Creating Art to Capture Memories Before They Fade

On the final days of “The Fellowship of Highway 95,” Lindsey Rickert and Francesca Berrini process what they experienced in Nevada.

Time was top of mind as Francesca Berrini and Lindsey Rickert began the final days of their journey on “The Fellowship of Highway 95,” a week-long artistic adventure from Las Vegas to Reno up Nevada’s “Free-Range Art Highway” organized by Atlas Obscura and TravelNevada. They were looking ahead to the second phase of their project, which would take place entirely within a studio. But before the trip was done, they had several more stops to make.

In continuation of the previous days’ journey into the mythical “unknown,” the women headed to Walker Lake to catch a glimpse of Cecil the Serpent, the elusive sea monster said to reside in the lake.

It’s clear that Cecil holds a privileged place in the town of Hawthorne’s lore. Chatting with locals, the artists learned that it’s a tradition to take marshmallows down to Walker Lake’s shores with the hopes of coaxing the creature from the waters’ depths. Hawthorne’s unofficial mascot also makes appearances several times per year during parades, when he slithers through town blowing smoke through his nose.

In town, they stumbled upon the very float itself, stored in an open-air garage and visible from the road.

“We may not have spotted Cecil…but he has definitely still inspired our work,” Rickert wrote in day five’s travel journal.

Contemplating Cecil and the dwindling time left on their trip, Berrini and Rickert mused on Nevada’s cosmic scale. Observing the mountains that surrounded them, they thought of Lake Lahontan, the Pleistocene body of water that once covered a good portion of the state. Sea monsters did, in fact, once swim through this desert.

Nevada’s official state fossil is the ichthyosaur, and it holds the largest concentration of these creatures ever discovered. Growing up to 50 feet long, the massive marine reptiles swam through the Great Nevada Basin 250 million years ago.

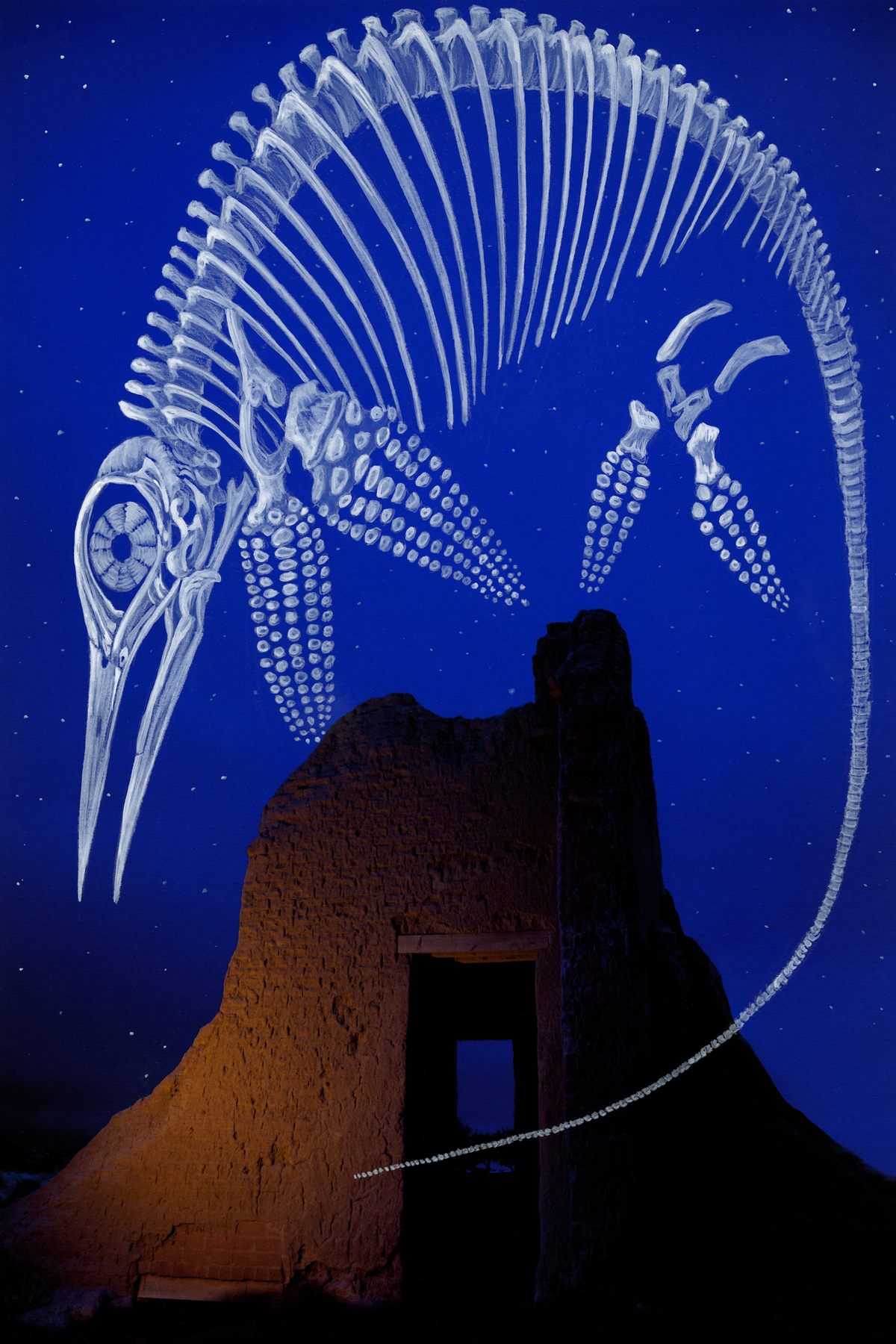

Using day-for-night lighting, Rickert took a photograph of the ruins of Fort Churchill, a state park housing the remains of a U.S. Army fort and a Pony Express station. Berrini then hand-drew the ichthyosaur on Rickert’s royal blue sky like a constellation, hovering above and beyond Nevada’s past, present, and future.

“At times it feels like we have been on the road for a month and others, it seems like just yesterday,” Rickert wrote the same day.

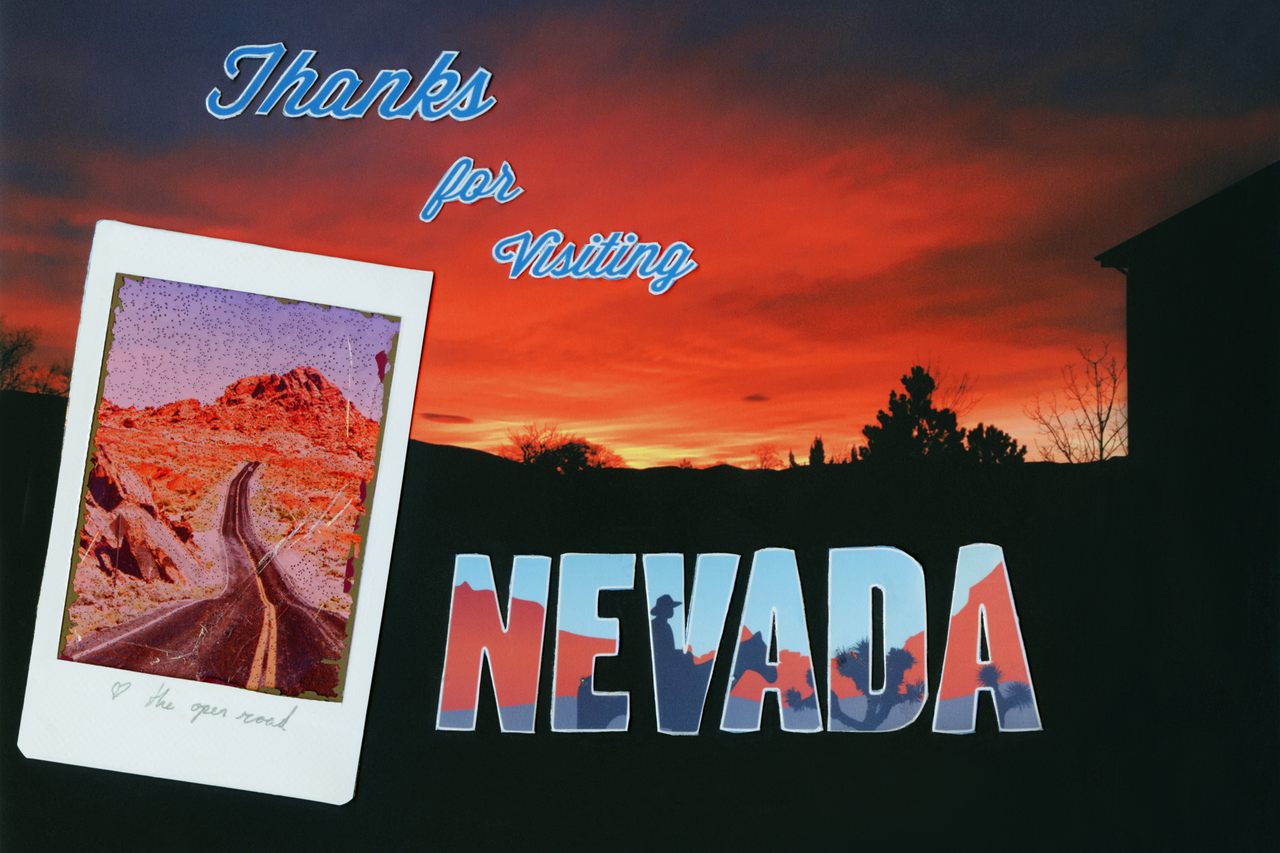

Arriving in Fernley near the end of the trip, Rickert snapped a picture of a fiery sunset.

“The sky was so captivating when we arrived at the hotel that we stopped unloading our luggage from the van, left most of the doors open and sprinted to the side of the hotel to take some photographs and marvel in its beauty,” Rickert wrote. “I later asked the front desk employee [if] this was a common sunset and she laughed and told me yes.”

Like most of the other postcards in their series, Thanks for Visiting (featured at the top of this page) combines elements from different days of their journey. The background horizon is a photograph of the sunset in Fernley. The polaroid was a blank one Berrini found in the desert on the very first day, near Seven Magic Mountains. The text came from pictures of a sign outside Rhyolite.

“This one felt like a perfect way to close out the trip,” Rickert wrote of Thanks for Visiting. More than any other work in the series, it resembles a traditional postcard.

Mentally and physically exhausted upon returning home, the two artists’ days on Highway 95 swirled in their brains. Rickert’s photographs were indispensable in helping Berrini sort her memories into a loose narrative.

“Collage is a way to revisit and process,” Berrini says. “It made [the trip] more linear in my memory because we were going through the images day by day.”

Created in the trip’s aftermath using materials collected from each day of the journey, the body of work doesn’t follow a linear trajectory. Instead, it offers a holistic reflection upon the Fellowship as a whole, its aftermath, and its lingering effects.

In what is perhaps the most ambitious artwork to come out of their endeavor, Berrini juxtaposes a photo of herself, shot by Rickert from a distance, with what appears to be a map of Nevada and Highway 95’s route through the state.

Upon closer inspection, it’s clear that this was once a map of the area, but now it’s something new: fiction that is factual in the sense that it’s true to Berrini and Rickert’s experience. Beginning with a map of Nevada and Highway 95, Berrini disassembled the piece and rearranged it into a semi-fanciful landscape. Its mind-boggling detail both engages and disorients, capturing the delirium that always seems to come after a transformative journey.

On a grander level, this artwork is an uncanny portrayal of Nevada, a state where time, terrain, history, and myth co-exist harmoniously.

This post is promoted in partnership with Travel Nevada. Head here to get started on your adventure.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook