You Can Own Moon Dust Collected by Neil Armstrong

NASA accidentally sold it, tried to take it back, lost it in a court battle—and now you can own it.

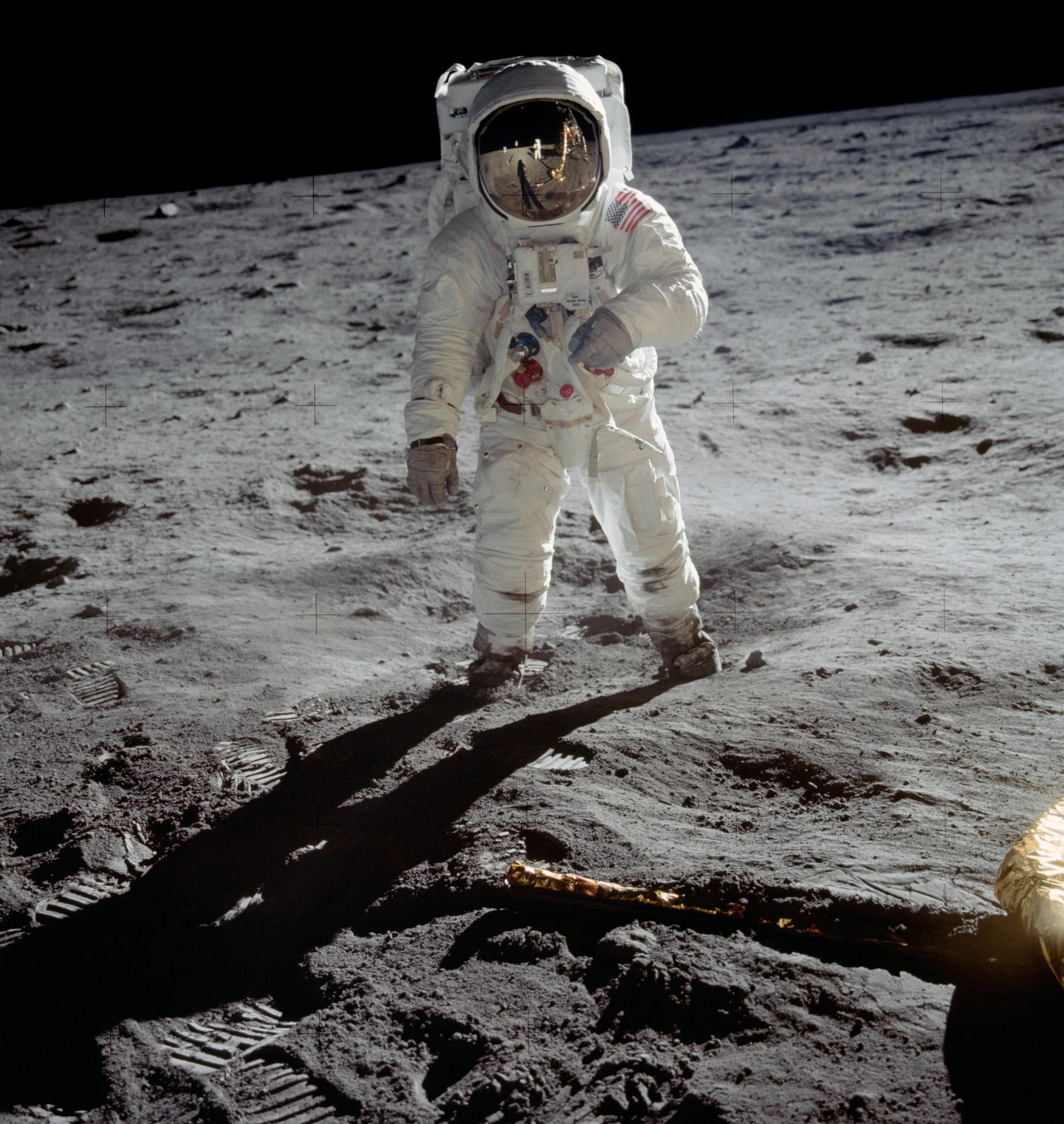

The first thing Neil Armstrong did after setting foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, was defy orders. The entire point of the Apollo 11 mission was to collect lunar material. Mike Mallory, a member of the Apollo 11 Navy frogman recovery team, remembers being instructed to “save the moon rocks first. We only have one bag of rocks. We have lots of astronauts.” But seven minutes after stepping onto the moon, Armstrong was busy taking panoramic photos. “Neil, this is Houston. Did you copy about the contingency sample? Over.” Armstrong replied, “Roger. I’m going to get to that just as soon as I finish these…[this] picture series.” Eight minutes in, Armstrong finally got around to collecting the first sample, known as the “contingency,” a failsafe to ensure the mission got their moon rocks even if they needed to make a quick exit.

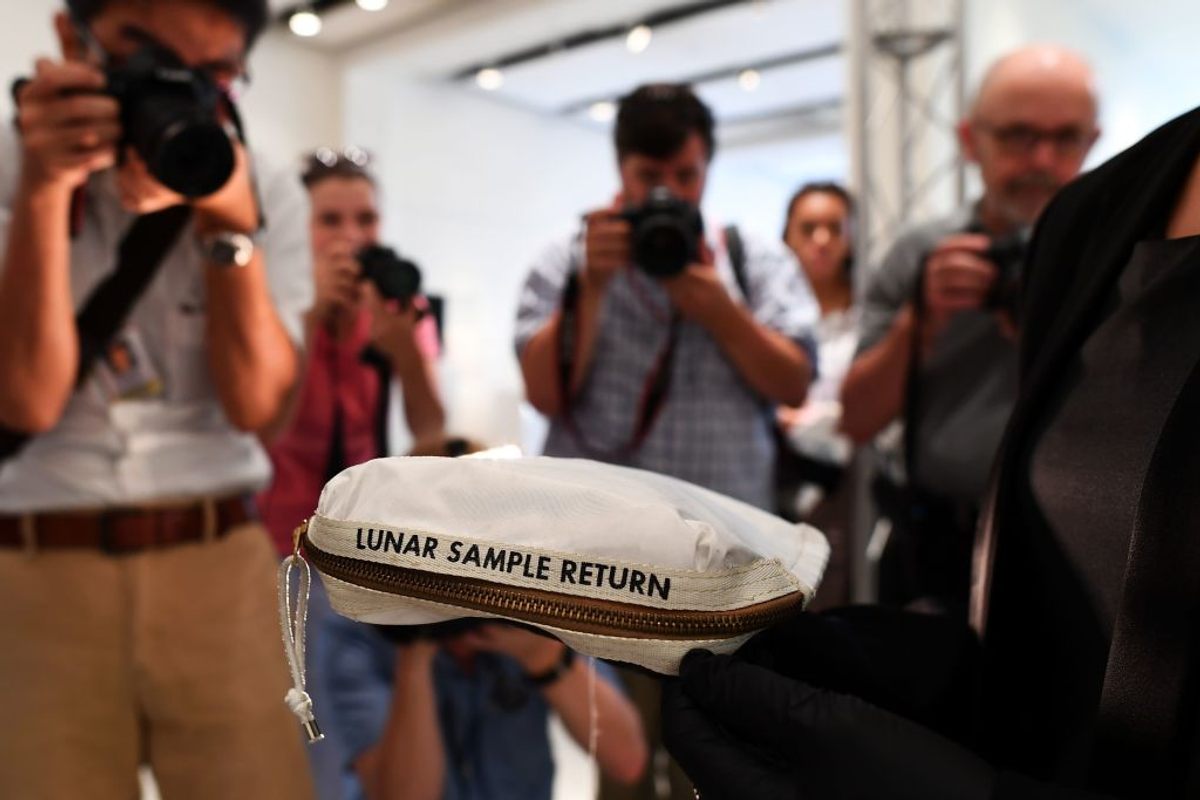

More than 50 years later, Bonhams auctioned off a small amount of the lunar material Armstrong collected. Due to a strange history that includes mislabeling, a U.S. Marshal sale, and a years-long court case, this is the only lunar dust collected from any Apollo mission that can be legally sold at auction. That, plus this sample’s connection to Armstrong and the Apollo 11 mission, is what makes these tiny specks of lunar dust so valuable. “I think one of the keys for this is that it’s from the contingency sample. So it’s the very first dust [collected] and it’s collected by Neil Armstrong who’s like, you know, he’s the guy,” says Adam Stackhouse, Bonhams’s senior specialist in science and technology.

Armstrong and fellow astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin Jr. collected a total of 47 pounds of lunar material while exploring the moon’s surface. And NASA carefully labeled and stored every ounce of it, except for trace amounts trapped in the Beta cloth contingency bag, which protected a Teflon bag Armstrong used to scoop up the majority of that two-pound contingency sample. Somehow the cloth bag used to collect the very first lunar material Armstrong retrieved was misattributed to the Apollo 17 mission which took place three years later—though that mission didn’t even have such a bag on board. Then NASA sold the mislabeled cloth bag sometime toward the end of the Apollo program in 1975, not knowing some precious lunar dust still clung to its lining.

The contingency bag had already changed hands several times by the time Max Ary, the then-president of the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center, acquired it. Then in November 2003, news broke that more than 100 of the Cosmosphere’s artifacts were missing. Ary, it seems, had been “playing a little fast and loose with, you know, which items were in his collection and which items were part of the museum collection,” says Stackhouse. The lunar dust was not among the missing artifact, but when Ary was sentenced to three years in prison for the stealing and selling of museum artifacts in 2015, objects from Ary’s personal collection, including the contingency bag, went up for auction in a U.S. Marshal sale to help pay for court-ordered restitution.

Enter Nancy Lee Carlson, a Chicago-based lawyer fascinated by the Apollo missions. In February 2015, she came across the strange Beta cloth bag on a federal auction website. She put down an offer of $995, won, and stuck the bag in her bedroom closet. A collector, Carlson had a hunch the bag was used during an earlier Apollo mission. So she sent the bag to NASA for verification.

NASA planetary mineralogist Roy Christoffersen tested the bag. Using sticky carbon tape, trace amounts of lunar dust were pulled from the inside lining of the cloth bag and then placed onto six aluminum cylinders. NASA even cut the bag to ensure they got all the lunar material off the bag. They tested the sample, determined it matched others from the Apollo 11 contingency bag that had remained in NASA’s possession, and decided not to send this sample back to Carlson. There was just one problem: that wasn’t their dust.

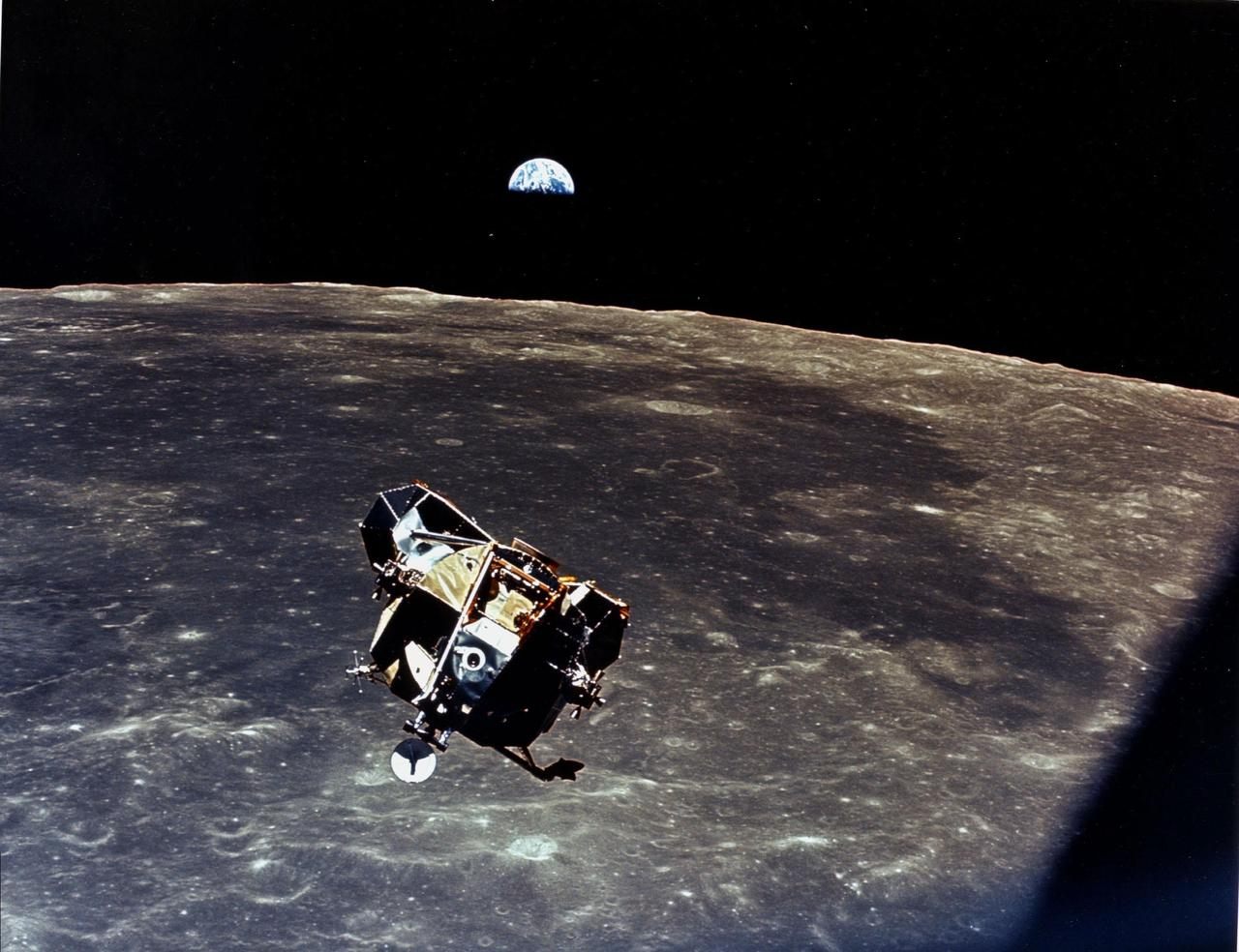

Carlson and NASA went to court. NASA argued the artifact “belongs to the American people,” reported the Chicago Tribune. But the judge ultimately sided with Carlson. The government had after all sold the bag, with its trace amounts of lunar dust still inside, twice. The bag was returned to Carlson. Soon after that in 2017, she put it up for auction. Cleaned of any lunar dust, the bag sold for $1.8 million—more money than any other U.S. space mission artifact has ever fetched. And now the lunar dust collected from the bag, which NASA returned to Carlson only recently, could sell for even more.

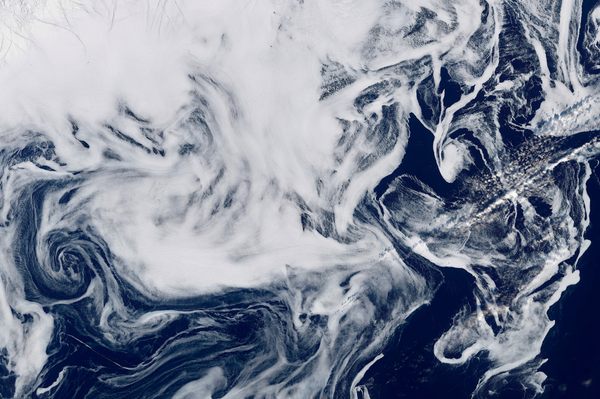

Stackhouse was careful to verify the lunar dust again, recruiting the help of geochemist Stephen Mojzsis from Budapest’s Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences. Mojzsis tested each sample using an electron microscope, which emits different energies based on the substance the electrons encounter. “What I’m doing when I analyze these samples is I look for elements such as nickel and chromium and iron and titanium, all of which are particularly enriched in lunar samples,” explains Mojzsis. The moon and the Earth are essentially made of the same stuff, says Mojzsis. That’s because “the consensus view is that the moon formed from the earth via a giant collision during the early stages of planet formation.” But because the moon doesn’t have an atmosphere to shift things around, the elements on its surface are very, very old, says Mojzsis. Aside from the occasional meteorite strike, things don’t really change a lot on the moon.

To date, only one other sample of lunar material has ever gone to auction. In November 2018, a Sotheby’s auction of three “moon rocks” sold for $855,000. The tiny rocks (the largest was less than a square inch) were collected in 1970 during an unmanned Soviet mission to the moon. While few people know of the Soviet Luna-16 mission, most have heard of the Apollo 11 mission. “Apollo 11 was a worldwide event,” says Stackhouse. “That’s one of the key things that struck me. It was something that everybody, even the Soviets, couldn’t help but congratulate the U.S. [on].”

As Armstrong collected the contingency sample in July 1969, Buzz Aldrin looked on. He told his commander, “That looks beautiful from here, Neil.” As Armstrong tucked the sample safely in his left thigh pocket, he took in the strange lunar vista. “It has a stark beauty all its own,” he replied. And these six tiny cylinders of lunar dust, an artifact of perhaps humankind’s greatest achievement, can be yours—that is, if you have an extra $1 million lying around somewhere.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook