The Enduring Mystery of James A. Garfield’s Immigration Scandal

Instead of emails, there was the Morey letter.

On October 20, 1880, just a couple weeks before the U.S. presidential election of that year, the New York newspaper Truth published a letter made up of two short paragraphs signed by James A. Garfield, the Republican candidate for president. Those two paragraphs could have been, as the paper wrote a few days later, Garfield’s “political death warrant.”

Addressed to one H.L. Morey, the letter concerned the immigration of Chinese laborers to America. “Individuals or companies have the right to buy labor when they can get it cheapest,” the letter read. “We have a treaty with the Chinese Government… I am not prepared to say that it should be abrogated until our great manufacturing and corporate interests are conserved in the matter of labor.”

More than 135 years later, that might sound reasonable enough. But in the 1880s, America was caught up in a cascade of nativism and anti-Chinese sentiment. To parts of the American populace—in particular, voters in California and other western states, where Chinese labor was seen as a threat to white workers—this was an outrage.

The “Morey letter,” as it quickly came to be known, was a classic October surprise, an attack in the waning days of a campaign meant to land a death blow. But the letter also raised some pressing questions. First of all, who was H.L. Morey?

The 1880 election was going to be very close. It was the first election after the end of Reconstruction, and while the Republicans were still the party of Lincoln, they were divided among themselves. Garfield had been nominated at the longest Republican National Convention ever, after 36 rounds of balloting in which neither of the two leading candidates, Ulysses S. Grant and Senator James Blaine, was able to command a majority. Democrats controlled the South and much of the West. To win, Garfield would have to sweep the North and the West Coast.

“Communication was very poor compared to today,” says Kenneth Ackerman, the author of Dark Horse, a history of Garfield’s election and assassination. “There was no TV and no radio. Even the telegraph was relatively new. These were weakness in the system that a clever plant could take advantage of.” Start a rumor close to the election, in other words, and even if it was grossly untrue, your opponent might not have enough time to fight back.

Garfield was already a bit vulnerable to a nativist attack on the issue of Chinese immigration. The Burlingame Treaty referred to in the letter allowed for unlimited immigration from China; just the year before, President Rutherford B. Hayes had vetoed a bill that would have limited the number of Chinese immigrants to 15 people per ship. As a congressman, Garfield had supported the veto on the grounds that breaking the treaty could endanger American missionaries and other ex-pats living in China.

But the letter put him solidly on the pro-immigration side of the issue, and Democrats immediately took advantage of it. Garfield’s opponents had the letter translated into different languages. They made hundreds of thousands of copies and sent them by train to California, where political operatives would hand them out at schools and in front of mills. In Denver, there was an anti-Chinese riot in the city after the letter was printed in the local paper.

Garfield, at first, kept silent. Working from his home in Ohio, he hoped the scandal would quiet down if he didn’t engage. But he also had a nagging doubt. He didn’t think he had written the letter, but he wasn’t sure. During the campaign, he had signed so many letters, and it was possible he’d signed this one, too. He dispatched a secretary to Washington to search through his files there.

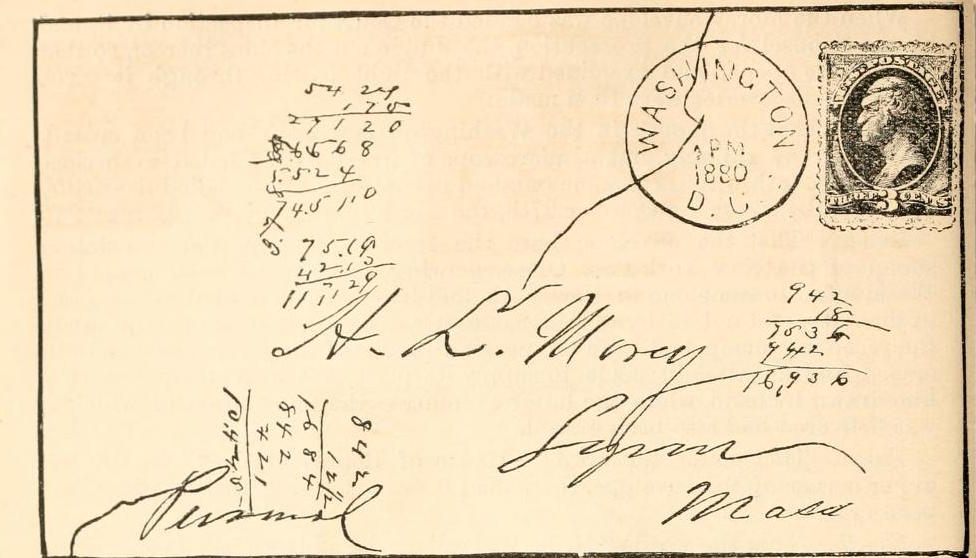

Meanwhile, the Republican Party had started to investigate this H.L. Morey. The day after the Morey letter was published, newspapers were already reporting doubts. Morey was supposed to live in Lynn, Massachusetts, about 10 miles from Boston, and have been part of the Employers’ Union. But business leaders in Boston said that no such organization had ever existed, and they knew of no H.L. Morey. Still, the Truth continued its campaign against Garfield; on October 23, the paper published a facsimile of the Morey letter on the cover of the paper. Pressure on Garfield increased—if he hadn’t written the letter, he needed to denounce it.

Garfield took a risk. He went public with a denial: he hadn’t written the letter. It wasn’t until October 25 that he received a copy of the Truth with the facsimile on the cover. Immediately, Garfield was reassured. The letter wasn’t in his handwriting nor that of his aides. Not long after, word came from D.C.: there was no copy of the letter in the files there. The letter was a fraud.

All of which led to the second question at the center of the scandal: Who had actually written the letter?

The Republican Party didn’t have much time to gain control of the story. They printed copies of Garfield’s denial and had them shipped to California “on a special car to San Francisco,” the San Francisco Chronicle reported. “The trip across the continent will be much the fastest ever made by any train.” (No one noted that those crucial, speedy trains were likely to travel on tracks built by Chinese labor.)

Garfield lost California, by just 144 votes. But he won the election. Although he had a wide margin of victory in the electoral college, in the popular vote Garfield’s margin of victory was the slimmest in the history of U.S. presidential elections: fewer than 10,000 votes separated the two candidates.

The scandal of the Morey letter dragged on for years after the election, though, even after Garfield was assassinated (for unrelated reasons) six months into his term. The journalist who originally published the letter, Kenward Philp, was put on trial for libel and forgery. Described by a contemporary paper as “a little fellow with a high forehead,” he’d been known as a political prankster, which didn’t help his case.

But Philp was acquitted of the crime. The only person to go to jail was one of two witnesses allegedly paid off by the Democratic Party to testify that they knew H.L. Morey. But Morey did not exist and never had; eventually the two witnesses admitted as much. One was found guilty of perjury and sentenced to 8 years in Sing Sing. “In the author’s opinion, which he cannot document, it was probably the prankster Kenward Philp who penned the Morey letter,” wrote the historian Ted C. Hinckley, in one of most thorough accounts of the scandal.

A contemporary investigation, published in 1884, blamed a different culprit, a lawyer with “an innate love of intrigue, and a craving for notoriety.” In the end, no one knows for sure who wrote the Morey letter, described by a Republican lawyer at the time as “the most extraordinary and infamous achievement in political fraud-doing ever perpetrated by any political party in this country.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook