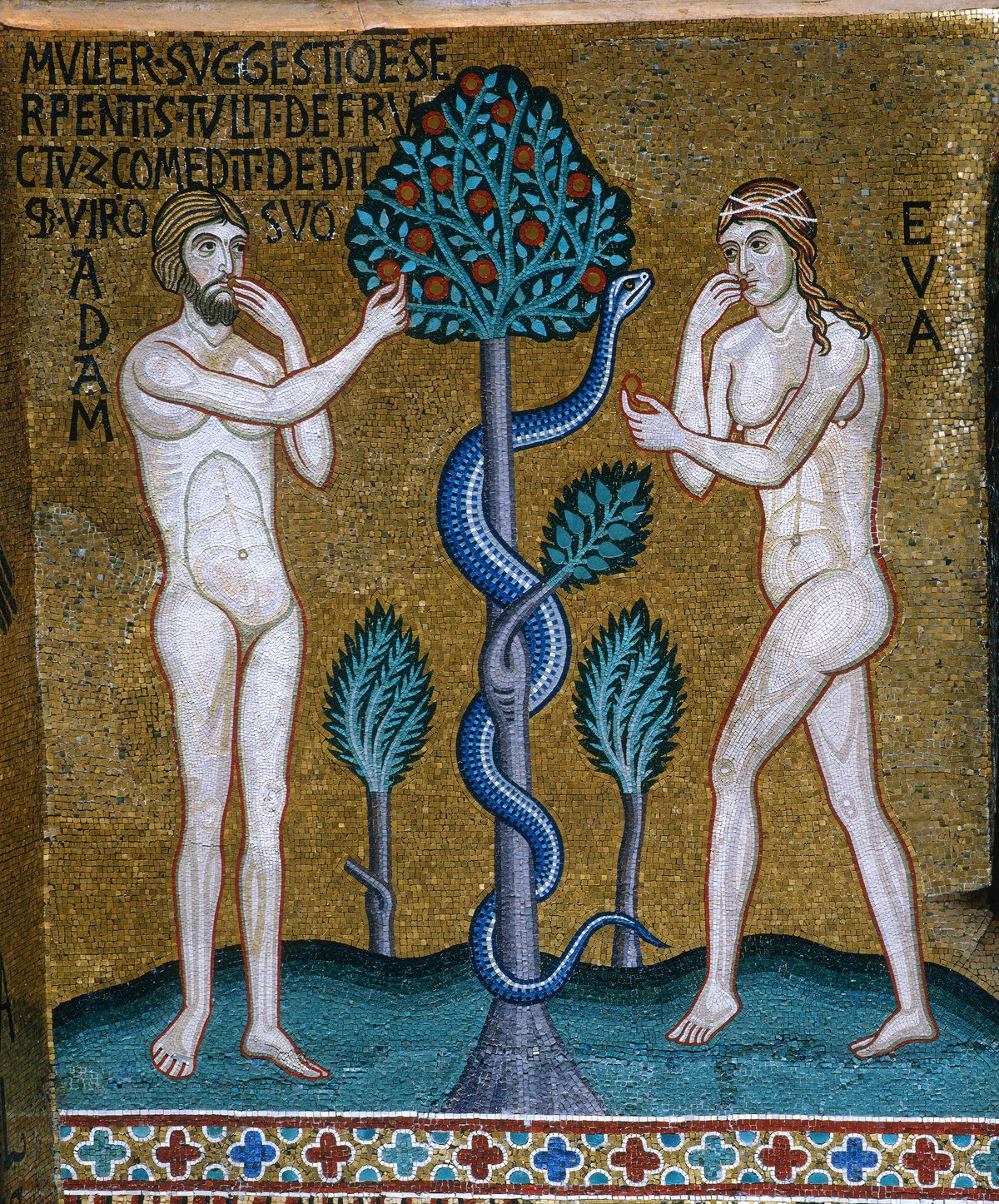

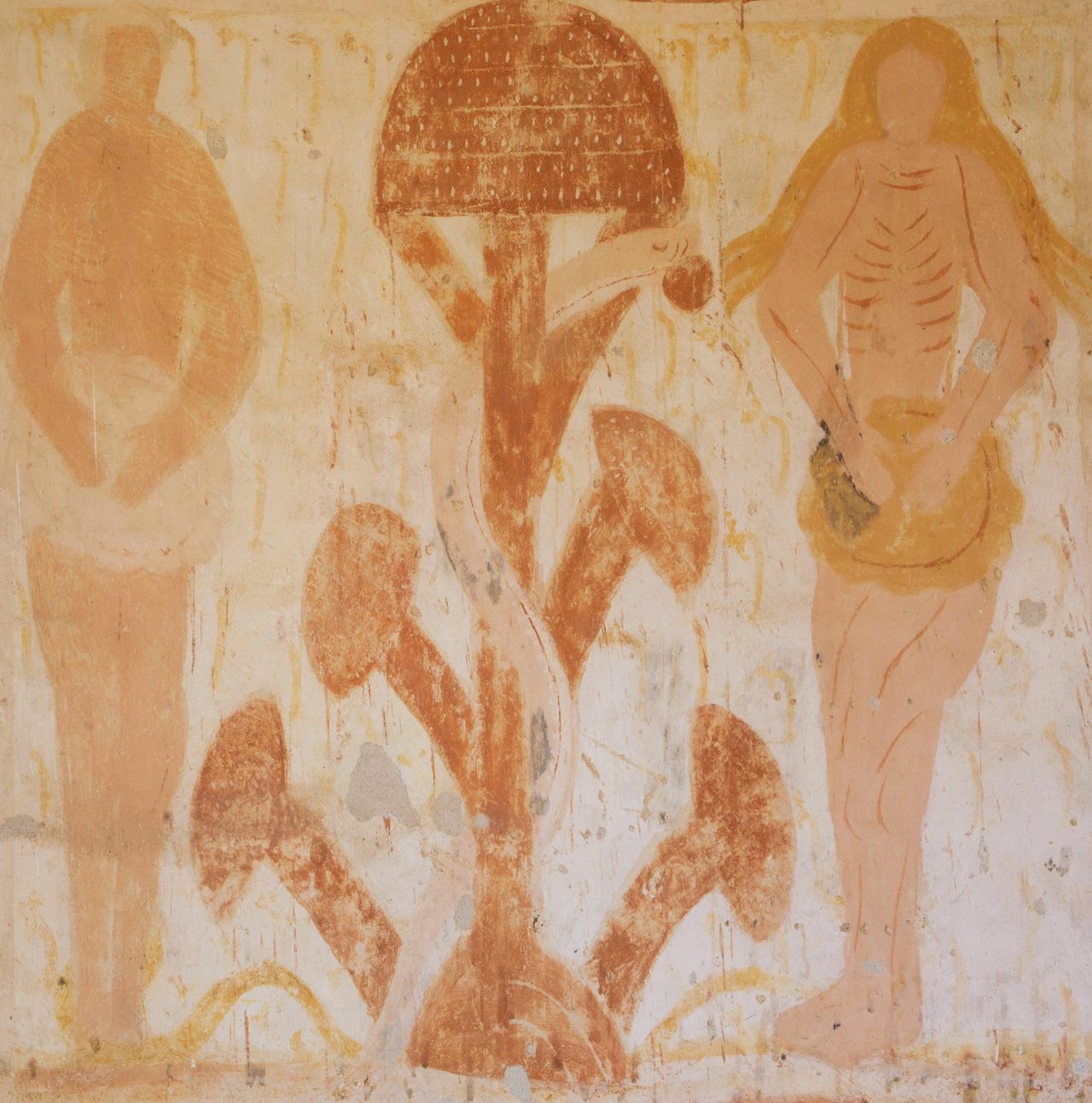

Does This Medieval Fresco Show A Hallucinogenic Mushroom in the Garden of Eden?

Controversy over what’s depicted in the image, and what it may say about early Christians, has raged for decades.

Adam and Eve stand in the Garden of Eden, both of them faceless. Eve’s ribs are bold slash marks, as if the artist wanted her to appear almost skeletal. But that is not the strangest thing about this faded 13th-century fresco inside France’s medieval Plaincourault Chapel. Between Adam and Eve stands a large red tree, crowned with a dotted, umbrella-like cap. The tree’s branches end in smaller caps, each with their own pattern of tiny white spots.

It’s this tree that has attracted visitors from around the world to the sleepy village of Mérigny, some 200 miles south of Paris. Tourists, scholars, and influencers come to see the tree that, according to some enthusiasts, depicts the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria. Not everyone agrees, however, and controversy over the fresco has polarized researchers, helped ruin at least one career, and inspired an idea—unproven but wildly popular, in some circles—that early Christians used hallucinogenic mushrooms.

The question of what was painted on the back wall of Plaincourault goes back at least to 1911, when a member of the French Mycological Society suggested the thing sprouting between Adam and Eve was a “bizarre” and “arborescent” mushroom. The idea that the Tree of Life was actually A. muscaria pops up in the 1925 book The Romance of the Fungus World, which presents a “curious myth” about the Plaincourault fresco depicting the hallucinogenic mushroom, though there is no suggestion of its use by early Christians.

A quarter-century later, the earlier mentions lured R. Gordon Wasson to see the fresco for himself. Wasson was a PR exec in banking, and also an amateur mycologist. Although he had no formal training in the field, he’s known today for his prolific writing on mushrooms, particularly of the hallucinogenic variety, and fungi-focused travels, some of which were secretly funded by the CIA, which had its own interests in the topic. In 1952, when Wasson saw Plaincourault for himself, he wasn’t convinced, and sought the opinion of Princeton art historian Erwin Panofsky. The scholar was blunt. “The plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms,” Panofsky wrote.

The idea persisted, however, and was loudly revived in 1970 by John Marco Allegro, a scholar of ancient languages at the University of Manchester. In his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, Allegro argued that Christianity itself had derived from a fertility cult whose members ingested hallucinogens. He called the Garden of Eden story “mushroom-based mythology.” His visual evidence was the fresco at Plaincourault, in which “Amanita muscaria is gloriously portrayed,” he wrote. Allegro was already a controversial figure: He had been publicly criticized by colleagues on a team translating the Dead Sea Scrolls for his overly imaginative interpretations. But The Sacred Mushroom was the final nail in the coffin of Allegro’s career.

Speaking to Time Magazine, one scholar called the book “a Semitic philologist’s erotic nightmare.” Other critics included Wasson, who wrote, “One could expect mycologists, in their isolation, to make this blunder. Mr. Allegro is not a mycologist but, if anything, a cultural historian.” Despite the broad and negative reaction to the book, Allegro’s interpretation of the Plaincourault fresco lives on, attracting new believers.

Two of the fresco’s current champions are Julie and Jerry Brown, neither of whom are mycologists or art historians. Jerry is an anthropologist at Florida International University, where he teaches a course on psychedelics and culture. Julie is an integrative psychotherapist. The Browns believe that Allegro got a few things right, namely, the idea that early Christianity could have incorporated the use of psychoactive plants, and that mushrooms depicted in Christian art are proof of that use. Jerry Brown calls the fresco at Plaincourault “seminal” to this argument.

“If Allegro were right, and Plaincourault did represent a stunning example of a psychoactive mushroom in a late 13th-century fresco, then entheogens [psychoactive substances] could be seen as integral to the origins of Judeo-Christianity with a usage persisting at least into medieval times as evidenced by this fresco,” says Brown.

While many religions past and present incorporate some form of psychoactive plant, “as yet, there is no convincing biomolecular archaeological evidence of the use of hallucinogens by early Christians,” says Patrick McGovern, the scientific director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project at the University of Pennsylvania.

Art historians are also skeptical that the medieval fresco is secretly showcasing Christianity’s psychedelic roots. “I can assure you that the arboreal form at Plaincourault, or elsewhere for that matter, in no way references a particular species of mushroom,” says Marcia Kupfer, an independent scholar of medieval art and author of Romanesque Wall Painting in Central France.

Elina Gertsman, an art historian at Case Western Reserve University, says she’s not one to shy away from well-placed speculation, but even she can’t get behind the idea that the tree is a hallucinogenic mushroom. Instead, she says, medieval artists may have been experimenting with new ways to stylize trees. There are countless examples of medieval images where artists did this, including lions that appear to be wearing glasses, or elephants with mitten-like feet. “I think you will be hard-pressed to find a specialist in medieval art who disagrees with me and subscribes, instead, to the psychedelic Christianity idea,” Gertsman says.

Jerry Brown has heard the art historians’ assessments and remains unswayed. “As Louis Pasteur said, chance favors the prepared mind,” says Brown. “My mind, having taught psychedelics for decades, recognized it.”

There is no shortage of prepared minds out there: The idea that the Plaincourault fresco depicts A. muscaria as the Tree of Life thrives on social media posts, blogs, and in digital image collections. Some of the sites alter the image of the tree to enhance its resemblance to the mushroom, boosting the red color or employing other “pretty blatant manipulation,” says Gertsman.

The idea of Plaincourault depicting a mushroom tree got another boost recently from comedian Joe Rogan, whose podcast, The Joe Rogan Experience, was the top podcast on Spotify in 2020. “That is an original fresco from France, 13th-century fresco depicting Adam and Eve and the Tree of Knowledge,” Rogan told his millions of listeners. “That mushroom is a mushroom called the Amanita muscaria.”

If the idea of the Plaincourault fresco depicting a hallucinogenic mushroom has been debunked, repeatedly, by scholars in the best position to interpret it, why does it persist? The reason may be a combination of shifting societal attitudes and the very human tendency to see what we want to see.

Americans, for example, are becoming more open to the idea of psychedelics, says Ido Hartogsohn, the author of American Trip: Set, Setting and the Psychedelic Experience in the 20th Century. In 2017, 53 percent of a nationally representative sample of 1,145 Americans said they supported medical research into psychedelics. In 2020, Oregon decriminalized psilocybin, a hallucinogenic compound found in several types of mushroom, and legalized it in therapeutic contexts—the first state to do so.

A growing acceptance of hallucinogens in the mainstream now may make many of us more willing to believe that they were used in the past, even in cultures and periods where hard evidence is lacking. “In some cases, advocacy of psychedelics can lead some to find clues for their existence everywhere, even when the supporting evidence is quite speculative in nature,” say Hartogsohn.

For the last 100 years, people have been seeing mushrooms when they look into the image at Plaincourault. Today, it may be easier than ever to see them, even if they’re not really there.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook