The Moon Went on Tour Through England

It dangled over church pews and disco dancers in Dorset.

In July 2019, as we Earthlings commemorated the 50th anniversary of our maiden moonwalk, we craned our heads back to greet our luminous, mottled satellite 239,000 miles away. The Moon is our constant companion, but decades after the Eagle lander touched down in the Sea of Tranquility, and long after NASA shared images of those crisp, furrowed bootprints in the lunar soil, it’s still sometimes hard to look up at our bright neighbor—so close, and so far—and imagine being there.

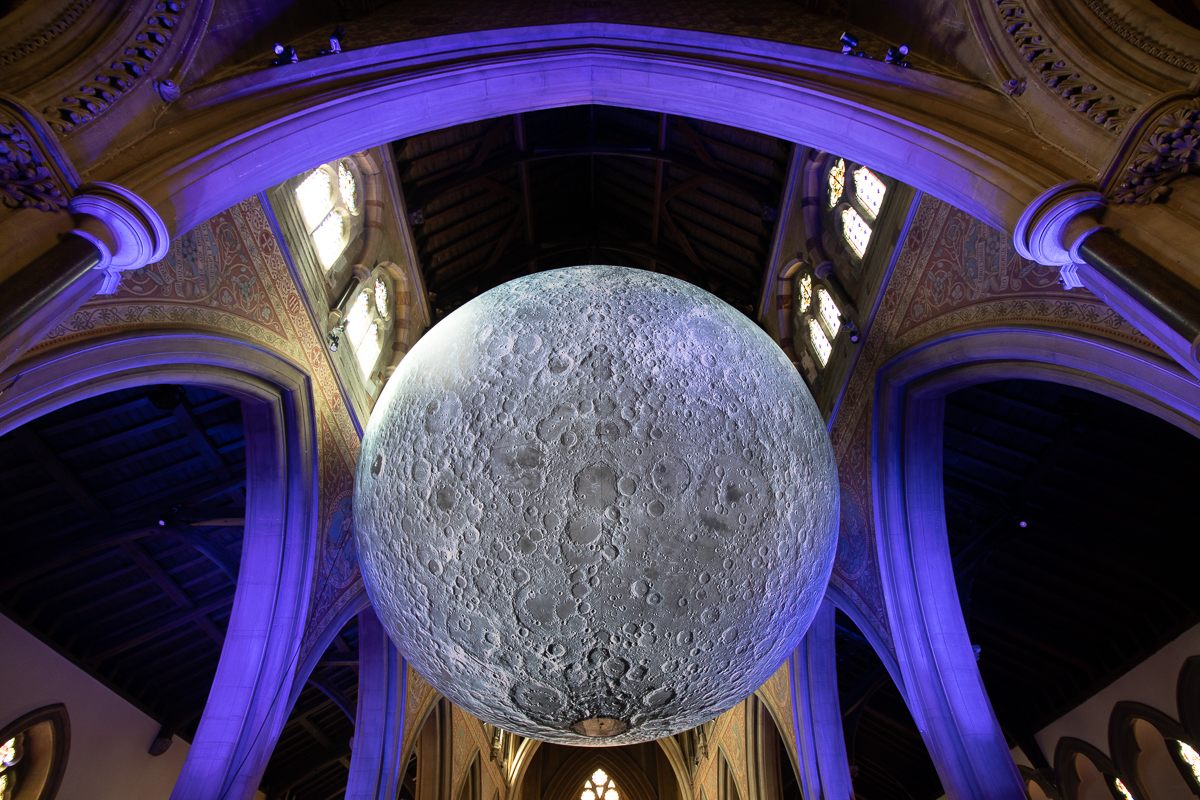

In the last few weeks, people in Dorset, England, didn’t have to picture going to the Moon: It came to them—huge, bright, nearly close enough to touch.

Since 2016, this moon—an art installation by British artist Luke Jerram titled Museum of the Moon—has traveled the world. Denmark, France, Belgium, Beijing, Ireland, Latvia, Spain, Austria—they’ve all gotten a glimpse. Our planet has a single moon, but Jerram has several installations in circulation. Sometimes the 308-pound, helium-filled balloons are suspended over pools or other water, so that the glow spills across the surface. When they hang indoors, venues often dim the lights, conjuring a night sky. Visitors sometimes lie on their backs, as if they’re sprawling on the grass or night-cooled sand, gazing up.

In June and July, one of Jerram’s moons hung below stained glass at St. Peter’s Church in Bournemouth, soared above pews in Sherborne Abbey, and floated over the neon-lit bodies of dancers at a silent disco inside the Nothe Fort, a 19th-century military structure in Weymouth—all part of the Dorset Moon extravaganza.

At each stop on the Museum of the Moon’s tour, musicians and visual artists performed or installed work beneath the moon—from a “starlit” walk through a dome designed to look like the Apollo 11 lunar module to an audience-assisted performance, where people stomped charcoal into a fine dust, leaped across a canvas, and pledged to reduce their carbon footprints here on Earth.

Jerram began dreaming of an exhibition like this more than 15 years ago, when he was biking to and from work in Bristol. Whenever his route sent him whizzing across bridges, Jerram took notice of the shoreline, swallowed and revealed by high and low tides. The nearby Bristol Channel has one of the largest tidal ranges in the world, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with several spots where the difference between high tide and low tide is close to 30 feet, or more.

As he passed the rising and falling water, Jerram found himself thinking about the Moon’s gravitational pull—literally, on the water, but also more symbolically, as a force tugging our eyes, imaginations, and ambitions skyward.

The project finally took root in 2016, when Jerram drew on high-resolution NASA imagery of the Moon’s surface, captured by instruments aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Jerram’s versions are on a 1:500,000 scale. His moons measure 22 feet in diameter, with each centimeter corresponding to a little more than three miles of the lunar surface.

Still, the project takes some artistic liberties: Unlike our Moon—which appears to glow only because it reflects sunlight—these moons are illuminated from the inside. It’s also accompanied by an atmospheric soundtrack by composer and sound designer Dan Jones (though actual lunar residents wouldn’t hear much of anything).

After Dorset, Jerram’s moon hopped across the Atlantic, stopping in Providence and San Francisco, where it’s on view at the Exploratorium through September 2, 2019. It’s landing in Milwaukee from August 9-11, 2019.

It certainly draws crowds: Some 41,000 visitors turned out on the moon’s jaunt across Dorset. That might be because, while we can press our eyes to telescopes or zoom in on our computers to hover over craters or long-dormant volcanoes, most of us will never get close to the real thing—so familiar and still utterly alien. Jerram envisions his creation as “the most intimate, personal, and closest encounter” most visitors will ever have with our cosmic neighbor.

Meanwhile, his artwork’s rocky kin is up there in the sky, night after night, full of familiar pockmarks to revisit—or features to notice for the very first time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook