The New Zealand Birdwatchers Who Fly to North Korea in the Spring

The quest for a bird that continues to defy international sanctions.

The sky above North Korea is quiet. U.S. airlines are prohibited from flying over the country and almost all other national airlines avoid it. But every spring, around 110,000 bar-tailed godwits fill the firmament. These migratory wading birds are on an annual journey of more than 11,000 miles, from New Zealand to Alaska, and stop to refuel at the two-thirds mark, on the North Korean coast by the Yellow Sea. They are joined in the sky by Air Koryo flights—five a week—from Beijing to Pyongyang. In 2009, and then in 2016, a small group of New Zealand birdwatchers was on one of these flights, on a mission to survey, count, and observe the godwits on their six-week stopover on the mudflats of the hermit kingdom.

Adrian Riegen lives in the distant western suburbs of Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city, in the foothills of the jungly Waitakere ranges, where white-ruffed tui croon and crackle among native kauri trees. Since the 1980s, he has volunteered with the Pukorokoro Miranda Naturalists Trust. Around the Firth of Thames, about 80 minutes from Riegen’s home, the conservation organization bands shorebirds’ legs with coded, colored strips of plastic or metal that allow watchers across the globe to track their migration routes, nesting sites, and wintering grounds.

New Zealanders, on the whole, are unusually interested in birds. The country is home to some 378 species, many of which cannot be found anywhere else in the world. There’s the kea, a large alpine parrot, a glossy olive green, with brilliant orange feathers under its wings and a dangerously sharp beak. Its cousin, the kakapo, trots sweetly along the forest floor, its flightless wings billowing behind it like the gown of an Oxford don. The tiny black robin, colored like the country’s sports teams, hovers on the brink of extinction. Like a rugby player’s nose, the beak of the wrybill skews to one side. Kiwi are iconic, morepork are adorable, and bellbirds have the most beautiful songs.

New Zealanders treasure their birds, says Riegen, because they constitute almost all of the country’s fauna. “We don’t have the animals that other people have,” he says. “Africa’s got all its big mammals, all that sort of thing—here, we only have birds.” By contrast, New Zealand’s only native land mammals are three small species of bat. But dun-colored shorebirds, such as the bar-tailed godwit, lack the allure of “the quirky ones, the keas, kakapo, things like that,” says Riegen.

Much of the Trust’s work focuses on these ostensibly unglamorous waders. Godwits have long spindly beaks, stubby legs for a wader, and a russet breast that fades to grey in the cold. In early September each year, they land in New Zealand, just in time for the thaw. They will gorge themselves on mollusks, crustaceans, and worms, so that by the time they leave in mid-March, they weigh up to 70 percent more than when they arrived. Their bodies change to accommodate the fuel they will need for their migration. More than half of their body mass is fat, natural steroids boost their flying muscles, and organs they will not need on the journey—gut, liver, kidneys—shrink to take up less space.

Unsolved mysteries about migratory birds—where they go and what they do when they leave New Zealand—have plagued birdwatchers there for some time. From the late 1980s on, Riegen and his fellow enthusiasts at the Trust have worked with countries around East Asia and Australasia to establish international organizations and personally track and band the birds themselves—from China to Australia to South Korea. In 2007 there was a breakthrough. For the first time, naturalists tracked a bar-tailed godwit on its migratory journey.

E7, as she was known, flew continuously for seven days. A transmitter inside her body revealed her location as she traveled through the East Asian–Australasian Flyway: over the Coral Sea, narrowly missing Guam, across the expanse of the North Pacific Ocean, to China, on the coast of the Yellow Sea that separates it from the Korean Peninsula. She had traveled well over 6,000 miles, without stopping once to eat, drink, or sleep. Later, she went on to Alaska. The return leg, in September, included an extra 1,000 miles: Alaska to New Zealand, direct.

The stop in the wetlands of the Yellow Sea is a critical opportunity to refuel. But increased industrialization in China and South Korea has left fewer and fewer places for the birds to stop. More than 10 percent of the world’s population lives within the river catchment area of the Yellow Sea, writes Riegen’s colleague Keith Woodley in his 2009 book Godwits: Long-Haul Champions. “They place huge demands on its freshwater resources, use its banks for garbage and sewage disposal, and engage in industries that pollute water and air with toxic wastes. But more significantly, they modify the very coastline itself with reclamations and other projects.”

In the last 50 years, two-thirds of Yellow Sea mudflats have disappeared, displaced by ports, factories, and other developments. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Riegen, Woodley, and other volunteers began surveying the Yellow Sea around South Korea and China, until all of the coastline—except for North Korea’s—had been documented at least once.

Working alongside the Yalu Jiang Nature Reserve in China, Riegen says, they could see birds heading across the Yalu River in their droves.* “We were watching birds flying into North Korea on the high tide, they’d fly across the river and we wondered how many more there were,” he remembers. From satellite imagery, the birders knew there were huge, undeveloped mudflats along the country’s coasts. “But there was nothing at all known about birds on North Korea’s coasts. If there was information, it hadn’t filtered out to the West.”

While South Korea’s and China’s coasts are increasingly lined with concrete, much of North Korea’s, thanks to four decades of isolation, remain as they have for centuries. Consequently, says University of Groningen ornithologist Jesse Conklin, “it seems likely that numbers of New Zealand godwits going to North Korea would be increasing proportionally, because mudflats are disappearing faster elsewhere,” though exact numbers remain unknown.

To complete their surveying, Riegen and his colleagues needed to get into North Korea, navigate its countryside, and reach its sensitive shores. “So we looked for a way to get into it,” Riegen says. “Not easy.” In recent years, North Korea and New Zealand have had little to do with one another, with the former under heavy international sanctions and the latter proudly, vehemently antinuclear. But historically, New Zealand’s relationship with one of the most isolated countries in the world has been less toxic than that of many of its allies. In the 1970s, the New Zealand–DPRK Society sprang up with the promise of fostering friendship between the two countries. The group was particularly helpful in the birdwatchers’ efforts, Reigen says. “We’re in touch with them all the time.”

North Koreans view New Zealand positively thanks to such efforts, says the group’s secretary, Peter Wilson. “Over the decades, a climate of mutual friendship, understanding and trust has developed.” Governments have come and gone, with some more accommodating to North Korea than others. Under Prime Minister Helen Clark’s left-wing Labour government, a New Zealand ambassador began to make annual visits, starting in 2001. These should not be misconstrued, Clark says. “During the presidency of George W. Bush, a lot of effort was made to address North Korean issues, and U.S. envoys visited there many times,” she says. “That is the context within which to view these events.” When the center-right National Party assumed power in 2008, the visits slowed and then ceased altogether.

For the last two years of Clark’s final term, Labour was in a coalition with New Zealand First, a populist party headed by veteran, if maverick, politician Winston Peters. In 2007, as Foreign Minister, Peters made a controversial, well-publicized two-day diplomatic visit to North Korea, just a year after the country’s first nuclear test. “And so, we thought this was an opportunity,” says Riegen. They explained to Peters what they had done in South Korea and China, and asked him to request permission to “go in there, and work with North Korean wildlife people, because there must be some, and survey their coastline, and see what we could find.

“And they said yes, and so that was our in,” Riegen Says. “That’s how it all happened.”

Two years later, in 2009, Riegen landed in Pyongyang, accompanied by fellow birders Woodley and David Melville. (In 2016, they were joined by another, Bruce Postill.) Riegen is bashful about the exact cost of the trips, much of which they cover themselves, conceding only that it is “quite a lot.” They were there for about a week, chosen years in advance to coincide with the biggest high tide. “When the tides are lower,” he says, “the birds stay out on the mudflats, in which case, you can’t count them and see what you’ve got.”

Their band—three or four bearded, birdwatching New Zealanders, and “about six” Koreans—piled into a minibus, bounced down dirt roads, through rural villages, and past lush rice paddies and farms. Workers stood out in the fields, planting potatoes, maize, and rice by hand. Everywhere they went, Riegen says, they saw people cycling or walking. And then, finally, they made it to the coast, where thousands of godwits were recovering from their long journey. Some had been banded by members of the group back in New Zealand, and would return to the precise spot, year after year.

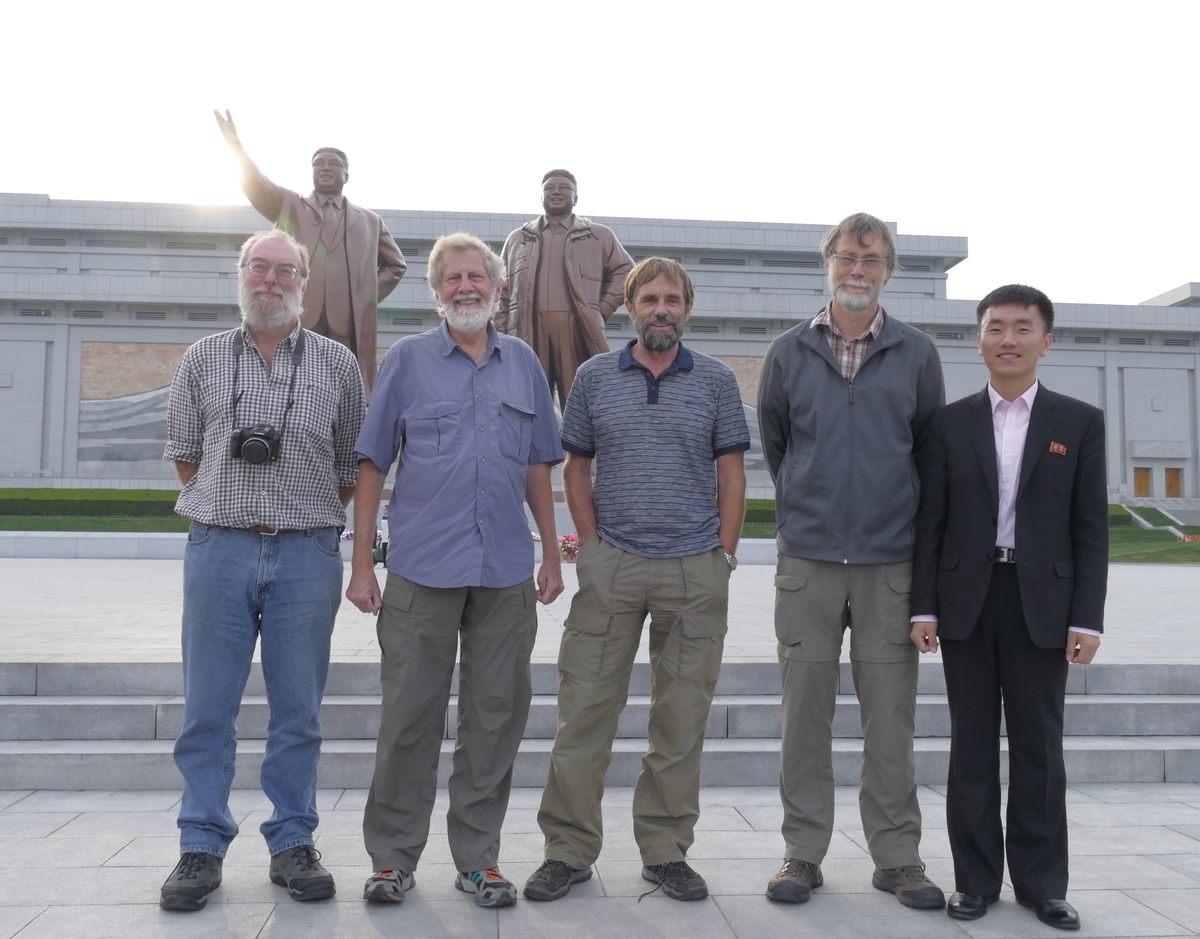

“The one thing with North Korea is that no one goes anywhere without a minder,” Riegen says. “You can’t go anywhere on your own. It’s just not acceptable.” Photographs show the New Zealanders in traditional birdwatching attire (think bucket hats, hiking boots, and sensible jackets) flanked by minders in suits. Wariness from the locals often gave way to curiosity, Riegen says. “If there were people around, we’d encourage them to come and have a look through our telescopes, and see what we’re looking at. Almost certainly none of them would have ever seen foreigners before in their lives.”

For the next week or so, the birders surveyed about 40 miles of coastline, returning each night to their approved hotel, where they ate ample meals of vegetables, potatoes, and rice, and coped with the vagaries of North Korean electricity. Sometimes, it was a five-hour round trip from their observation sites. “But, you know, that’s the way it is,” Riegen says. “So that’s what we do.”

The trips have provided unprecedented insight into the godwits’ migration patterns, but it is all far too late to slow the industrialization of the Chinese and South Korean coasts. “It’s easy for the governments in those countries to say, ‘Oh well, if we destroy this, the birds can go to another estuary,’” says Riegen. “But often that other estuary doesn’t have the food that these birds need.”

North Korea, for the time being, offers hope for the birds. “The Koreans—they feel like they’re really learning about it. And they want to be involved,” he adds. “They desperately now want to be involved in international conservation for these birds, and want to know what part they can play.” The birder team plans to return twice more, with funding from the New Zealand Department of Conservation helping with some of the costs.

North Korea’s precarious geopolitical position has proven a surprising blessing to the bar-tailed godwit (not unlike the variety of endangered species that call the Korean Demilitarized Zone home). And without the unlikely visit of a group of tenacious New Zealand birdwatchers, North Korean authorities might have remained unaware of the natural cargo that comes to their shores each year. “That’s what we’re doing it for,” says Riegen. “If we don’t use this opportunity to enlighten them and help them become part of the global flyway network, then we’re not doing what we should be doing. And that’s what it’s about.”

* Correction: This story was updated to reflect that the Yalu River separates North Korea from China, not South Korea.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook