Object of Intrigue: The Dummy Paratroopers of WWII

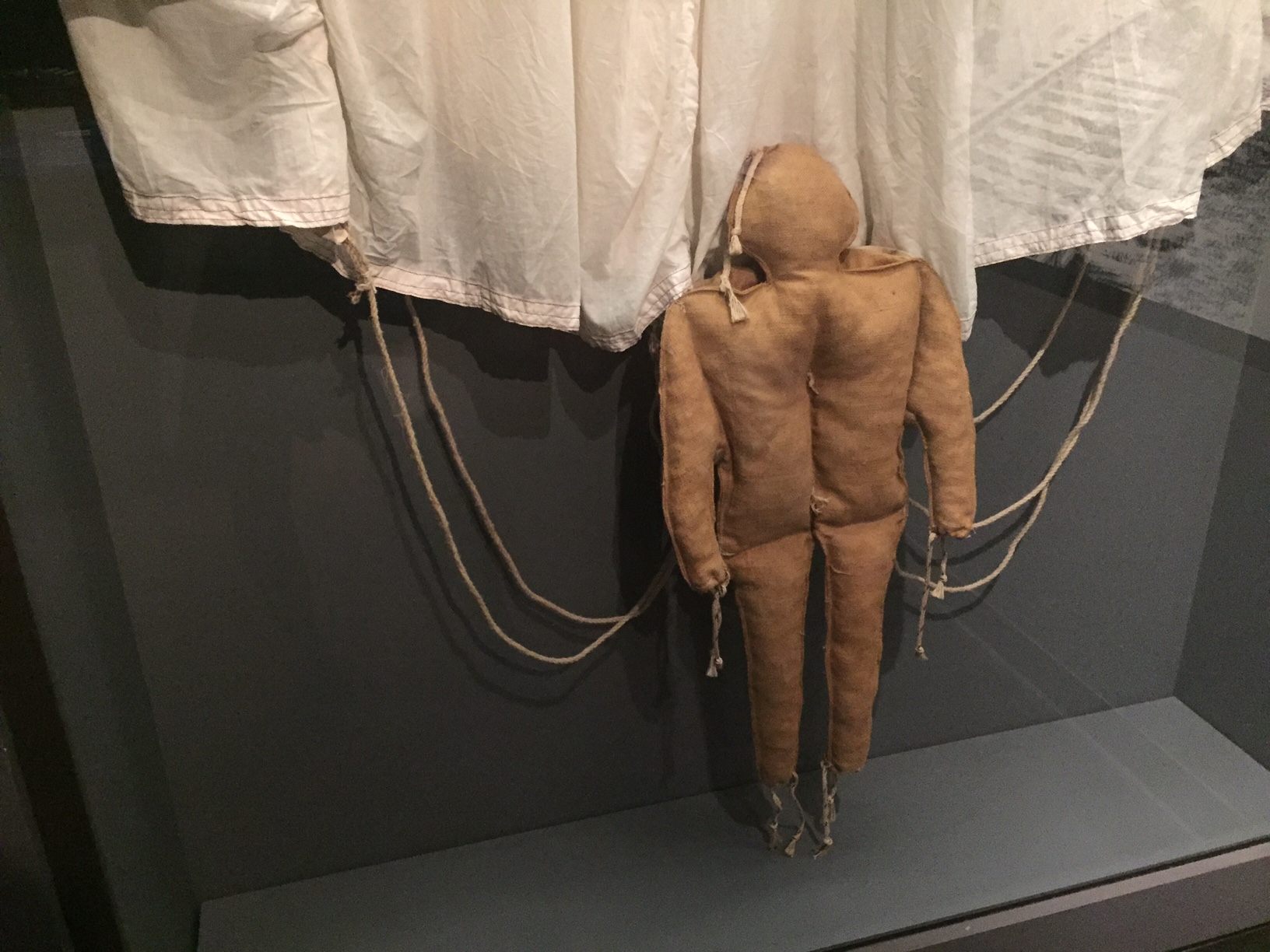

A “Rupert” dummy paratrooper at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans. (Photo: Ella Morton)

In the hours before sunrise on D-Day, June 6, 1944, Allied soldiers sat bundled on ships and strapped into planes off the coast of Normandy, waiting for the signal to storm the beaches of German-occupied France and change the course of the war. Further east, however, D-Day operations had already begun–with a dummy drop.

In order to give the Allied invasion fleet the best chance at victory on the beaches of Normandy, German forces needed to be distracted and directed away from the invasion site. To do so, they came up with Operation Titanic, a plan in which hundreds of dummy paratroopers were dropped many miles east of the site to lure German firepower.

The dummy paratroopers, which came to be known as “Ruperts,” were made from burlap and shaped like soldiers—but much shorter at just under three feet tall. A declassified American government paradummy testing video from May 1943 assured that “field tests have shown that the actual proportions of these dummies cannot be perceived by the enemy because of the absence of background, which allows for no standard of comparison.” To someone standing on the ground, therefore, the three-foot Ruperts were just as fearsome as a standard soldier.

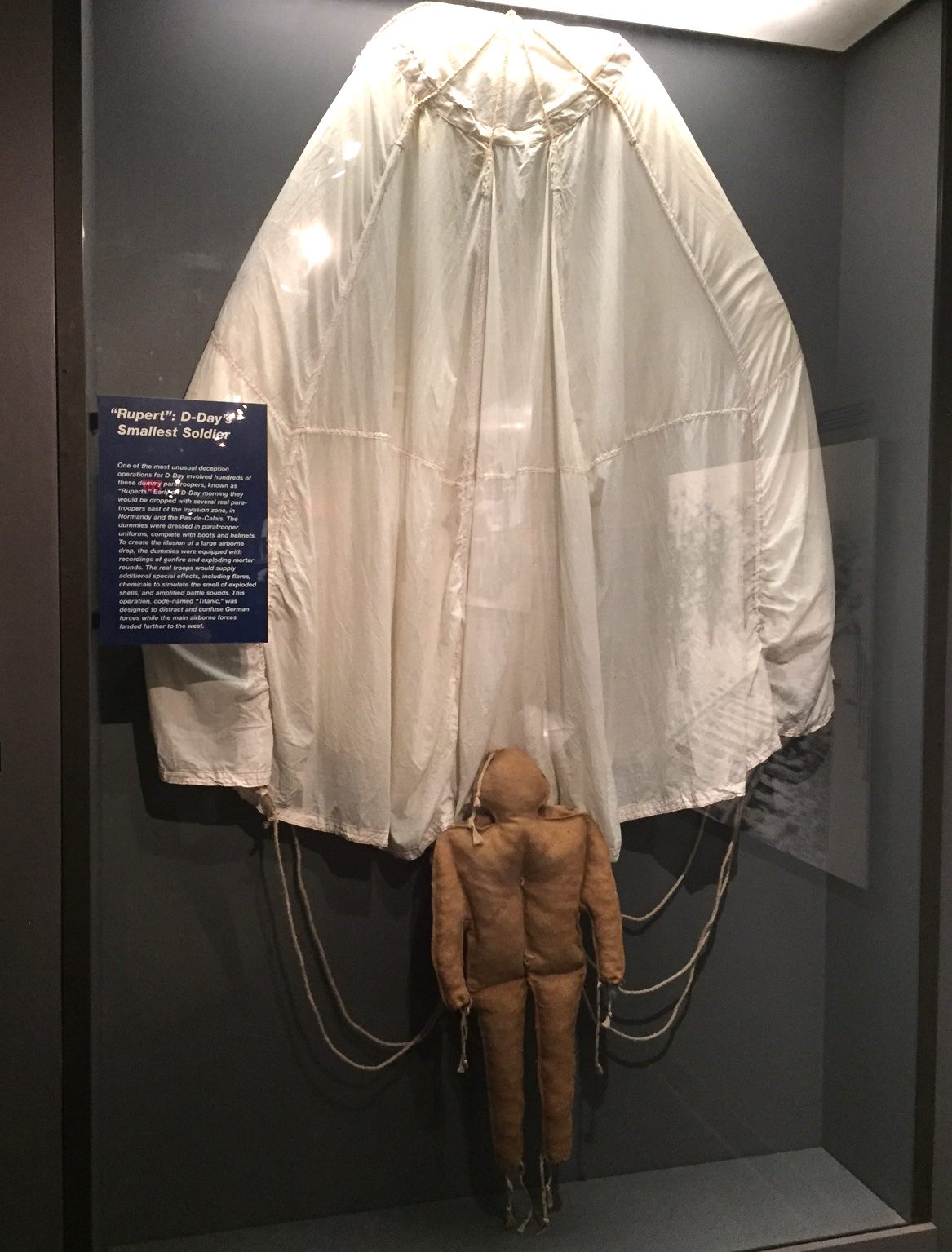

The full Rupert at the National WWII Museum. (Photo: Ella Morton)

According to a Rupert exhibit at the National World War II Museum, the D-Day dummies were dressed in paratrooper uniforms, including boots and helmets. In addition to the parachutes strapped to their burlap backs, each Rupert carried recordings of gunfire and exploding mortar rounds, to add to the authenticity of the simulated air attack. Drawstrings at the top of the head, wrists, and ankles allowed the dummy to be filled with straw or sand.

Operation Titanic kicked off late at night on June 5, 1944. There were three drop zones, all located north of the Seine. Two hundred dummies were dropped into the Yerville-Doudeville-Fauville-Yvetot area, 50 dummies landed around Maltot, and another 200 were dumped near Marigny. To ensure things went as planned, a team of human paratroopers from the British Special Air Service plummeted to the ground alongside their cloth counterparts. The real soldiers, says the WWII Museum, supplied “additional special effects, including flares, chemicals to simulate the smell of exploded shells, and amplified battle sounds.”

A Merville Bunker Museum exhibit showing the self-destroying Ruperts, which featured simulated rifle fire and explosives. (Photo: Pajx/Wikipedia)

When the Ruperts landed, they would self-destruct, exploding into pieces and leaving just a charred white parachute behind. Because of their explode-on-landing feature, few paradummies have survived as artifacts of Operation Titanic. They do, however, occasionally pop up for auction–in 2011, an unused Rupert sold for $3,346 at a Heritage Auctions sale.

To meet Rupert without having to make a bid, you can visit the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. In Normandy, there are also Ruperts on display at the Merville Bunker Museum, the Caen Memorial, and the Omaha Beach Memorial.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook