Medieval Cathedral Spires Have Been at Risk From the Get Go

For centuries, they’ve been toppled by lightning, wind, and more.

Fire made quick work of the 300-foot spire that stood until recently atop Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral. As orange flames engulfed the lead-clad wood, smoke billowed skyward in thick, gray clouds. Sirens wailed, and so did onlookers’ voices. The blaze ate away at the spire until the structure leaned and then finally splintered and fell, like a tree trunk cleaved from its roots.

Cathedral spires often become key components of a city’s skyline, and that was the case with Notre Dame. Writing in The Atlantic after the spire collapsed on April 15, 2019, the journalist Sophie Gilbert called the cathedral’s top and towers “stately and certain in the springtime, as familiar as the sun.” Spires can serve as iconic architectural reference points, but that doesn’t mean they’ve had it easy.

Ever since they started soaring over towns, centuries ago, cathedral spires have had a rough go of it. Spindly and often fragile, they’ve suffered scores of indignities. Some have been rattled by wind, others battered by military assaults, pierced by lightning, or caked with guano. Notre Dame is no stranger to this fate. The cathedral’s first spire, which went up in the mid-13th century, was damaged and dismantled at the end of the 1700s, and the one that recently met a fiery end was a 19th-century replacement designed by the architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.

Some pointy towers began jutting up above European streets in the age of Charlemagne, but those were more like “wooden canopies—not quite exactly spires like we typically think of them,” says Robert Bork, an art historian at the University of Iowa who specializes in Gothic architecture. (Bork’s friends call him Spire-Man, on account of his abiding love for—and rigorous scholarly consideration of—all things peaked and soaring.) The stereotypical spire, which Bork calls “a tall, pyramid-shaped hat,” really began crowning cathedrals in France in the middle of the 12th century, just as Gothic architecture became the style du jour.

Symbolically, Bork says, spires emphasized the relationship between the heavens and Earth. They also functioned like an arrow pointing to holy ground (Notre Dame’s spire was even known as la flèche or, “the arrow”). Spires draw attention to a church from a distance. A triangular topper “does visually what the bells do sonically,” Bork adds. “Bells called out to people’s ears, but the spire called to your eyes.”

In the late Middle Ages, Bork says, a spire was also essentially “a barometer of what the social conditions [were],” and residents’ sentiment toward the church. If the church was a respected civic monument, public funds were sometimes funneled toward a big, fancy, spire; puny spires tended to rise above places where locals weren’t so keen on the clergy. The 466-foot spire at the 15th-century Strasbourg Cathedral in Alsace, France—which Bork characterizes as a “crazy-ambitious tower”—had ample funding because the church “had basically been co-opted by the town government.” Afterwards, Bork adds, “the families started feeling like the church really belonged to them. We have a big donation book where you can see who gave how much money on which day and their records. You know, ‘widow-so-and-so gave the whole family fortune to the cathedral-building project.’” And since spires are built from the bottom up, “you can read the tower almost like you read growth rings in a tree,” Bork says. “If they succeed in building all in one go, then you know the money is flowing and the social purpose is unified.”

At Strasbourg, the result is a spire with skeletal, winding staircases, gang planks, and switchbacks. “It’s just completely insane,” Bork says. “It doesn’t look like it should stand up, and it wouldn’t stand up if it weren’t held together with iron reinforcements.”

Many spires were the tallest structures in the towns they rose above, and they were sometimes outfitted with belfries, lookouts, or other design elements that made them a type of community infrastructure. The bells might toll to herald a religious service, or to tell townspeople that it was time to head to the market, or return home. Several examples across France, England, and the Baltic region soared hundreds of feet, Bork adds, setting “a class for height that really wasn’t exceeded until the Eiffel Tower.”

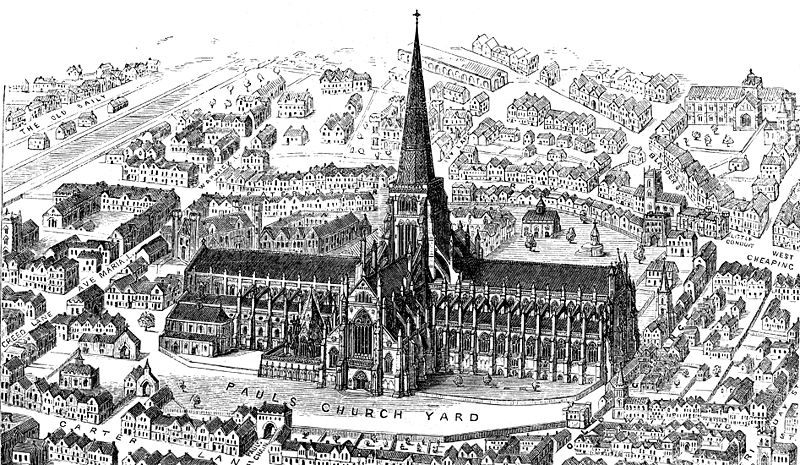

The Strasbourg spire is the tallest medieval example that still stands. Meanwhile, several of its immense contemporaries eventually met spectacular ends. Lightning spelled the death of the wooden spire on top of Old Saint Paul’s, in London. Centuries later, the English historian William Benham would recount that the fire caused the spire’s lead coating to pour “down like lava upon the roof.” Lighting also defeated spires on Saint Mary’s church in Stralsund, Germany; and Saint Olaf’s in Tallinn, Estonia. Over the years, several spires on France’s Rouen Cathedral were lost to gusts and sparks. The spire on the cathedral in Lincoln, England, blew down in a 16th-century storm, and a storm also felled the one on Saint Elizabeth’s church in Wrocław, Poland. The wooden spire on the top of the cathedral in Beauvais, France, was a victim of poor engineering and a time crunch, Bork notes—it collapsed of its own accord in 1573, just a few years after it was built, because its supports buckled before anyone could fix them.

Stone spires have weathered the centuries a little better than the flimsier wood ones, Bork says, but they’re not totally safe, either. “The stone ones are heavy, and so they put stress on the foundations and sometimes they sink and sometimes they crack.”

Notre Dame will eventually be rebuilt. Restoration proposals and funds are already pouring in. When renovations get underway, crews will face a conundrum familiar to conservators and art historians the world over: How do you balance a fidelity to an object’s past while girding it for the future? In “a perfect world,” Bork says, it “might be nice to try to put all of that [wood] back,” but restoring the whole roof would require a whole lot of oak. “Some people really want you to say, ‘It’s got to be the original material exactly, because we want the precise archaeological truth,’” Bork says. There’s a loveliness to that, he thinks, but given the circumstances, he believes it would be reasonable to use modern, durable material inside, and cover the outside with a metal sheathing that evokes what was lost. With the right covering, he says, passersby might find the replacement “indistinguishable” from its dearly departed predecessor—and hopefully the new one will soar over the city for centuries to come.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook