, then brings it back to sell. Even community groups are getting in on the action. Some 500 of those moose hunting licenses went to not-for-profit organizations. Hunters volunteer to hunt moose and sell the meat to stores such as Bidgood’s to fundraise.

“It’s fabulous,” says Diane Knee, who works at Morris Foods. “All bolognas have the same consistency, but the flavor is different from beef and chicken.” While moose is the main ingredient in Morris Foods’s moose bologna, it’s mixed with pork, beef, and chicken, flavored with onion and garlic powders, mustard, smoke, and secret spices. As for moose bologna’s unique flavor, Knee says, “It’s all about the actual meat itself. Some moose is really gamey. I’ve eaten moose that tastes like tree bark and others that you wouldn’t tell the difference from beef.”

Moose bologna is no passing fad. Neither is it an ironic or novelty food, purchased once as a conversation starter. Moose bologna brings together two of the best-loved foods on Newfoundland. Among the Canadian provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador easily takes the cake when it comes to the consumption of what the English writer John Collins referred to in 1682 as a newfangled spicy sausage from Italy. Inexpensive, long-lasting bologna is a staple in Newfoundland kitchens, where it’s fried, baked, stewed, canned, curried, smothered in gravy, and barbecued. In their typical self-deprecating humor, Newfoundlanders have long told tall tales about hunting the great wild bologna, the source of the so-called “Newfie steak.”

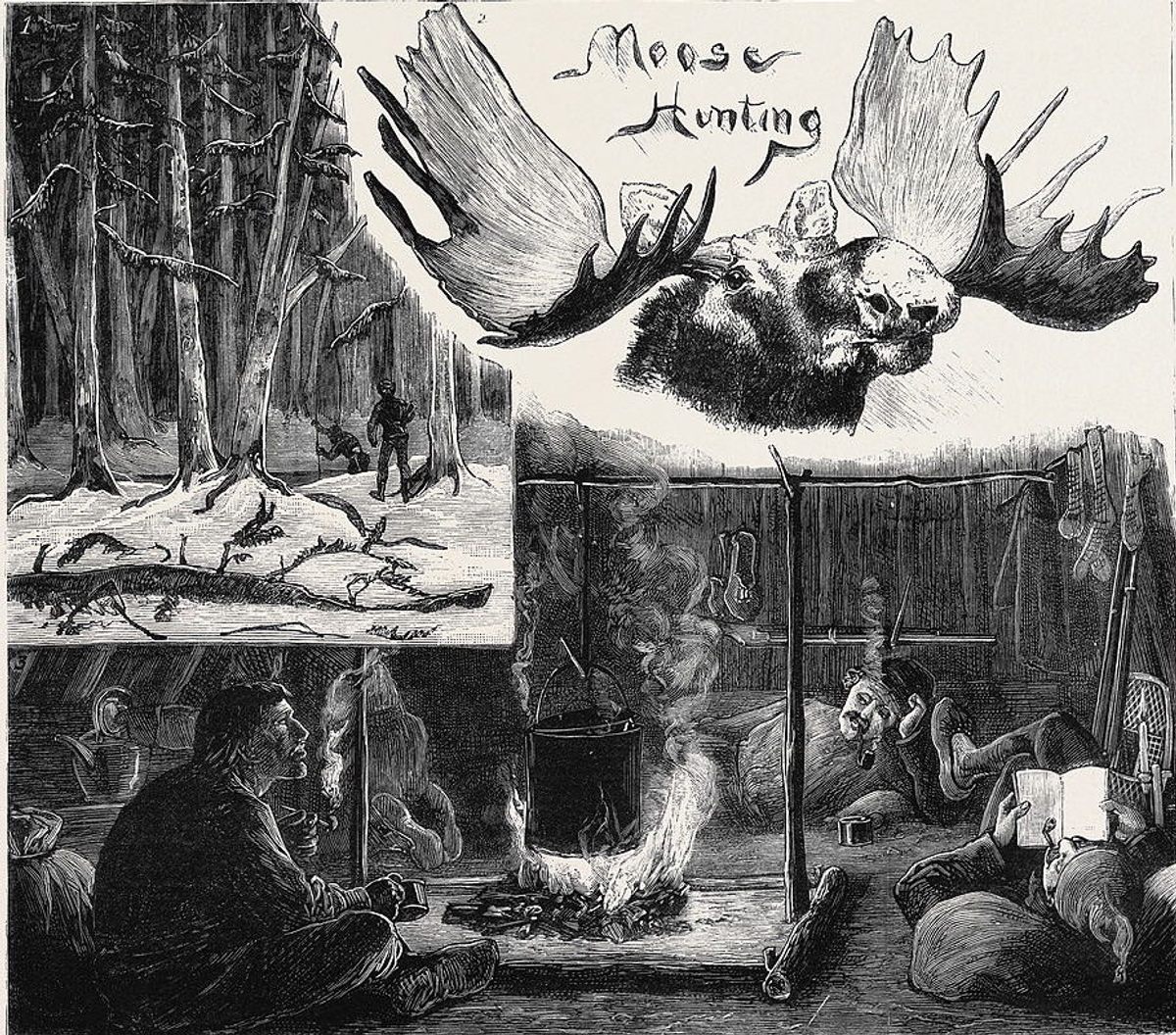

The Newfoundland love affair with moose meat, on the other hand, goes back to the early 20th century, when the animal was first introduced to the island. When the province was still a British colony, some were keen to develop hunting tourism. Following a visit to Canada, the British military officer and keen hunter Captain Richard Dashwood published Chiploquorgan: Or, Life by the Camp Fire in the Dominion of Canada and Newfoundland, in which he wrote that “it would be an excellent plan and one worthy of the consideration of the Newfoundland Government, to turn up moose in the island. In a few years they would become numerous.”

Oh, how right he was. In 1904, two bulls and two cows captured on the mainland were released in western Newfoundland, on the shores of Grand Lake. In 1935, the island’s first moose hunting season opened, beginning the Newfie love affair with moose meat. Moose have been around long enough to enter local lore and music, such as the musical comedy group Buddy Wasisname and the Other Fellers and their song, “Gotta Get Me Moose B’y,” which chronicles the messes a moose hunter gets himself into.

But in Gros Morne National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site on the island’s western coast, moose are causing damage to the park’s ecosystem. The big herbivores are over-browsing the vegetation, changing the mix of trees by preventing some species from maturing. As a result, the park’s bears, lynx, and coyotes suffer the effects of a changing landscape.

Through their company Tour Gros Morne, Ian and Rebecca Stone are doing their part to reduce the impact of moose on the park. They lead multi-day hikes into the wilderness and culinary day tours around the nearby villages.

A passionate cook, Rebecca whips up honey garlic moose meatballs, sticks of moose jerky, and traditional bottled moose meat for tours and events. “The meatballs are infused with cumin, thyme, and green onions, while the sauce has honey, soy, and Chinese five spice,” she says. The jerky is lean and flavored with Irish whiskey, honey, soy, and thyme, a mix that balances the gaminess of the wild meat.

Ian and his friends hunt moose within park boundaries. His license is just one of the 600 issued for Gros Morne National Park. Another 90 are available for hunting inside Terra Nova National Park on the island’s north coast. All are issued to mitigate the damage of moose browsing on the parks’ delicate ecosystems.

Hunting is helping, Ian says. “We’re the only national park in the country you’re allowed to hunt in, so moose is extremely prevalent in everybody’s freezer.” But while some of the Stones’s tours include a search for wild moose, they aren’t hunting guides. “In Gros Morne, the forests are recovering because of the excellent management of the moose population by Parks Canada,” Ian says. “We’re happy knowing whatever moose we used on our tours has come from a healthy and properly managed source.”

But in the end, Newfoundland’s moose are here to stay. According to Craig Renouf, the media relations manager for the Newfoundland and Labrador’s Department of Fisheries and Land Resources, “They are now considered a naturalized species and are managed as such,” albeit with hunting promoted as an element of population control. “We are aware that residents make a host of products from moose meat and utilize it as a dietary staple,” Renouf says. In other words, the moose hunt—and moose bologna—are part of the solution to Newfoundland’s antlered dilemma.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook