New York City’s Pigeons, Like You’ve Never Seen Them Before

They’re ready for their close-up.

If you sit on a bench in a New York City park, perhaps with a snack, you are likely to have feathered company. They may emit a soft, gurgling coo as they bob around your feet, waiting for a drop. If you’re like most people, you’re much more likely to try to shoo them away than you are to pause and admire the ubiquitous pigeon. But photographer Andrew Garn isn’t like most people.

“Watch a flock of pigeons in your local park or sidewalk—at first impression you might think they were all alike,” he says. “But if one were to observe for a few minutes, you would not only note the startling range of feather patterns, but behavioral diversity as well.”

Like many New Yorkers, Garn started out ignoring pigeons. But thanks to a visit to a pigeon coop years ago, he’s become an unexpected flag bearer. His new book, The New York Pigeon: Behind the Feathers, showcases their overlooked beauty in a series of sometimes humorous, sometimes startling images.

As part of this project, Garn photographed the birds both on the streets and in a studio. These avian portraits were arranged through Wild Bird Fund, a rehabilitation center, and each of his sitters had its own story. Fido, for example, was found, starving, under an elevated train in Queens. Apollo, a pale gray pigeon treated at the center, now lives outside its headquarters. And Jana came in with torticollis (neck twisted to one side), likely caused by lead poisoning. In her portrait she is captured while flying gracefully through the frame.

Atlas Obscura talked to Garn about why pigeons get overlooked, their innate intelligence, and how it’s possible to appreciate nature even in one of the world’s most populous cities.

Tell us a little about how this project began.

As I grew up in Manhattan, I actually never really noticed pigeons. I saw them, but never genuinely looked at them. In late 2007, pigeons came to mind when I was searching for a new, underexplored photography project. Under-recognized topics have been a consistent theme in my work over the years—I have documented U.S. penal architecture, Stalin-era industrial plants built with forced labor, the Las Vegas homeless, and 42nd Street/Times Square, pre-Disney.

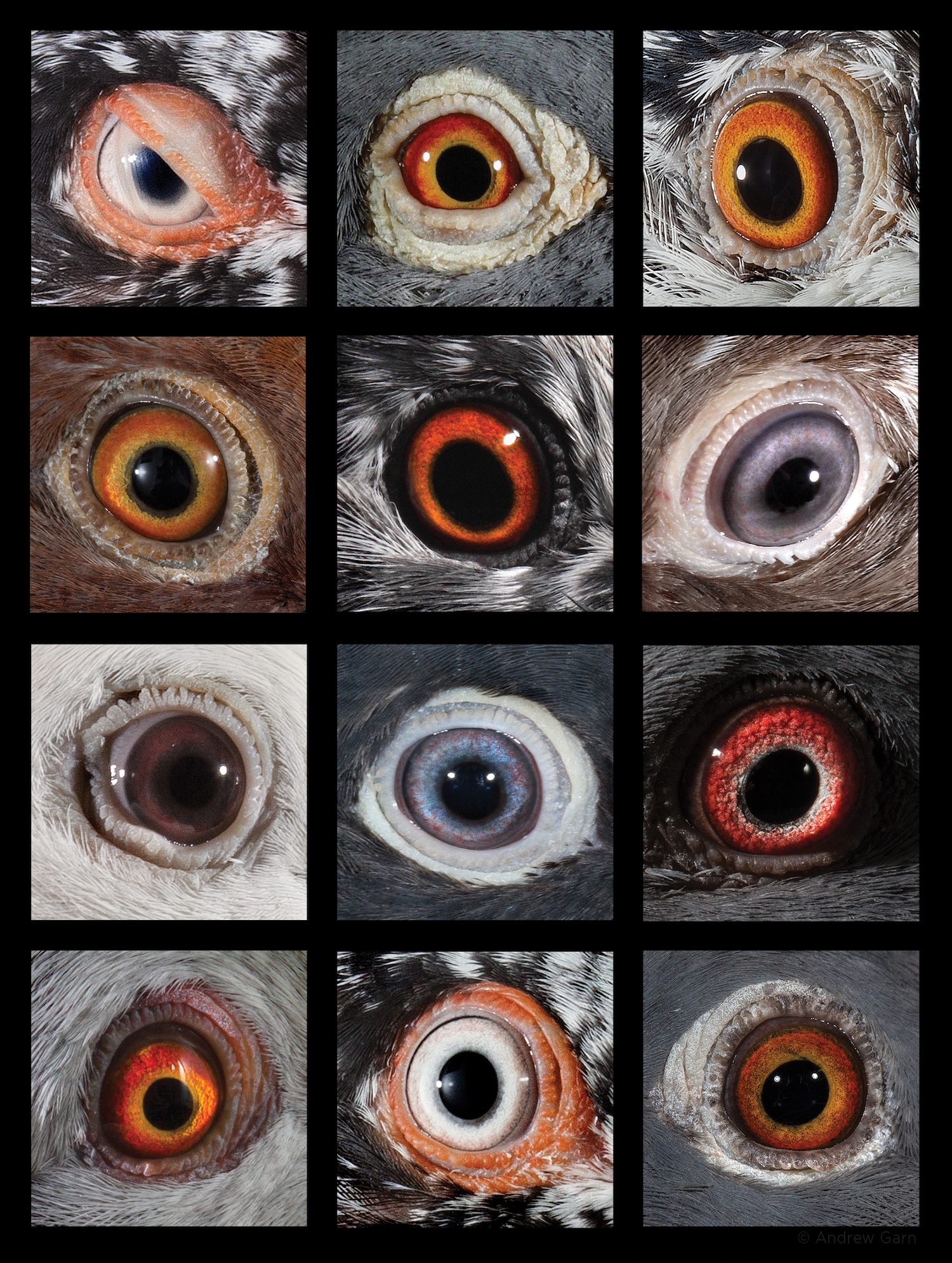

Pigeons seemed to fit the mold perfectly, so I visited a coop where I was able to get close to pigeons for the first time. I was immediately mesmerized by the iridescence, the color variations, and the eyes. As I began photographing the birds, I saw them as these incredibly precious objects. What truly astonished me was capturing their midair flight in a makeshift studio. Here before me was this beautiful, delicate feathered entity that could fly in dazzling, acrobatic configurations.

It became a very long a commitment, around 10 years, one of those projects that took on a life of its own. As I got more involved, more layers of pigeon culture became apparent and I became part of a larger pigeon community.

How did you produce the studio portraits?

My first shoot was in a pigeon coop, then I moved to the street using a makeshift studio in a box. It was very difficult to control lighting, and to catch pigeons, so I decided to bring my lighting and camera to where the pigeons were. In 2012, the Wild Bird Fund opened its doors, and I contacted the director Rita McMahon about photographing some of the convalescing pigeons. Coincidentally, she had seen an art exhibit I did on pigeons that included photographs, video, and live pigeons, so she knew of my work and welcomed me to visit.

What are pigeons like as subjects?

In the studio, I have observed certain attitudes from pigeons—some, like Apollo, are very sweet and compliant, while others more aggressive, attempting to establish a dominance over the photographer, like the cover pigeon, Dr. Brown. There are many similarities with photographing humans actually. I am striving to get personality from pigeons, so it’s a matter of waiting for that moment or pose.

Many times I will focus on the head and neck—the eyes and iridescent chest feathers are especially beautiful, but I also capture wing patterns or the overall pigeon.

Did you discover anything surprising about pigeons while you worked on this project?

The history of the human-pigeon relationship is deeply faceted. In fact, pigeons were the first domesticated bird. There are dovecote ruins in Masada (Israel) and Petra (Jordan). About 5,000 years ago, Egyptians started building multistory pigeon houses to keep them for food, but also, most importantly, for their guano—the Nile Valley was first fertilized by pigeon poop.

Pigeons have been used as messengers since perhaps the time of Noah, who is said to have used a pigeon to search for land after the floodwater receded. The Romans used pigeons to broadcast the results of chariot races. Genghis Khan established a pigeon post system throughout Asia and Eastern Europe. Pigeons were integral to warfare in World War I—both the Germans and British used pigeons for surveillance and to carry messages across enemy lines.

And because of their keen vision and intelligence, pigeons have been used in numerous experiments on missile guidance and cognitive behavior modification.

What do you say to New Yorkers who dismiss pigeons as a nuisance?

For many New Yorkers, the only wildlife we get to see are squirrels or pigeons. I suspect that these common animals can become the “gateway drug” to nature for many city dwellers. This theory is backed by the university study called “The Pigeon Paradox,” which posits that pigeons are the only real nature people in cities are exposed to, and how important that is to the appreciation and enjoyment of natural world in general.

I am always amazed at the broad diversity of people feeding pigeons in my local park—from high school students to older pensioners. Through exhibitions of my photographs and other presentations, I have happily converted many people to the world of pigeon appreciation. Many people have told me, unsolicited, that “I never liked pigeons, but now that I have seen your photos, I have a newfound appreciation for them.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook