Looking Back on NASA’s Vivid 1970s Visions of Space Living

Feast your peepers on these artistic interpretations of a colonized cosmos.

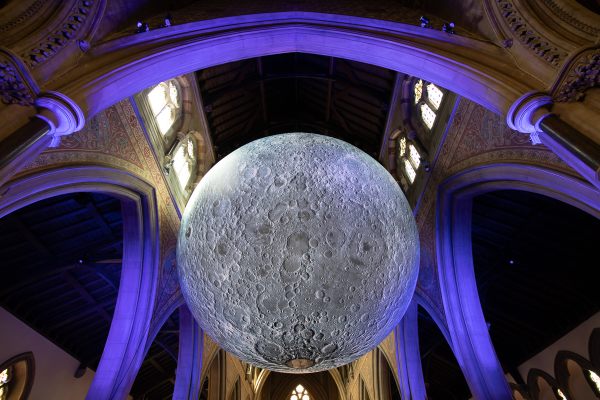

Earlier this year, California-based aerospace startup company Orion Span announced its plans to launch a “luxury space hotel” in 2021. Aurora Station, the commercial space getaway orbiting 200 miles above Earth, will accommodate four guests and two crew members at a time. For $9.5 million, you too can stay there for 12 nights.

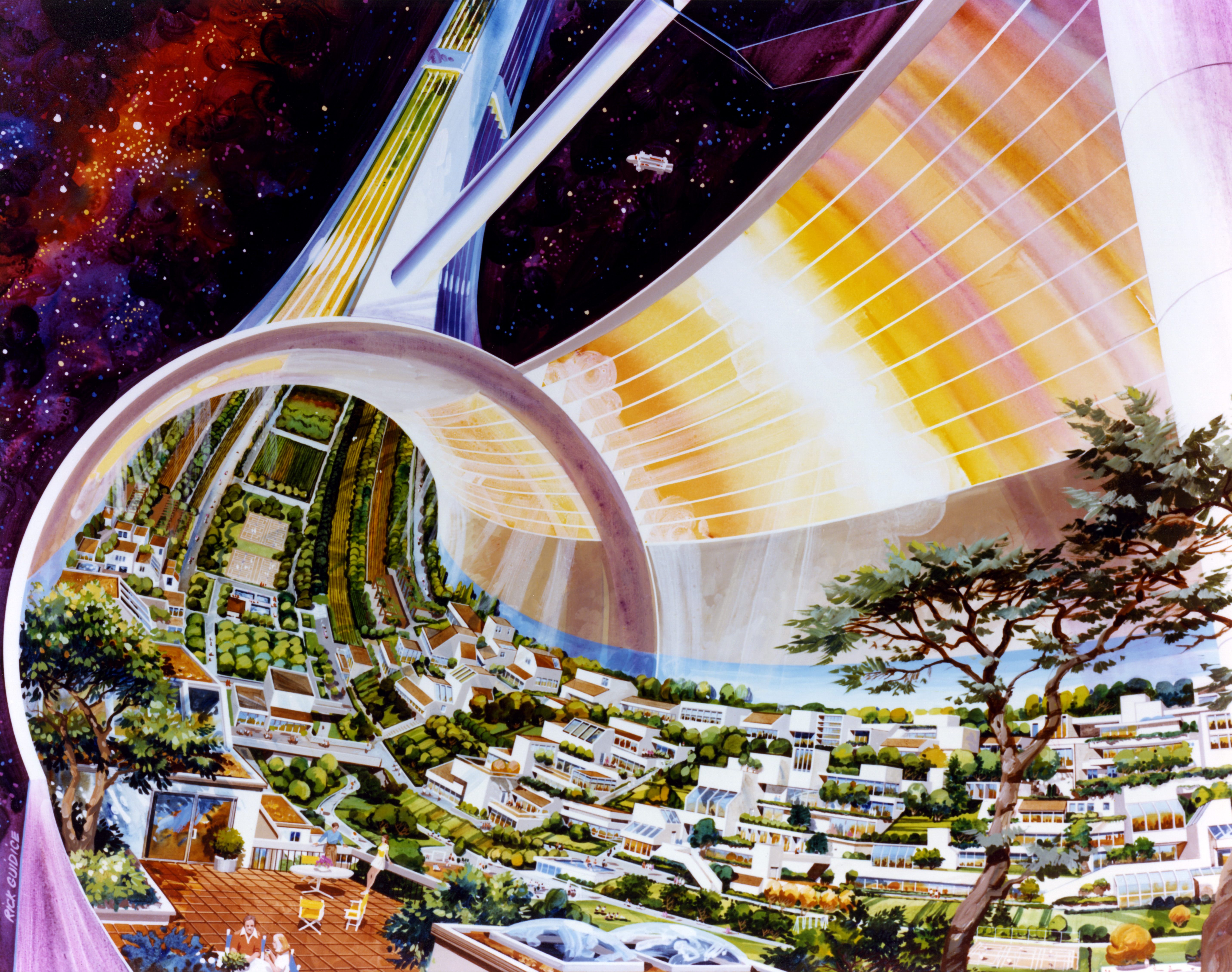

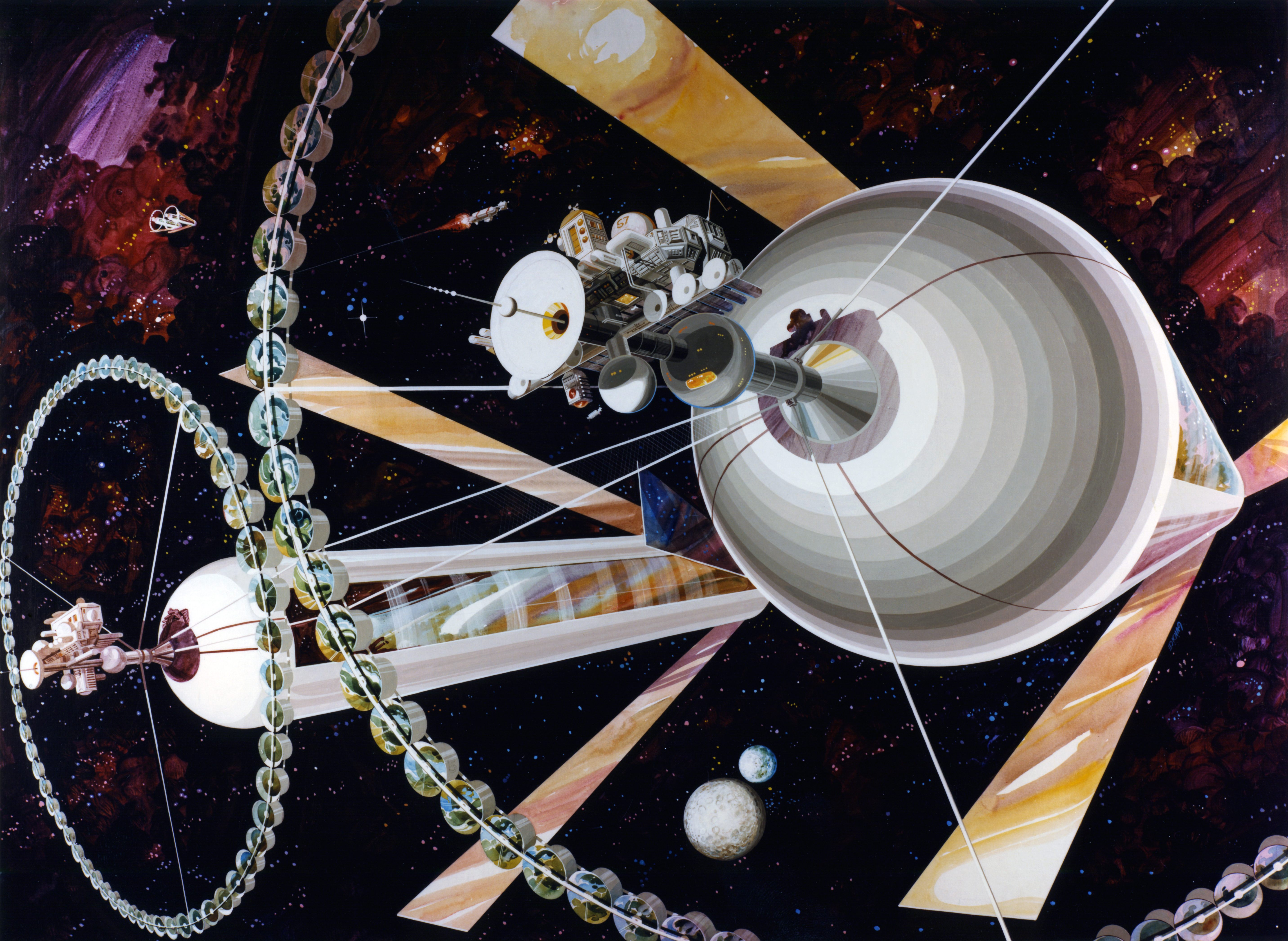

Though the possibility of future housing in space is a shiny idea, it’s hardly novel. Scientists and engineers have been exploring how humans might permanently colonize space for decades. Rick Guidice, a NASA-affiliated artist during the 1970s, generated visuals of what space accommodation might look like.

In the summer of 1975, at NASA’s Ames Research Center located in Mountain View, California, a team of NASA and Stanford University researchers led by physicist Dr. Gerard O’Neill imagined a future world with space colonies. Could human beings survive living in permanent, free-floating structures away from Earth? O’Neill and his team could theorize about it, and calculate a cost-benefit analysis of leaving Earth for another fold in the universe, but they’d need to call on illustrators to truly see the possibilities.

NASA was a longtime commissioner of Guidice’s work, and during the 10-week summer study where participants worked on this space settlement project, Guidice was tapped to render images that would illustrate the feasibility of living in space. O’Neill had been studying space colonization for the past six years at Princeton, and according to Guidice, had “pretty much defined systems for how to build habitats in space on a large scale.” In response to this research, NASA provided Guidice with technical information and simple diagrams of what these possible future settlements might look like, and then he interpreted the data into detailed pencil sketches.

“Of course I realized this was a very important opportunity to really do something special,” he says. After several weeks* of research and revision, Guidice ended up with his first—and favorite—painting: the double cylinder space colony.

The team of scientists devised multiple approaches to space habitation, so Guidice dreamt up several illustrations as a way to visualize them. “Gerard O’Neill wanted [the habitats] to look like an English countryside,” Guidice remembers. “Not very dense.” Full-color renderings, drawn and hand-painted with acrylics, were presented to the scientists on large-scale illustration boards, but were initially thought of as purely auxiliary material rather than art.

“What’s interesting is that the paintings at the time were just illustrations in support, and later on they’ve taken on a life of their own—they’re what most people recognize,” Guidice says. “It tells a story for them.”

As it turns out, 1975 was the perfect time for the space habitat study to gain traction. “The whole culture and philosophy of society [in the 1970s] was that the future has no bounds,” Guidice says. This decade, which started just one year after the moon landing, was ripe with possibilities for getting people into space—and finding sustainable ways to keep them there. “The government was willing to participate in exploratory missions such as going to the moon, and so space settlements seemed to just follow as a possibility,” says Guidice. “Everybody was very optimistic about that at the time.”

Beyond optimism, O’Neill’s system designs could, in theory, actually be built. There were three different types of colonies (with population capacities ranging from 10,000 to over one million) that Guidice was asked to artistically interpret: toroidal colonies, bernal spheres, and cylindrical colonies. Aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun had conceived of the toroid wheel concept in 1952 but O’Neill’s main contribution, the bernal sphere, expanded on this proposed habitat. Since high radiation exposure was a strong possibility with the double cylinder wheel, O’Neill devised a round habitat for greater human protection. “Their studies showed that the configuration would be more ideal in isolating the population from radiation,” Guidice says of the bernal sphere.

Despite the plausibility of O’Neill’s calculations, he imagined future governments might view space exploration as mere frivolity. “I remember [him] saying a large government who has money like the United States would be able to fund such an incredible effort … but he said we’ve got to do it in the next 20 years, and that was 20 years ago,” Guidice says. O’Neill suggested that government resources at the turn of the 21st century would be tapped taking care of social issues for a larger population which would result in a lack of funding for future space settlement projects. “It turned out to be true,” Guidice says.

For Guidice, however, there’s still hope for space colonies. “There’s been a real renaissance of space exploration that’s been picked up by the private industry, which has given new hopes to settlements on the Moon and settlements on Mars and larger space stations,” Guidice says. Though renderings of future space habitats are now computerized and no longer hand-drawn, the influence of hyper-modern illustrations like Guidice’s still exist as mainstream media’s idea of what the future looks like. From science-fiction movies to animated alternate universes, the same visual tropes of what space habitation looks like persist. “It’s kind of neat how its become common culture,” Guidice says. Forty-three years later, excitement over imagining a life in space still resonates.

*Correction: We originally referred to “several hours” of research and revision. It took a lot longer than that.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook